“Will you help me?” John Hancock remembers his neighbor Marcie Zambryski asking him in late 2022.

Hancock, the former director of the Spokane Symphony, has lived in Deep Creek Canyon since 2006. He and his partner Jane met Zambryski and her husband Larry a few years later and the two households became friendly. They are neighbors in the rural sense: a few homes sit between them, but they are about half a mile apart. The morning Zambryski asked for help, the two had just bumped into each other while Zambryski was on a walk and Hancock was checking the mail. It’s not uncommon to see your neighbors sporadically out here, and often only in passing, but Hancock realized this was the first time he had seen either of the Zambryskis in a really long time.

Zambryski told Hancock that Larry had died. A year later, her mother was gone as well, she told him.

“She spent a whole year grieving, not knowing what to do,” Hancock said, “and this was one of her first outings in the world.”

Both had succumbed to relatively rare diseases that may be caused by toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly called “forever chemicals,” because of how long they take to degrade in the environment. PFAS are a class of synthetic chemicals increasingly recognized to be associated with many health conditions, to include elevated cholesterol levels, changes in response to vaccinations and some cancers.

The Air Force later told Zambryski the contamination may have come from firefighting drills using a fire suppressant that contains several forms of PFAS.

Fairchild officials offered to install a filter on her well as part of a water program it runs to remediate the contamination, but Zambryski declined because she didn’t like the terms of the contract that she would have had to sign, which she says would require her to maintain the filter and heat the housing structure..

For the past six years, private well owners on the West Plains like Zambryski have had to navigate a patchwork of water-testing programs or pay to test their own wells for the chemicals, which can cost up to $400. Some buy or filter their own water. Others still don’t know whether they, their families, their pets and their livestock are drinking contaminated water.

Not long after Hancock and Zambryski bumped into each other on the road, they and a growing group of West Plains residents began advocating for a clearer pathway to clean water and more transparency about the depth and breadth of the contamination.

In the next few months — after over a year of pushing — more help will arrive.

Eastern Washington University (EWU) researchers and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials will start more systematically pulling water from West Plains wells and taps and testing it for PFAS.

The fruits of water activism on the West Plains

The West Plains Water Coalition (WPWC) was born in Hancock’s living room in December 2022, and has grown to hundreds of members — most of them residents of the West Plains. It gathers information about PFAS and the geology of the West Plains, which it publishes on its website, and hosts meetings so affected communities can hear from – and ask questions of – public officials and experts about the crisis. The coalition and several partners recently released a documentary about the PFAS crisis on the West Plains that was inspired by Zambryski’s story.

At a WPWC meeting last year, Dr. Catherine Karr, an epidemiologist in the School of Public Health at the University of Washington, told West Plains residents that the best response to PFAS exposure is to cut yourself off from the source of the chemicals. Doctors and scientists don’t know how to remove PFAS, which accumulates and doesn’t dissipate in the bloodstream of people and animals, nor do they know how to treat it.

The only way to limit the risk of a PFAS related disease is to stop drinking contaminated water.

But that’s hard on the West Plains, where private well owners do not have access to safe municipal water. Many have cattle, horses and pets. Many have gardens. Dozens of West Plains residents RANGE has spoken with over the last few months have done each of these things, but many feel underserved.

The new EPA program was announced at a meeting hosted by the WPWC at the HUB in Airway Heights Monday.

