Not long after they moved into a trailer home on a secluded property in the ponderosas between Spokane and Airway Heights in the early 2000s, Stephanie and Michael Mertell stopped drinking their well water.

Michael was having stomach pains he couldn’t fully explain, though he had an idea of the cause.

“He would claim over and over, ‘This water is making me sick,’” Stephanie said, speaking to RANGE in their living room, as Michael listened from his old recliner. They thought maybe high levels of phosphorus were causing Michael’s ailment.

The Mertells started hauling bottled drinking water into their home, and have done so since. But they used well water for other things.

“I cooked with it and made coffee with it,” Stephanie said. They also grew fruit trees, vegetables and herbs. “But then, when we heard about the chemicals, I quit making coffee with it.” They kept growing mint and basil, but not fruits and vegetables.

In December 2021, the Mertells received the first of what turned out to be quarterly letters from Fairchild Air Force Base. Fairchild lay upstream on Deep Creek, several miles southwest of their home.

The letters informed the Mertells that several forms of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, had contaminated their well — the result of firefighting drills at Fairchild. Similar operations occurred at bases across the United States from the 1970s until 2022, when firefighters, unaware of the toxicity, drenched soils with PFAS-containing foam designed to extinguish jet-fuel blazes. The chemicals then sank into the groundwater.

PFAS is the umbrella term for a family of about 14,000 water-resistant man-made compounds so persistent they’re known as “forever chemicals.” They are “increasingly recognized to be associated with many health conditions, to include elevated cholesterol levels, changes in response to vaccinations and some cancers,” former Spokane County Health Officer Bob Lutz told RANGE last year.

Only a few of those compounds were used to manufacture the AFFF, but those were considered among the most dangerous.

When the base first contacted the Mertells, PFAS were considered “emerging contaminants.” The federal government had not set limits for PFAS in drinking water. Meanwhile, internal research by manufacturers dating to the 1970s linked PFAS exposure to health problems in animals and humans, but they hid that information from regulators.

In 2017, the government was just catching up. Fairchild could only go by a “health advisory” issued by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — essentially a guideline, rather than a rule, that non-regulatory agencies can use to respond to contamination. It is usually in place while the EPA finalizes formal limits for any specific contaminant.

The level the EPA had identified for PFAS was 70 parts per trillion (ppt) — about the same as three-and-a-half water droplets in an Olympic swimming pool. That’s the metric Fairchild used to determine whether it owed the Mertells clean water.

