Post-publication editor’s note: The Strippers' Bill of Rights was signed into law by Governor Jay Inslee on March 25. The full bill can be read in its entirety here.

Content warning: The beginning of this article includes a description of a sexual assault which may be distressing or triggering for trauma survivors. If you would like to skip past this part, click here.

Ashe Ryder and her coworker followed their male client up the steps into the VIP dance room at the now-shuttered Deja Vu strip club in Spokane Valley. Thick, black curtains and low lighting in the space created the "dark and mysterious" mood that Ryder said helped conjure the fantasy of intimacy for the men who paid to be there.

He was their first client of the night on an evening in early 2023. They had both expected to provide him with the typical 15-minute private dance that made up the majority of their income — paying between $125 and $500 per session, depending on dancers' personal rates and the cut taken by the club. Those dances could pay their bills.

They could also be risky.

Because Washington state regulations currently don’t allow for the sale of alcohol at strip clubs, patrons often arrive already intoxicated, leading to handsy, inappropriate and sometimes aggressive behavior toward dancers.

“They tend to go to a bar next door and get way too drunk way too quickly,” Ryder said. “They’re trying to maintain a buzz while they’re inside of the club, so they’ll do like four or five shots and a couple mixed drinks or a beer before they even come in.”

That was the case with the man who asked Ryder and her coworker for a 15-minute private dance in that dim-lit VIP room, a transaction in which Ryder expected to make more than $200. Her coworker asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

Just as they drew the curtains, the man got aggressive. He grabbed the other dancer by the clavicle and yanked her toward him. As Ryder tried to pull the man off her coworker, he grabbed her, too.

“He pulled my panties down and attempted to penetrate me with his fingers,” she said.

Ryder shoved the man away, and she and her coworker ran to the bouncer and manager for help. Ryder said they confronted the man and kicked him out of the club, but he refused to pay either dancer, telling their manager, “They didn’t even do anything, so I don’t need to pay them!” Ryder and her coworker tried to confront the man for their money, but said their manager stopped them from following him, though Ryder’s coworker was able to snap a quick picture of his license plate as he peeled out of the parking lot.

State law prohibits dancers from accepting upfront payment for their performances; which, according to Ryder, leads to a “lot of theft of services” — an offense for which you can call the police.

So she did.

When deputies from the Spokane County Sheriff’s Department arrived, Ryder was sitting on the ground in the lobby crying. As she tried to report the man’s assault and theft of her services, she said the officers asked her three questions:

“What were you wearing?”; “Were your panties even on?”; and, “Were you soliciting prostitution?”

Ryder said the deputies concluded the interview by telling the two dancers they could press charges, but it was unlikely they would go anywhere because there was no evidence of what happened. Still, the dancers provided the deputies with a description of the man and the car he’d been driving.

Ryder said she found out later — not from anyone in the Sheriff’s Department, but a friend of a friend at the Spokane Police who checked arrest logs — that the man had been arrested later that evening for driving under the influence and driving with an expired license, but not for what he did to Ryder and her coworker.

“After that experience, anytime something like that happened to me, I just stopped calling the cops,” Ryder said. “Every time they came, they never helped.”

Spokane County Sheriff’s Public Information Officer Corporal Mark Gregory did not return multiple requests for comment on this story.

RANGE heard similar sentiments from multiple dancers. They didn't feel safe or protected by the legal system and faced stigma whenever they tried to report violence against them.

Advocates for the group Strippers Are Workers (SAW) say stories like Ryder’s are too common and, from their perspective, are a direct result of the working conditions in Washington strip clubs, created by strict regulation of the clubs by state codes.

Ryder, who is a member of SAW, has danced in other states, and believes the regulatory framework in Washington puts workers at risk.

“Unfortunately, it's a regular occurrence in Washington,” Ryder said. “In the six years I've been dancing in Portland [Oregon], that's only happened to me once.”

Now, after a yearslong effort, a bill that would codify protections for dancers has passed both the House and Senate and is close to becoming law. Ryder hopes it would give all dancers in Washington a better working environment, and make experiences like the one she had that night much less common.