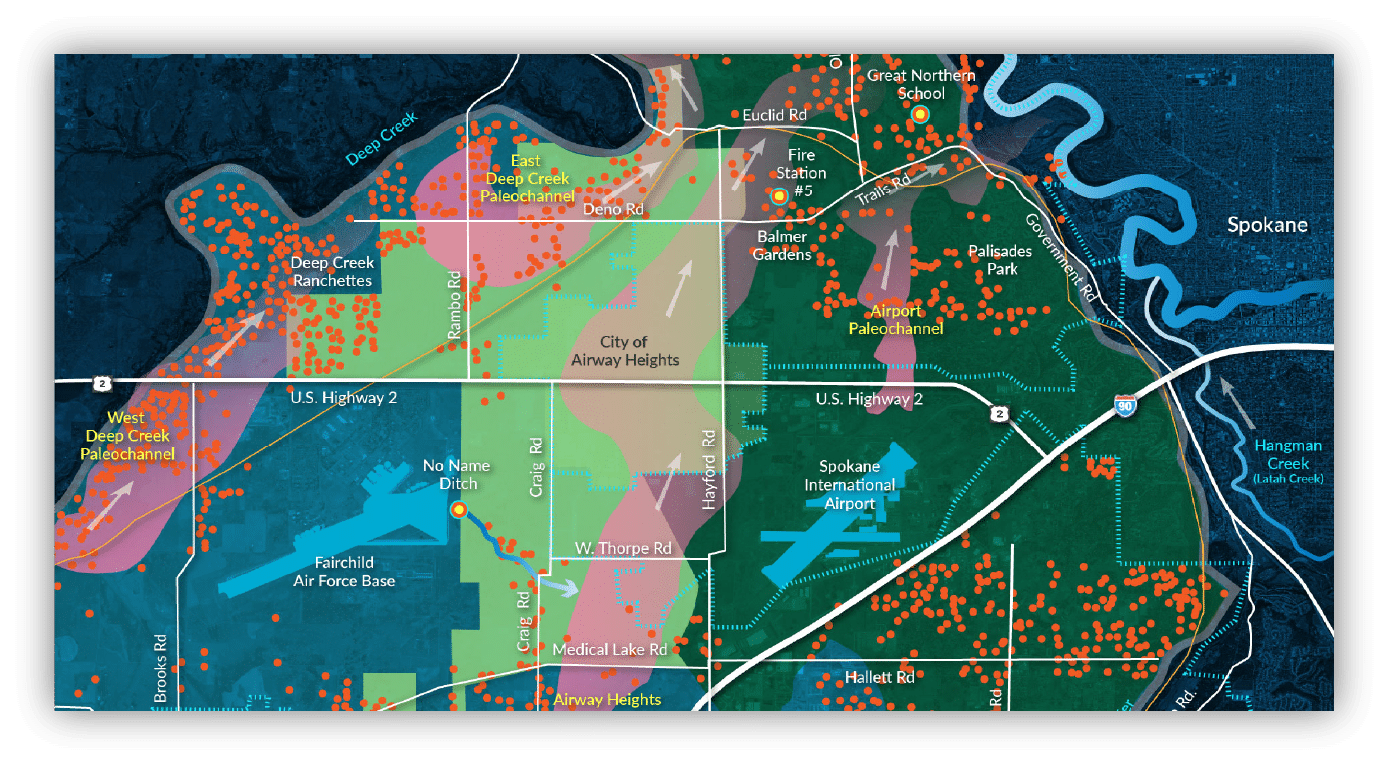

The program more than doubles the area currently served by Fairchild Air Force Base’s water provision program, extending much further north to the Spokane River and to the east, covering areas also potentially contaminated by a similar toxic spill at Spokane International Airport. In addition to the EPA’s work, Dr. Chad Pritchard, chair of EWU’s geology program, is spearheading a state-funded $450,000 study on West Plains hydrogeology that will map where PFAS are, and how they travel in the aquifers, which are slow-moving, underground bodies of water from which many communities in the area draw their drinking water. (The aquifers under the West Plains are not connected to the Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, which provides drinking water for Spokane and much of Eastern Washington.)

“We want to start sampling as soon as possible,” Laura Knudsen, a public involvement coordinator with the EPA, told a gathering of West Plains residents Monday night where the EPA program was announced. “We know this is critical. We know this is important.”

The source of the contamination is well known: forever chemicals are a key component in Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF), the best-known way to put out intense fires like those created by burning jet fuel. It’s rare for a plane to actually catch fire on the runway, but federal regulations require frequent emergency preparedness drills, and so, for decades, Fairchild and Spokane International conducted monthly drills, spraying large quantities of the foam onto the soil around each airport. From there it leached into the aquifers month after month, year after year.

Since the contamination was discovered in 2017, Fairchild ran a program to test wells and provide clean drinking water to residents of a small geographic area north and east of the base. But PFAS have been discovered in wells miles outside Fairchild’s program area. Anyone living outside that boundary is ineligible for the Air Force program. SIA has not started any programs at all, and didn’t tell the public or regulators of its contamination until last year, even though Airport officials and the board had known about it since 2017 and despite being required to report by state law since 2021.

EWU’s and EPA’s new testing programs have been a long time coming for residents of the West Plains. Because it is so deeply involved in with the community, the WPWC will help EPA interface with West Plains residents to conduct its testing.

A map, produced by the West Plains Water Coalition, showing Fairchild’s water program service area (in light green) and the underground water bodies that extend beyond it (shades of pink). Orange dots represent wells. EPA’s well testing program will roughly cover the dark green area of the map as a “Priority Sampling Area” because it’s outside Fairchild’s service area, and includes areas potentially contaminated by the same chemicals also used at Spokane International Airport. (Courtesy West Plains Water Coalition)

Other activists, some of whom started long before Hancock got involved, have been doggedly sleuthing documents through public records requests that exposed SIA’s contamination and painted a damning picture of SIA withholding that information from the public.