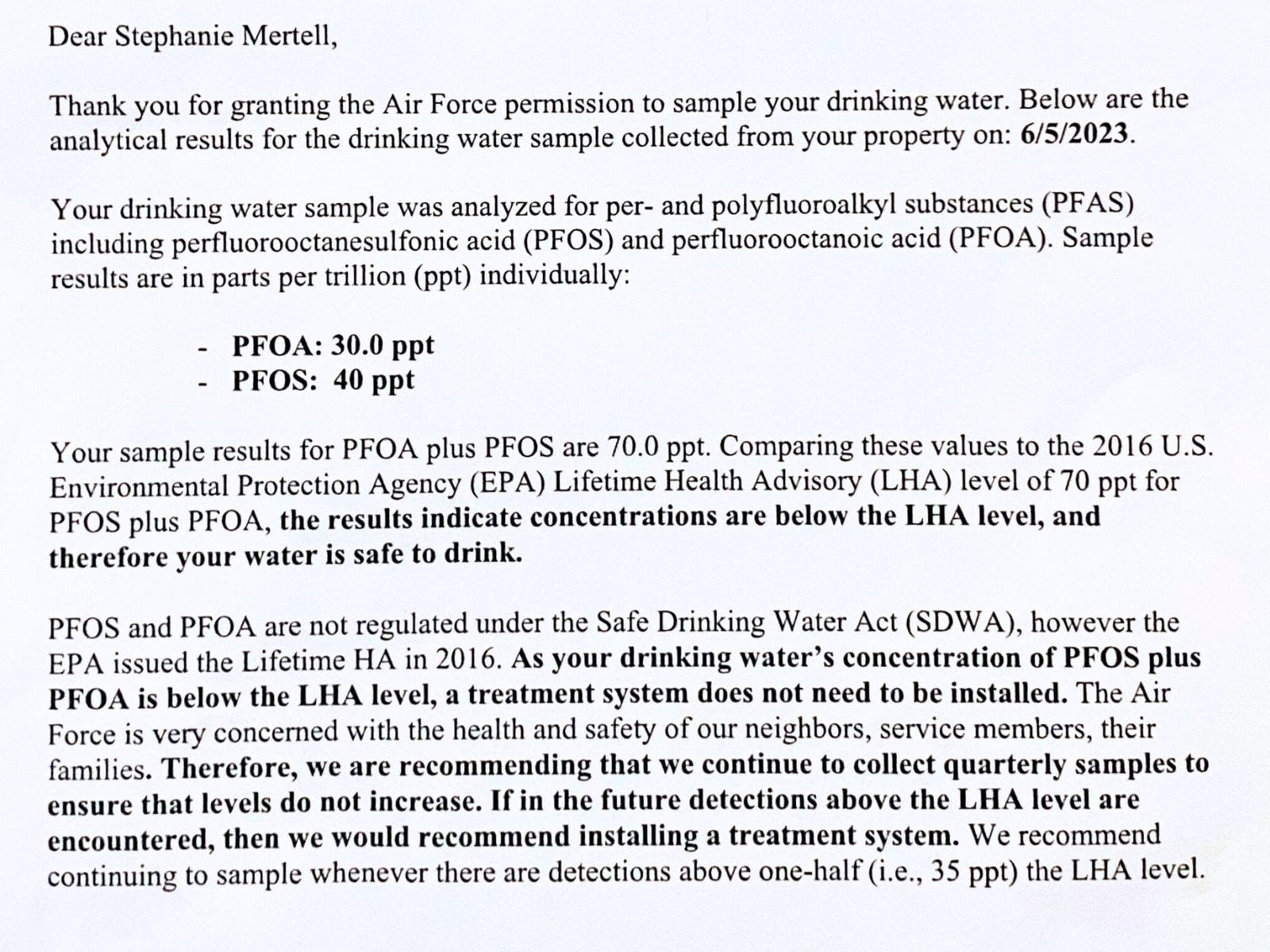

On May 6, 2022, Fairchild wrote in a letter to the couple: “Your sample results for [PFAS] are 57.0 ppt. Comparing these values to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Lifetime Health Advisory (LHA) level of 70 ppt … the results indicate that … your water is safe to drink [emphasis Fairchild’s].”

This level would not give them cancer or alter their organs, the letter implied.

In April, the EPA set a much lower health standard, this one a legally enforceable “Maximum Contaminant Level” (MCL) for PFAS: four parts per trillion, which is close to the smallest amount that can be measured using current technology. More than half of West Plains wells the EPA tested this spring exceed four ppt. Fairchild will now have to retest wells to determine current levels and will likely start providing water to many more people.

‘What EPA told everybody to do’

Through 2022, PFAS levels in the Mertells’ well increased. Fairchild sent a letter dated September 30 that recorded a level of 62.2 ppt. Again, they were told, “Your water is safe to drink.” A January 16, 2023 letter recorded 68.5 ppt. Then came another letter, reassuring the Mertells, “Your water is safe to drink.”

On February 20, 2023, the Air Force again tested the well, resulting in a measurement of 75 ppt.

After that reading, the base would have to provide the Mertells with clean water. A site inspector visited their home. But there were signs that a pipe was broken, so the Mertells would have to fix that before the filter could be installed.

“I'm bummed because I just shot myself in the foot,” she said. Stephanie told RANGE.

But the Mertells don’t care what the Air Force says or promises, and they didn’t trust their well water in the first place.

“Then, guess what? All of a sudden, I am filled with peace. Do you remember Choctaw Indians? My grandfather was a Choctaw Indian. They were the first tribe removed under the Indian Removal Act,” Stephanie, who is also a member of the Choctaw Nation, said. “And on the way from Mississippi to Oklahoma, in the middle of winter removal, they brought tainted blankets with smallpox and delivered spoiled meat.”

Stephanie said she didn’t want the government taking care of her in any way — she felt like she had dodged a bad relationship, saying having been denied a filter was “a blessing in disguise.”

On June 5, 2023, Fairchild tested again, this time finding PFAS at 70 ppt. Despite that, the Mertells were told, “Your water is safe to drink.”

In December, before the EPA codified the new limit, RANGE asked Fairchild if it thought 70 ppt was a safe level for drinking. Fairchild spokesperson Master Sergeant Jonathan Lovelady responded via email: “The Air Force follows DoD policy to provide alternate drinking water. … USEPA sets water quality standards and the Air Force adheres to them.”

The rules requiring use of PFAS-laden aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) are no longer in place, but only after decades of drills using huge amounts of AFFF, sometimes filling entire hangar bays with the foam.

