The Trek to TRAC

A street photographer walks 3.9 miles in the shoes of those searching for shelter during the summer heat wave.

BY ERIN SELLERS ● ENVIRONMENT ● AUGUST 17, 2023

If it weren’t for the constant noisy trundle of trucks speeding past, the industrial wasteland that sprawls out along East Trent Avenue could be the setting of a Spaghetti Western — a cliche, complete with scrubby sagebrush and a sadistic sun that beats down relentlessly.

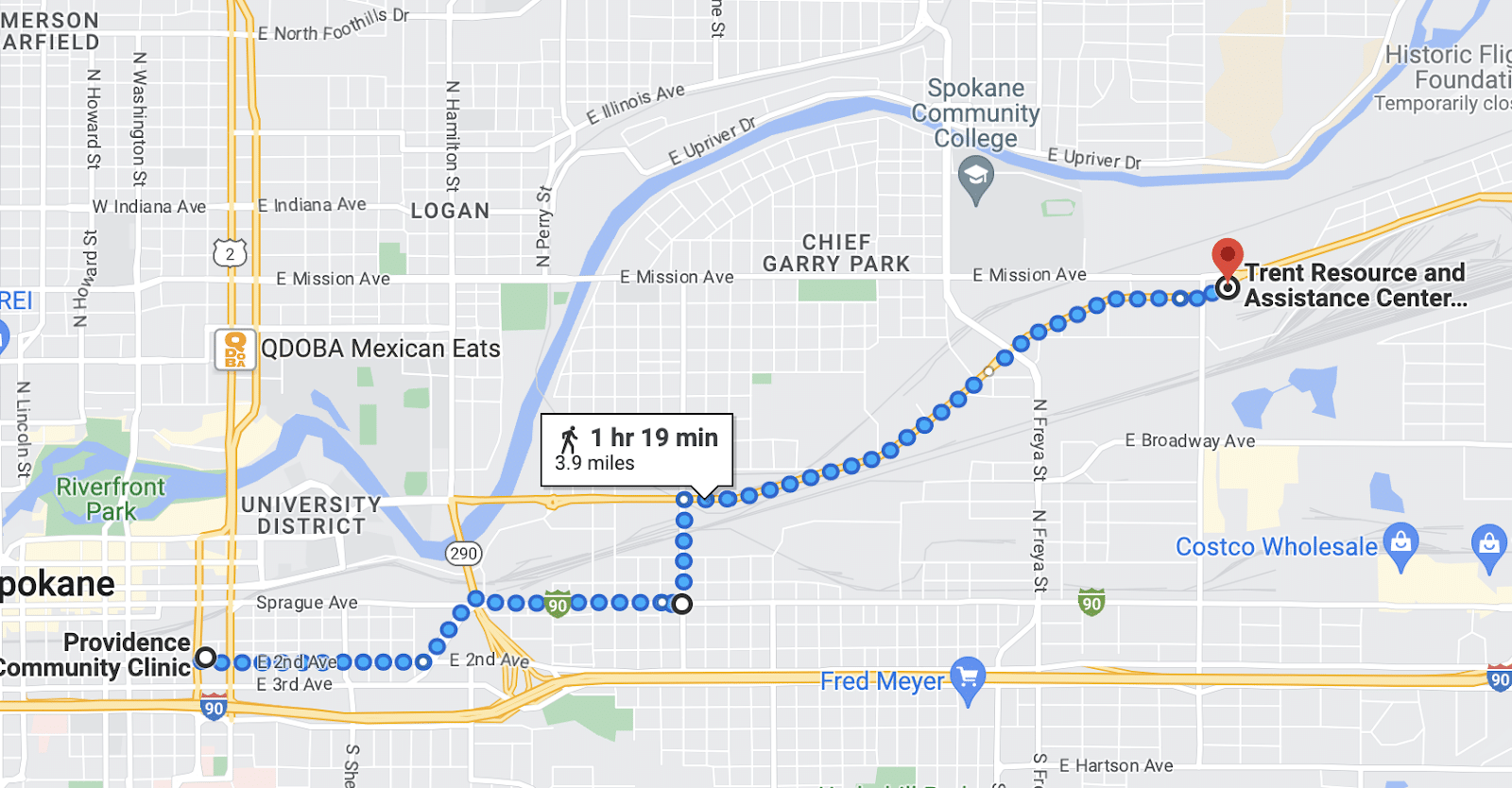

This Tuesday morning it is so hot, my phone gives a heat advisory for travel at 10:30 am. That’s when Ben Tobin, with this RANGE reporter in tow, begins his trek from the Providence Community Clinic downtown to the Trent Resource and Assistance Center (TRAC), the city’s newest and largest homeless shelter in an industrial converted warehouse.

The journey is many things, a challenge to those involved in the politics of homelessness, a test of human endurance, even an exercise of privilege, as Tobin acknowledges, sharing that he is starting off with a “clean bill of health and a full night’s sleep,” and that he “was lucky to be able to come home to 75 degrees, water and place to sit down.” Ultimately, the 3.9 mile walk in record-breaking heat, which brought asphalt temperatures to 123℉, is a continuation of Tobin’s six years as a street photographer focused on capturing Spokane with a distinctive visual realism and boots-on-the-ground empathy.