That’s how the Washington State Department of Ecology learned about SIA’s contamination and last year was able to force the airport to begin cleaning up. Erika Beresovoy, a public involvement coordinator with Ecology’s Spokane office, said that after Ecology became involved in SIA’s contamination, she and a Spokane team reached out to Knudson, Beresovoy’s EPA counterpart, to propose the testing program.

It’s possible that without the work of the WPWC and other activists, the EPA may never have stepped in.

Beresovoy hopes that property owners can start signing up in the near future.

“Our goal … is to publish an online form in the next few weeks where you can go in and answer a few simple questions, sign yourself up, and a sampling coordinator will contact you,” Beresovoy told people who attended Monday’s WPWC meeting. Anyone who has a private well in the sampling area can request a test. Sampling visits should take less than an hour, Beresovoy said, and test results will be sent to residents.

The WPWC will help distribute the form through its growing email listserv.

If you're a West Plains resident and you want to stay up-to-date as testing begins, sign up for the West Plains Water Coalition newsletter.

Studying where the poison is

Pritchard is a foremost expert in Inland Northwest geology and has researched the aquifers under the West Plains for years. The grant he won from Ecology, which is separate from the EPA program, will allow him to regularly test PFAS levels seasonally, recording fluctuations in the concentrations of PFAS through this year. Called a “fate and transport” study, the work will reveal how PFAS move through the complex of aquifers that lies under the West Plains.

Pritchard will sample 150 wells on a quarterly basis this year. The EPA well tests will also help provide data for his research, Beresovoy said during her announcement.

Pritchard had a harder time getting his hands on the $450,000 Ecology grant than he usually does with research funding.. Because the money had been allocated by the state legislature, it needed to be accepted and administered by a local government entity. As detailed by local investigative journalist Timothy Connor in his Substack Rhubarb Salon, public health and water officials advocated to the Board of Spokane County Commissioners that the county participate in the study, but the commission declined.

Records obtained by RANGE through a public records request confirm Connor’s reporting. They show the grant was awarded July 15, 2021. The Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD) was willing to be the local entity to administer the award, but because SRHD was not in the geology business, it would need technical help from Spokane County Water Resources, and the county would have to gather the data, according to emails between county and SRHD officials. That meant the Board of County Commissioners would have to accept the funds by vote at a commission meeting.

But the grant never appeared on a commission agenda. The money didn’t go anywhere for so long that Rob Lindsay, an Environmental Resource Manager for the county, told County CEO Scott Simmons in a September 2, 2021 email, that Ecology was starting to ask whether the county wanted the money.

“They are awaiting our response,” Lindsay wrote.

Simmons wrote back on September 8 that he’d discussed the grant with Al French, the county’s longest-serving commissioner: “I had a chance to discuss with Al yesterday,” Simmons wrote. “He indicated he would like to discuss further with the Airport prior to our committing to get involved. I’ll let you know more after I hear back from Al.”

At this point, the airport had known about the PFAS contamination for four years without disclosing it to the public.

On October 25, 2021, Pritchard emailed Mike Hermanson, a Spokane County water resources manager who had supported the grant and later left for a position at Avista, to find out about the state of the money. Hermanson forwarded Pritchard’s question to Lindsay. Hermanson, Lindsay and several others set up a meeting to talk about the funds.

The documents RANGE reviewed are unclear about what happened next, but Hermanson told RANGE last year that if the county had accepted the grant when it received it from Ecology, he’d likely still be working for it, rather than Avista.

Pritchard eventually surmised the money was just sitting somewhere in the state bureaucracy until 2022, when he heard the state still wanted to give the money to a local government on the West Plains that would accept it.

“That was really frustrating,” Pritchard told RANGE. “But I was surprised when I went to a meeting in 2022 and Ali Furmall, the Ecology grant coordinator for this grant, was like, ‘Oh, yeah, we still have the money.’”

So Pritchard brought the grant before the City of Medical Lake, and the city council there approved it. (Pritchard sits on the Medical Lake City Council, but he recused himself from the vote.)

He is currently drafting quality assurance protocols for his study and will begin his research in the spring, he told RANGE.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story said PFAS are known to cause certain diseases. While many health experts are recognizing an association between those diseases and PFAS, no definitive, causal link has been established. The story also said EPA would provide filters to West Plains residents whose wells test positive for PFAS. Ecology clarified that, while some agencies are investigating how to provide clean water to private well owners, and filters are one possible solution, the EPA has not established such a program.