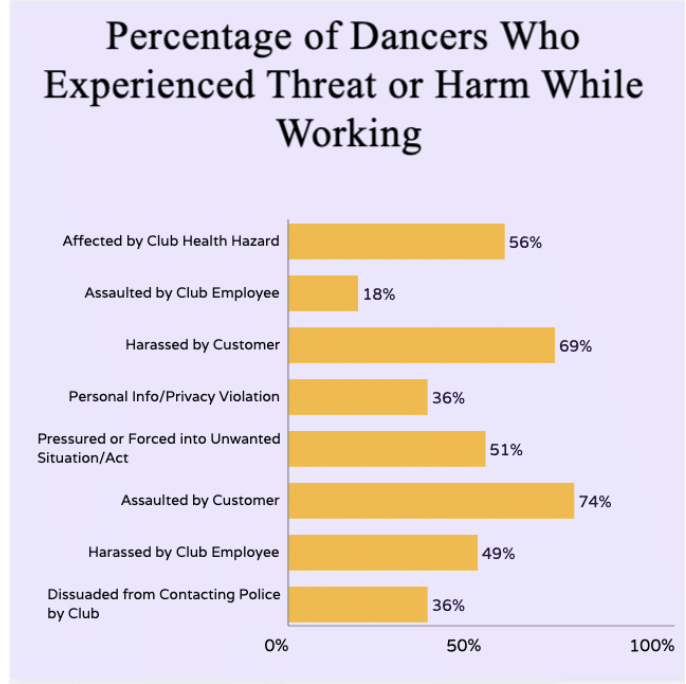

Statistics from a survey put out by SAW show 74% of Washington dancers have been assaulted by a customer, and 36% of them dissuaded from contacting police by the club they danced at.

Strip clubs in Washington operate on a tenuous profit model — because alcohol sales are forbidden, clubs instead make the majority of their money off of dancers by requiring them to pay club fees of $150 to $200 per night for their stage time. It’s a similar model to tattoo artists renting their booth from a tattoo parlor or hair stylists renting their chair from a salon, and treating the service providers as independent contractors instead of employees. Clubs don’t pay dancers to perform. Instead, dancers pay clubs for their stage time, and the clubs also take a cut of their earnings on private and VIP dances.

At Deja Vu, where Ryder danced, the club minimum had been $125 for a private dance, with the club taking a $25 cut. In May of 2023, those rates changed. The club minimum went up to $200, and the club started taking $75. When that change happened, Ryder stopped selling rooms altogether: “The cut was dipping too much into my earnings, especially for local customers to afford.”

Stage rent is a common practice in other states, too, but dancers say that compared to Oregon, the clubs in Washington charge extremely high, predatory rates. And, even though they’re classified as “independent contractors,” with control over their own schedules, if they call in sick or otherwise cancel their scheduled stage time, they still have to pay those stage fees for what management calls “back rent.”

This essentially indentures dancers to the clubs at which they perform.

“You’re independent contractors, and you’re paying super-fucking-high fees to work,” said Madison Zack-Wu, a dancer from western Washington who serves as campaign manager for SAW. “You can owe money at the end of the night.”

On the night Ryder was assaulted, after taking a short break to compose herself, she went back out onto the floor to finish her shift — because she hadn’t been paid for the private dance cut short by violence, she hadn’t made any money yet.

Her club had stopped the practice of back rent when COVID-19 restrictions lifted and it reopened, but if the incident had occurred before the pandemic, she could have owed the club money for that evening, had she chosen to go home.

The law of stripping

Zack-Wu and Ryder have been major advocates for Senate Bill 6105, sponsored by Sen. Rebecca Saldaña (D-Seattle) and lovingly referred to by the dancers as “The Strippers’ Bill of Rights.”

The bill, which seeks to create safer working conditions for dancers, has now passed both the Senate and the House. The last step is for it to pass a concurrence vote in the Senate to approve amendments made to the House version. It’s likely the bill will end up on Governor Jay Inslee’s desk for signature early next week.

“Strippers are doing work. They're workers and so they deserve workers’ rights,” Zack-Wu said. “They've been historically marginalized and denied fundamental rights.”

If the bill clears these final hurdles in the legislative process, it will be a victory over five years in the making for the members of SAW, who began their fight in 2018. An earlier version of the bill died in the House in 2023 after passing through the Senate.