Before we set off from the Community Clinic, Tobin says hello to a few homeless folks he recognized and has a lengthy conversation with representatives from Jewels Helping Hands, who are running pop-up showers and passing out resources to help with the heat downtown. Ken Crary of Jewels Helping Hands gave us what he thought was the best route to TRAC, and offered us supplies for our journey.

There is a matter-of-factness about Tobin, a confidence in the way he carries himself, navigating easily through downtown Spokane, striking up conversations as he goes.

The first leg of the journey proves the easiest, and the most familiar. The walk is shaded by the buildings and elevated train line that separate Downtown from the University District. As he strolls, Tobin talks about his time in the nineties working as a bike messenger in Seattle, art school and his father’s struggles with mental health issues. These experiences nurtured Tobin’s empathy for people on the street, which grew over time into a dedication to get to know and, with their permission, document the individual faces, hands and hearts that are often aggregated and abstracted down to statistics, stereotypes and sob stories.

“These people are no different than you and I,” Tobin says, emerging from under the tracks at Division and Sprague into the glare of the morning sun. “We need to talk to them like they’re our friends or someone we know.”

As he describes the way that homeless people are made invisible in our society, his voice and hands get more animated. “Imagine going to the grocery store every day, and every time you give someone eye contact, they just look down at the ground,” he says without breaking stride. “That would eat at you. I bet you if you did that for a week, you would fall apart in tears.”

So Ben Tobin seeks to see the people who are ignored. He talks to them. He meets them where they’re at — asking questions about how they’re doing or what their background is. He becomes a part of their community, walking the same streets around Carnegie Square on First Ave nearly every week. When the people he meets give him permission, he takes their pictures.

Tobin got his start as a street photographer in an unconventional place. A professional photographer for close to 18 years, shooting everything from professional mountain bikers to corporate marginalia for Avista to bucolic landscapes and lively street scenes for Washington Tourism and Visit Spokane. He worked for the Seahawks. He’s been published in National Geographic.

It wasn’t until about 6 years ago, though, that he began to develop his particular eye for the way people and space intermingle in Spokane. Leaving the pubs downtown, he saw something specific and beautiful in the lines of the skywalks and wanted to capture them. When he got sober, following a traumatic brain injury, he finally gave chase to that desire.

At the same time, Tobin’s father was going through serious mental health issues (issues that remain unresolved). And so, downtown one day with his camera in hand, Tobin found himself in conversation with a homeless man whose life and story wasn’t so different from Ben’s own. That conversation led him to turn an Instagram account he had used mostly for action sports into his ongoing narrative of Spokane.

“It’s awkward walking up to someone who doesn’t have a home to go home to, and asking how their day is going,” Tobin wrote in the caption of a recent Instagram post of a shirtless man sitting cross-legged on a sleeping bag and grinning into the camera. “But I firmly believe it is important to do. You have no idea how powerful the act of conversation can be to another person.”

Tobin remembers one man he met who, after a life of working in the restaurant industry in Idaho, had no retirement plan and found himself on the streets of Spokane. Talking with the man, he didn’t see a life in ruin, but a life of almost superhuman endurance.

“It’s literally like going and seeing someone that just crossed the finish line of a marathon. You’re like, ‘Dude, you just keep freaking going. Holy hell, you are amazing,’” Tobin said, somehow still full of energy. “And how unfortunate it is that others don’t just walk by you and high five you like, man, you’re a badass.”

This is how Tobin documented the people of Camp Hope — by spending time with them. He estimates he visited the encampment a dozen times, and spent hours on each visit learning what he could about the people who called it their home. He speaks about the unifying simplicity of the basic human needs we all share — shelter and community — and how the folks he met at Camp Hope are struggling to regain that basic connection now the camp has been disbanded.

He has re-discovered many of the people who were pushed out of Camp Hope while biking through the natural areas that run along the river and connect up into Rimrock, Palisades and Indian Canyon. They have not found family, permanent homes, or a safe place to shelter. They’ve been pushed into the hinterlands by camping ordinances and park closures, away from centralized resources and community. With an even more restrictive camping ordinance set to appear on the ballot in November, and what he sees as an increased politicization of homelessness with no effective and compassionate solutions from local government, Tobin said he feels things can only get worse for them.

1.2 miles into the journey, Tobin stops outside Nuestras Raices Centro Comunitario. Here, he sips from his insulated water bottle and snaps a photo of the center’s cooler, the first and last free water that will be available on the route — unless you count the bubbling decorative fountain outside the descriptively named Spokane Pump.

Somehow, despite the oppressive heat and his unrelenting pace, Tobin maintains a steady stream of thoughts, bouncing back and forth between his opinions on politics, his career trajectory, and his brother’s empathy-refining advice: “You ever want to learn about how selfish you are? Get married and have three boys. Every time you think you’re owed something, a few seconds later ‘fool!’ comes to mind.”