Jon Welge is the civilian co-chair of Fairchild’s Restoration Advisory Board (RAB), a joint body of Air Force personnel and residents that provides a forum for the public to engage with the Air Force Civil Engineer Center (AFCEC), which administers environmental cleanups for the Air Force. He said the PFAS issue echoes environmental crises of the past, as regulators realized the toxicity of certain products after widespread damage had already occurred.

“That's what the EPA told everybody to do,” Welge said in an interview. “That's what we knew at the time. It's kind of like when we thought that asbestos was OK at two fibers per cubic centimeter. … Now, it's only safe at 0.5.”

The EPA’s new limit on PFAS is one in a series of developments across the country that have raised national awareness of the chemicals, prompting new urgency among regulators. States know they must invest in cleanup. Journalists are examining the extent to which manufacturers hid the dangers of PFAS. Organizations, like the National PFAS Project Lab, are advancing programs to promote awareness and solutions. In response, water utilities and corporations with a stake in PFAS manufacturing are suing over new regulations.

In this context, Fairchild — like Air Force bases across the country — is feeling pressure to move faster.

Plodding toward cleanup

The crisis on the West Plains blew up in the local news in 2017, when, after discovering PFAS in Airway Heights drinking water, Fairchild alerted the city and the Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD). Soon after, Spokane lawyers filed a class action lawsuit in federal court against the base alleging it used AFFF recklessly.

The base knew it would have to clean up the mess, but first it would have to do a “remedial investigation” to map the contamination. Progress is slow. Seven years later, research is still ongoing, and it will likely be years before it has a solid plan for a cleanup.

Meanwhile, Fairchild subsidizes a program in Airway Heights to pipe municipal water from Spokane to more than 8,000 residents. Private well owners were left out of this solution, so the Air Force began installing filters on wells with PFAS levels above 70 ppt or delivering bottled water to the owners.

At the February 7 RAB meeting, Mark Loucks, a civil engineer who oversees contamination responses at four Air Force bases around the West, including Fairchild, detailed the progress in a Powerpoint presentation on its filter program. Ninety filters had been installed. Four others had been connected to municipal water. Two filter installations were in the works. Two well owners had refused to sign the contract. Another was “no longer in communication with AF.” Two others had site conditions “prohibiting installation of a system.”

Hundreds of wells are still contaminated.