The main points of the bill focus on protecting workers, rather than punishing abusive clients(although it would require clubs to maintain blacklists of those abusive clients), and might result in higher revenues for club owners as well.

The bill:

- Requires the Liquor and Cannabis Board (LCB) to repeal WAC 314-11-050, creating a pathway for clubs to apply for liquor permits.

- Prohibits back rent practices.

- Caps dancer stage fees at $150, or 30% of the dancer’s earnings for that day, whichever is less.

The rationale for allowing clubs to sell their own alcohol is three fold: it would disincentivize patrons from binge drinking before entering, allow bartenders to better track patron consumption and give club owners an additional revenue stream that make up for the revenue lost by the fee caps and prohibitions on back rent.

The law would also codify explicit safety protections, including requiring panic buttons in private rooms — which could prevent situations like what happened to Ryder — establishing anti-discrimination protections for dancers, requiring minimum security staffing in clubs and creating mandatory sexual assault/harrassment training for all club employees.

For the first few weeks of the legislative session, the fate of the bill seemed murky: after all, it had failed the year before. In early February, though, police in Seattle drew criticism for a series of raids on gay bars where officials determined that certain styles of dress constituted “lewd conduct” violations, which protestors alleged functioned simply to criminalize queerness, rather than actually uphold the law. Because of the quick public outcry— the bill saw a boost in support, with lawmakers finally starting to rally behind the legislation, which would also direct the LCB to change lewd conduct rules.

Because the Strippers' Rights Bill would direct the LCB to change those lewd conduct rules, SAW connected with prominent west side 2SLGBTQIA+ community members sex columnist (ed. note: and John Cameron Mitchell character) Dan Savage and Joey Burgess — the latter being an owner of multiple gay bars, including one that got raided — to issue a joint statement calling for legislators to “end the discrimination against queer venues and strip clubs.”

“These venues, vital for safety, celebration and self expression, face potential shutdowns due to invasive raids and restrictions on alcohol service by enforcement,” they wrote. “The intersectionality between the queer and sex work communities is underscored by the statistic that 50% of sex workers identify as queer, highlighting the urgent need to address discriminatory laws such as the Lewd Conduct WAC that disproportionately affect this overlapping demographic.”

The movement of the bill through the House was a “massive relief,” for Zack-Wu, who has spent the past few weeks of the legislative session frantically lobbying to secure votes for its passage.

There will always be people who need to strip to survive, said Zack-Wu, who started dancing at 18 to make money. She wants that experience to be “as safe and healthy as possible.”

“I experienced a lot of bullshit being an 18, 19-year-old in a strip club, and really needing the job,” Zack-Wu said. “Things were bad — really bad at certain points — but I always had the sense that they didn't need to be that bad.”

Now, if the bill clears its final hurdles, her dreams for a safer stripping industry could come true.

The business of stripping

Despite what happened to her in that dim, curtained room of Deja Vu, Ashe Ryder still loves to dance. It’s not something she does because she has to — it’s a career she chose for herself.

Ryder graduated with a degree in biology from Washington State University, hoping to go into veterinary medicine, but lost her passion for the field. To pay off her tuition costs, she drove to Spokane to audition at Deja Vu. She showed up with her simplest underwear and only pair of heels; but, because of her talent — she had taken pole classes since high school, and founded a pole club while in Pullman — was rapidly promoted out of “amateur night.”

It’s more than just the demanding physical labor of dancing, Ryder said. “It’s talking to people, making them feel wanted and indulging in whatever fantasy they have.”

Sometimes, that’s letting clients give her a foot rub. Sometimes it’s listening to them talk about their day.

Ryder found a home there, quickly learning the ins and outs of the business. She leaned into the comedic element of performance, dressing up in costumes not usually associated with strippers. She would dress up as the Grinch in lingerie for Christmas shows. In one act, she’d dress as a grandma with a walker. In another she’d appear as Guy Fieri, from the Food Network show Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives. She even had her birthday party at the club, a wild event that Ryder says ended up being one of the club’s busiest nights ever.

She resents when people use language that defines her as an exploited woman. “I have fun with my job. I make it silly, I make it serious, I make it fun. I make it my own thing,” Ryder said. “I don't need saving. I've saved myself.”