As we turn off Sprague and onto Napa, Tobin begins to talk about the ethics of his artistry. He knows the critiques of street photography as sensationalizing or objectifying subjects; it’s something he discussed with his girlfriend recently while she passed out sandwiches to folks alongside him on his weekly photography route. He says ultimately his answer is in intention and consent. First, he gets to know a person. Only after that, and only if the vibe is right, he asks to take their picture.

“The only time I take a photo of somebody without their permission is when they’re passed out on the sidewalk … and most of those people I see on the ground, I have actually asked them at one time if I could take their photo,” he says. “I take these photos because my intentions are ‘People need to see this.’ People need to see this on a daily basis. I’m making people see the folks that they’ve been trying to pretend are invisible.”

Tobin’s goal isn’t to objectify or alienate, but to build community through his camera, and through the conversations he has both on the streets and off. His photography is his way of approaching the “problem” from his lens as an artist.

“I believe in this,” Tobin said. “And the people I’m having conversations with, these are people that I believe in, they’re people that I want the best for.”

He mentions that his photography brings him a lot of hope, helping him cross political and ideological lines with his audience, including a neighbor in the West Hills who vehemently disagrees with him.

“If it’s artistically shot, it gives them some breathing room to just question what’s going on and I think people just need room to breathe before making up their mind about something. We all do,” Tobin says.

And that’s what the journey to TRAC was about — an exercise in empathy. While some of his Twitter followers originally thought it was performance art, it’s more about experiencing what someone would have to go through to find respite.

When we hit the halfway point, cresting up Napa and onto Trent, we’re confronted with an industrial sprawl so hot, the heatwaves roll up from the ground and bend the sunlight into mirages. Deadly, but also cartoonish.

There’s no shade to be found. No restaurants or public spaces to rest in. And, not far down Trent even the sidewalks disappear, giving way to a dusty, gravely scree. The entire journey is difficult. This section is all but impassable for anyone in a wheelchair. This point in particular frustrates Tobin, who went to school for industrial design and took courses in “the human factor.”

Whether it’s the people on the outskirts of Spokane, residents of downtown, or unhoused folks, the ability to use our roads and sidewalks is vital for everyone, and it’s here that Tobin thinks there’s an opportunity for unity between our fractious political forces.

“We’re a village,” Tobin says, a sentiment he repeated multiple times during the journey. He thinks we should act like one, taking care of everyone in our community.

At about Trent and Freya, Tobin’s stamina finally began to flag. The conversation slowed. The bleach-white UV rays beat down on us from above while heat radiating up from the asphalt pushed through the soles of our shoes and sunk into our calves. There is nowhere to drink water, nowhere to sit, nowhere to rest.

Occasionally the sidewalk reappears briefly. Sometimes you have to run across the four-lane road, jumping curbs to get to it. The traffic is head-splittingly loud and whizzing by at a distance that is far too close for comfort. We pass two coffee stands, Vien Dong Restaurant, and the Oriental Market. “You know what sucks?” Tobin asks. Surprisingly, it’s not the temperature. He’s circling back to our conversation on the rules of his photography. “I see something clear as day, but the restrictions of this game are, I don’t get to use words.”

He doesn’t need to. His photos speak for themselves.

Finally, after what feels like a never-ending slog down Trent, Tobin breaks down and checks his phone to ensure we didn’t overshoot TRAC. There’s an excessive heat warning, but we’re almost there.

The last fifteen minutes are misery, ignoring the sweat that is somehow everywhere, trying to focus on putting one foot in front of the other. The sidewalk returns long enough to accommodate a bus stop. Tobin nods at a woman in a powerchair waiting for her bus. And then, almost anticlimactically, a shabby beige building with a nondescript sign signals our destination. TRAC. Tobin has reached Ithaca at the end of his Odyssey.

We stand outside for a few minutes, then Tobin goes in to see how the air feels. He’s greeted by shelter staff and a GoJoe security guard. They try to check him in, but when he tells them he’s just stopping to rest for a second, they grab him water.

There are between 40 and 60 people inside the shelter, many of them grabbing free food being handed out just past the check-in point. Four large Portacool swamp cooler fans with ice in them hum in the background, and though the stubby, cubicle-like partitions offer just as little respite from the glare of the warehouse lights and the dozens of eyes as the industrial landscape outside does from the glare of the sun, at least it is much cooler in here.

People come and go. A chihuahua in a diaper drags its owner down a hall.

Though the conditions at the shelter are better than he expected them to be, Tobin is still frustrated by the lengths it takes to get here. The walk was arduous for him and would be impossible for others. The bus system out this far is intermittent and complicated to navigate, requiring a transfer between lines, which can leave folks sitting outside at the unsheltered stop for long periods of time waiting to be picked up.

“Dogs get a better ride to SCRAPS,” Tobin mutters. “At least they get picked up, and the intentions are to get them to a home.”

Then, it’s time to go back. We walk back to the bus station, where the woman we passed about twenty minutes earlier is still waiting for the bus. Tobin offers her a sandwich he picked up from Jewels Helping Hands, but she thanks him and declines.

She says she’d rather have a fan.