Pointing fingers

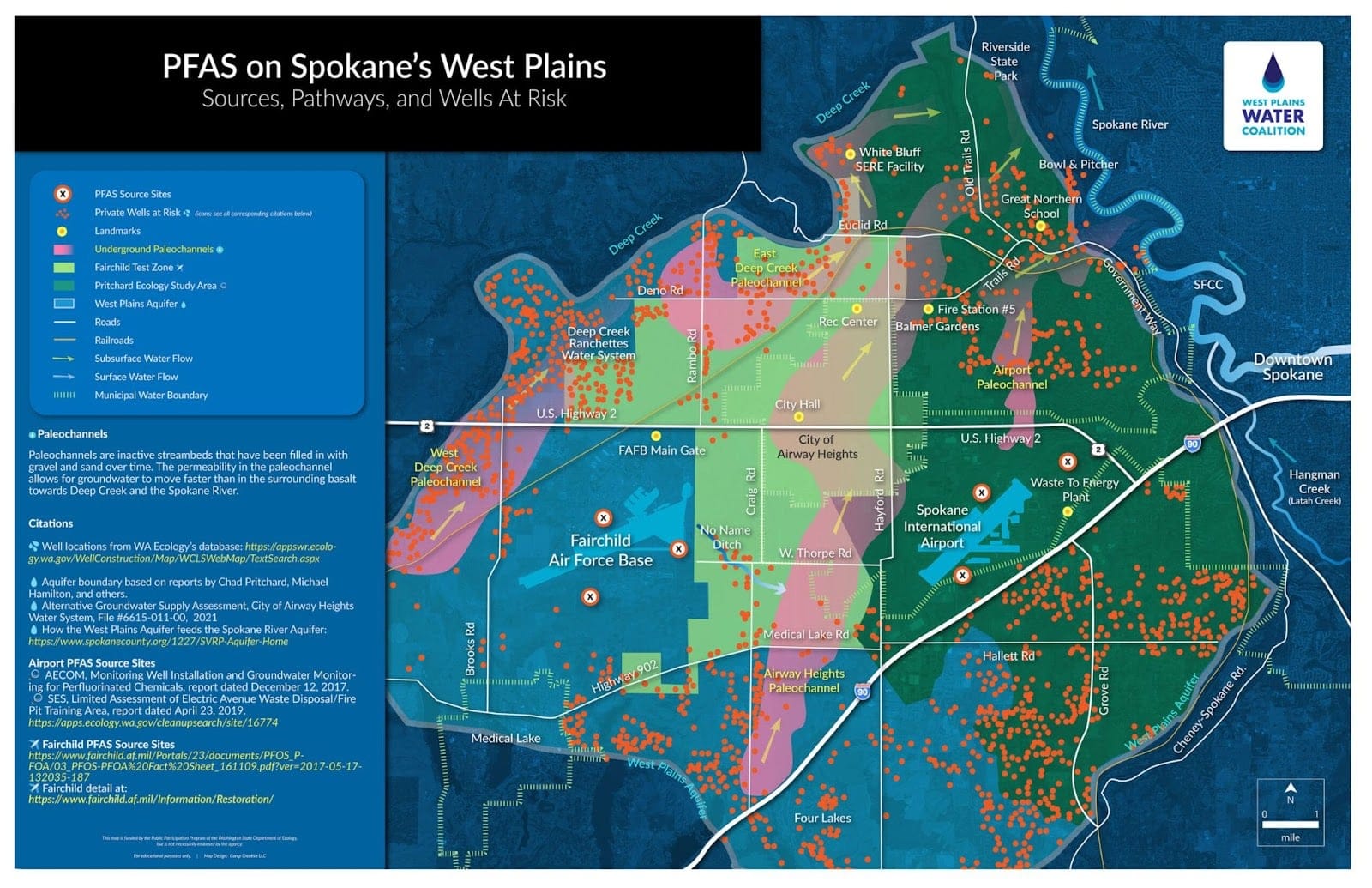

West Plains groundwater flows easily — carrying PFAS with it — along underground “paleochannels” scrubbed between basalt ridges by the Missoula Floods thousands of years ago. The base assumed its contamination was confined to the two paleochannels underneath it. Hayford Road runs roughly along the eastern border of the eastern-most paleochannel, so Fairchild used it as a boundary for testing. That meant any wells located between Hayford and Deep Creek — including the Mertells’ — were eligible for its water program.

Well owners east of Hayford — including hundreds who have found PFAS in their wells — were out of luck. Lovelady suggested contamination beyond Hayford was caused by Spokane International Airport (SIA).

He is right: as Fairchild was learning of its contamination, SIA also found PFAS in its wells from similar firefighting training. In contrast with Fairchild, SIA CEO Larry Krauter did not disclose the airport’s contamination until the airport was legally forced to do so in 2023 by a citizen’s public records request. The citizen gave the results to the Washington Department of Ecology in the spring of 2023. During the time he was silent about the contamination, Krauter lobbied lawmakers to allow airports to continue using PFAS AFFF. Ecology is forcing SIA to clean up its contamination through a state remediation law.

“Fairchild Air Force Base does not include the SIA site within its investigation,” Lovelady wrote in an email.

Chad Pritchard, an Eastern Washington University (EWU) geologist, has studied West Plains hydrogeology for years, most recently using a state grant to monitor PFAS in wells in a much larger area than Fairchild’s testing zone — going as far east as the Palisades, along the Spokane River. He said paleochannels are not the only conduits for PFAS.

“The other pathways besides paleochannels would be people that have drilled wells that have no lining in them. Those would also help communicate water,” Pritchard said. “Any of the groundwater that's in the basement or the lower basalt rock are all intercommunicating.”

Some of these factors potentially let contamination move farther east, outside of its testing area.

In an interview with RANGE, Loucks said the Air Force knows it may have to test wells outside the established service area, mentioning an area north of Fairchild that may be contaminated.

“We know that we're going to have to look there,” he said.

Filter rules

Some people served by Fairchild’s bottled water deliveries or carbon filters are also unhappy. Marcie Zambryski lives down the road from the Mertells. In 2021, when her husband Larry was diagnosed with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer, she didn’t know about the contamination in her well.

“His cancer was so involved at that point,” she said. “It was up in his throat, both sides of his neck here, and the whole body of the pancreas was cancer, and then the main veins around it were encased in cancer. His adrenal glands had cancer and that pushes through your whole body.”

Sitting at her dining table, she pulled out a document dated February 1, 2022.

“Six months after he passed away, I got that letter in the mail with a pamphlet on PFAS, and I'm like, ‘Why did you send me this?’” Zambryski said.

Her mother, Shirley Morgan, died not long after, of a rare form of breast cancer. Two of her five boxers also died of cancer. Zambryski worries that vegetables she grew using water from her well and fed to her grandchildren are causing them health problems.

Fairchild offered to install a granulated carbon filter on her well, but it requires her to sign a contract with conditions she does not want to accept, including notifying the Air Force if someone else moves onto her property.