When Deja Vu closed in September 2023, Ryder threw one last party to say goodbye.

“The club was my home. I spent a lot of time there, and I loved it,” she said. “My hometown had just been lost to a wildfire [the Lahaina fires in August 2023], and it was almost like I was losing my home again.”

Suddenly, Ryder and about 30 other dancers found themselves without a job. Now, she does what’s called “travel dancing” full-time, driving or flying to other states to perform in clubs. It sometimes pulls her away from her home in Spokane for weeks at a time.

“I don't need saving. I've saved myself.”

When RANGE interviewed Ryder, she was calling from Las Vegas, where she’d been dancing at clubs for the week of the Super Bowl. It wasn’t as profitable as she’d hoped, so afterward, she traveled to Wisconsin to squeeze in a bit more dancing.

“It takes us away from our families, it takes us away from our personal life,” Ryder said. “It’s hard on your body to travel so frequently.”

Even before Deja Vu closed, travel dancing was more profitable than staying in state, and she’d spend some weekends driving up to Portland to perform at clubs there. The stage rents were lower, and because the clubs could serve alcohol, the profit margins were better for both the clubs and the dancers.

Labor of love

Ryder isn’t the only Spokane-based advocate who has been pushing for legislation to protect strippers. SAW has other dancer-members in the region, and representatives from local advocacy groups like Spectrum Center and Pro-Choice Washington have made lobbying trips to Olympia to show their support for the bill. RANGE interviewed these organizations on their support for the bill after they returned from lobbying.

KJ January, the director of advocacy and policy at Spectrum Center, said there were community fears that if state codes aren’t changed, local queer-centric venues like Nyne and The Globe — which sometimes have go-go dancers, drag queens and other performers who wear outfits that could be considered “lewd,” by LCB officials — could see the same kind of raids that hit Seattle bars.

She also pointed to the huge overlap between queer people and adult entertainers, and the increased rates of violence against both groups (Queer people are four times more likely to be a victim of violent crime than non-queer people), as a reason why it was a policy priority for Spectrum Center, which focuses on intersectional activism and advocacy.

Both January and Sarah Dixit, the organizing director at Pro-Choice Washington, highlighted the importance of guaranteeing bodily autonomy. If someone wants to be “scantily clad” near alcohol, they should be allowed to do that, January said.

“‘Our bodies, our choice’ is a value that we hold dearly within the trans community and the genderqueer community,” January said. “Repealing the lewd conduct WAC is a step towards saving lives.”

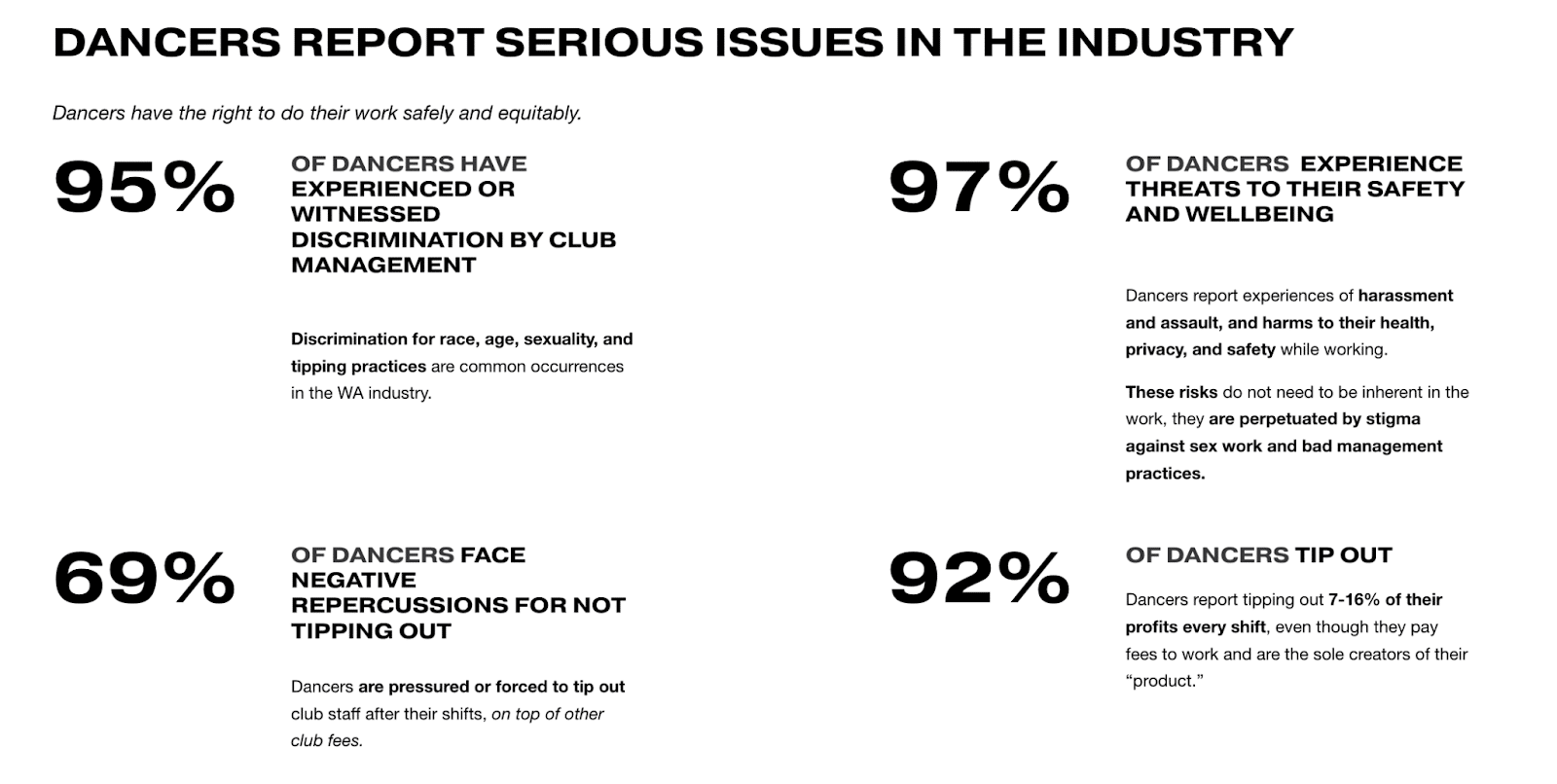

Dixit also spoke to RANGE about the intersectional nature of the issue, citing statistics from a survey SAW put out that surveyed 108 dancers in Washington and Oregon found 70% of dancers in Washington identify as BIPOC and 70% identify as 2SLGBTQIA+.

“It is not our job to police what people do with their bodies,” Dixit said. “For folks who are dancing or stripping or involved with sex work in any way, it’s their body. They should be able to work and be paid a fair wage and not be stigmatized for their labor.”

That’s been a tenet of advocacy from dancers, who have been fighting for the right to make their own decisions about their bodies, specifically when it comes to allowing alcohol near nudity. In the SAW survey, 90% of dancers agreed: alcohol should be legalized in clubs statewide.

“We all know that prohibition doesn’t work. We all know that controlling peoples’ bodies and telling them what to do doesn’t work,” Zack-Wu said. “There really is no one better than the individual to figure out what they need to be doing.”

Amy-Marie Merrell, the co-executive director of The Cupcake Girls, an organization that works to provide resources and support to members of the adult entertainment industry and those affected by sex trafficking, said that she’s heard plenty of horror stories from dancers about clients ignoring their right to consent.

“People are like, ‘She had her clothes off, why can’t I jam my finger up her ass?’ You cannot treat somebody the way you want to treat them because you’ve watched a bunch of porn and you think you have the rights to them,” Merrell said. “They are laborers. They’re providing a service. They have autonomy.”

She hopes that with the bill requiring other employees of the club, like security guards, to undergo sexual harassment training, they’ll be better informed and prepared to help defend the bodily autonomy of dancers. Advocates for the bill also believe that it will decrease sex trafficking.

A screenshot of results from SAW’s survey of dancers in Washington.

“It’s an anti-trafficking bill at its core,” Ryder said, adding that, by codifying protections for strippers and by allowing alcohol in clubs in a monitored, regulated way, dancers will be more financially stable and at lesser risk for engaging in unsafe situations.