Fairchild brings her 15 three-and-a-half-gallon bottles of water that feed into a dispenser every other Wednesday.

She wants to sell her home and move but doesn’t see how that will be possible with the contamination.

“What am I going to say?” she said. “House for sale, toxic water, 183.5 parts per trillion. … No one's going to want to buy this house.”

Months to ink contracts

For some, Fairchild’s actions are agonizingly slow. The base hosted a listening session on April 24 at the El Katif Shriners Center, two weeks after the EPA had codified the new “Maximum Contaminant Level” (MCL). During a Q&A, a woman who said her well feeds dozens of West Plains homes pointed out that the EPA had announced it would create the new level months before that meeting. She said Fairchild should have been ready to start installing filters immediately.

“You should have had plans in place on April 11 to start distributing drinking water, to start testing additional wells, to start handing out faucet filtration systems,” the woman said. “It's so frustrating at this point. … I didn't cause this. The Air Force did. When are you going to do something?”

Loucks, who was part of a panel of RAB and Air Force officials, responded, “There is a program being put together. I wish I could say that it was ready to go right now.”

“It's been seven years,” the woman said. “This didn't happen last week. … We have so many people who have lost their entire livelihoods.”

Loucks called on his boss, Ravi Ravichandran, the lead PFAS response official for the Air Force's civil engineers. Ravichandran got up from his folding chair in a corner of the auditorium and explained to the woman that the problem was bigger than Fairchild. Hundreds of Air Force bases had caused similar contamination, and its remediation could not happen at every base, all at once.

“We cannot install a system … at every place all at the same time,” Ravichandran said. “We like to prioritize based on concentration. Highest concentration gets treated first.”

He said it would be months before the Air Force could contract with private companies to install new filters around Fairchild. Even then, Fairchild would have to retest the wells for current PFAS levels.

“So it's not that we haven't done anything,” Ravichandran said. “But we cannot spend a dollar until the [new maximum contaminant level] becomes final.” After the level is codified, it takes time to mint contracts and get filter programs off the ground.

The woman was not satisfied.

“It's been 14 days” since the new MCL went into effect, she said. “You've had data, as far as hundreds of wells in our area alone, that are below the 70, but above the four. How many filtration systems have you installed in the last 14 days? … This is people's lives.”

Systemic limitations

Fairchild is in the business of sending military planes into the sky, not providing water to its neighbors. Its leadership is constantly in flux with a commanding officer who changes every two years, which is how military commands across the country rotate their commanders.

“The commander is there for the mission of the base,” said John Hancock, a West Plains resident and water activist. “And that doesn't include the neighbors. That's talking of the world, saving the world. … So the local frustrations and dangers and affronts are not very important.”

Like any military base, Fairchild is bound by strictures dictated by the Department of Defense and a tangle of other federal agencies that restrict its ability to respond to the environmental crises it might cause or contribute to.

“The Air Force has a narrow scope of authority on when and what types of actions can be taken regarding PFAS,” Lovelady wrote. “This has been communicated through the RAB … to enhance awareness of this fact.”

Fairchild follows an environmental contamination management manual requiring all bases to clean up in a way that doesn’t interfere with operations. They must “ensure uninterrupted access to the air, land and water assets needed to conduct the AF mission,” the manual’s introduction says.

But all these limitations are cold comfort to a community that has poison in its water and feels iced out by the bureaucracy.

In late 2022, Hancock founded the West Plains Water Coalition (WPWC), which advocates for solutions to the PFAS crisis in the region. The organization holds frequent informational meetings at the HUB in Airway Heights, inviting speakers from the Washington Department of Health, EPA, EWU, the Spokane County Board of Commissioners, SRHD and other organizations. At the most recent meeting on June 3, Hancock said he had invited Faichild and SIA to speak. Fairchild declined; SIA didn’t respond.

He said Fairchild doesn’t exert a stronger presence in the community partly because AFCEC — the Air Force civil engineer arm that responds to environmental crises and does not do public relations as part of its mission — is administering the water program.

“It's all gravel and water and pumps and tests,” Hancock said. “It's not a human services organization, as I think it should be. These are humans with trouble.”

Asked whether Fairchild feels like it’s part of the local community, Lovelady wrote in an email to RANGE: “Certainly!” he noted 1,400 airmen and 5,000 family members live on base and in the surrounding area.

“Protecting the health of our personnel, their families and the communities in which we serve is a priority for the Department of Air Force,” he wrote “Fairchild Air Force Base takes great pride in being part of the INW community.”