After last year’s abrupt closure of Deja Vu, whose thin profit margin took a terminal hit after COVID-19 shutdowns, around 30 dancers were left unemployed. A Christian organization called Helping Captives bought the club and held a stage-smashing revival event in early February. Though the organization claims they’re helping victims of human-trafficking, members of SAW fear that by taking away one of only around 10 clubs in the state, Spokane strippers have been put at a higher risk for trafficking.

“Financial instability is the number one marker of vulnerability to trafficking,” Zack-Wu said. “When these clubs are dead, and also when you’re disempowered and you’re criminalized and you don’t have basic rights, that is what causes exploitation and trafficking.”

Merrell, who is not a sex worker but has worked to provide services to a few of the dancers left out of work and traumatized by the closure, purchase and subsequent stage-smashing at Deja Vu, told RANGE that while unemployment “may not immediately lead to trafficking, it immediately leads to all sorts of other vulnerable situations.”

Because of the stigma surrounding sex work, Merrell noticed strippers and adult entertainers often find it difficult to break into other fields, and when things get tough, it can become easy to fall prey to trafficking — like a pimp at a club promising dancers a quick buck if they just sleep with a couple of people.

She said that those who care about protecting people from human trafficking should be directly supporting the people most at risk — dancers and other members of the adult entertainment industry — with direct donations and mutual aid.

Merrell, Zack-Wu and Ryder all made the same point: anyone who wants to protect people from sex trafficking should be in support of a bill that guarantees worker protections and more financial stability for dancers.

“The reforms outlined in the Strippers’ Bill of Rights are not radical. These reforms are fundamental protections for an industry plagued by exploitation,” wrote Merrell, in an op-ed for The Seattle Times. “It is time we see stripping for what it is — work — and ensure protections for these workers.”

Dixit shared that sentiment, hoping that folks from Spokane would continue supporting the bill in its last push across the finish line.

“Spokane is a labor town,” she said. “Hopefully people can be ready to back up folks from all types of labor.”

‘The halls of power’

When the bill cleared the House on Tuesday evening, Ryder jumped on a Zoom call with other dancers from SAW to watch the floor debate together. The House had a few other bills to discuss, but when they came to the Strippers’ Bill of Rights, Ryder’s group call went silent.

Ryder was anxious the bill wouldn’t pass. A Republican representative SAW had been trying to gain allyship with and thought they’d won over voted no. Zack-Wu, who was watching the vote from the House Floor in Olympia, thought they’d whipped up just barely enough votes for it to pass.

But, as the votes rolled in, everyone in the Zoom call was in shock — the bill passed the House 58-36. Though they were in different cities, Ryder and Zack-Wu were doing the exact same thing: crying tears of joy and relief.

“Everyone left the Floor and a couple people started hugging me, and I just started bawling ugly fucking tears,” Zack-Wu said. “One of my very close friends, another dancer-leader, and I talked that night on the phone and she was just like, ‘I can't believe that you were standing there in the halls of power when this change happened and then they actually embraced you as a sex worker.’ The fact that we live in that reality is amazing.”

The work isn’t done for Zack-Wu, though, who is already thinking about the next steps for SAW’s advocacy work. She wants to make sure everything in the bill is implemented, and clubs actually start receiving licenses from the LCB. She wants to tackle the strict zoning laws that make it nearly impossible for new clubs to open, especially in areas with higher density. She wants to fight for better working conditions for people like bikini baristas.

Eventually, she dreams of full decriminalization of sex work in Washington.

For Ryder, who comes from a family of entrepreneurs and who had once hoped to buy Deja Vu, the support for the bill has revived one of her long standing dreams: to not just dance in the state she calls home, but to own her own club here. On her way from her most recent travel dancing trip, she recalled telling the friend she’d traveled with, “Wouldn't it be so great if I could just open a club in Spokane and we wouldn't have to do this traveling thing anymore?”

When the bill passed the House, that was her first thought: “Oh, my gosh. I can actually open something now.”

“I want other women to have the same financial opportunity that I had in a safe environment by someone who understands what it's like being in the industry,” said Ryder. “That's my end goal.”

Aaron Hedge contributed reporting.

Editor’s Note: Erin Sellers was formerly employed by Spectrum Center and is the former colleague of the advocacy and policy director interviewed here.