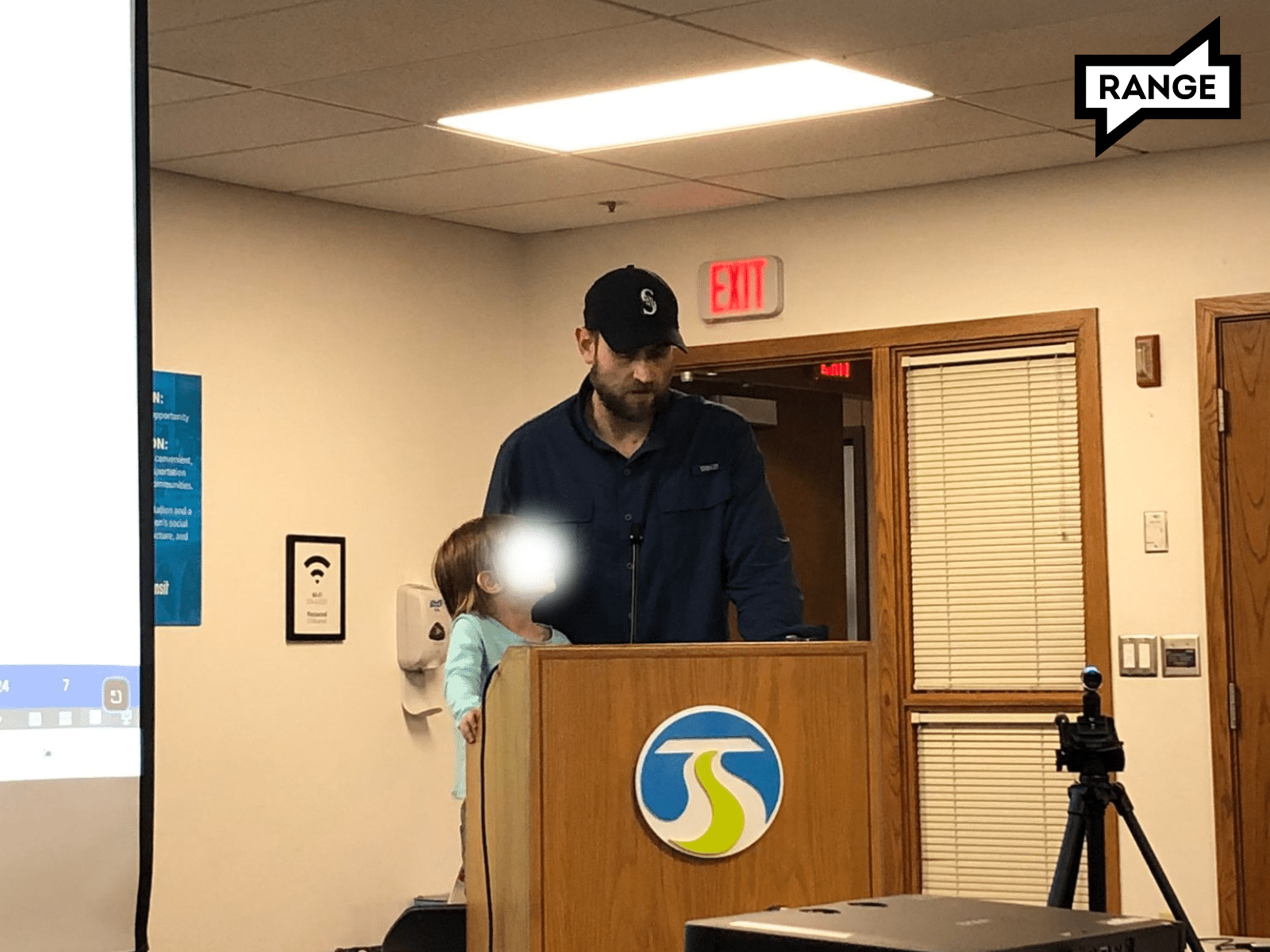

On March 21, transit advocate Erik Lowe pulled a chair up to the podium nestled at the back of the Spokane Transit Authority (STA) board room. Lowe lifted his four-year-old son Teddy up onto the chair so he could lean into the mic and tell the board members how much he liked riding buses #4 and #74 — the lines he and his son had taken to get to that afternoon’s board meeting.

Lowe then gave his own testimony, a brief show of support for a proposal to make bus fare free on all lines during Expo ‘74 brought by the Spokane City Council’s representation on the board. His son thanked the board for their time and hopped down from the chair.

For about an hour, Lowe watched more of the meeting while Teddy watched the buses pull in and out of the bus barn — a favorite activity of his, according to Lowe. “The only thing he loves more than a bus is a train,” Lowe said.

Then, the younger Lowe got restless and the pair decided to leave.

“I went to take him into the bathroom because we have an hour bus ride home,” said Lowe, who lives in Spokane Valley. One of the multiple transit security officers at the board meeting got up and followed them, standing outside the bathroom waiting for Lowe and his son to come out.

When they were done, Lowe said he asked the guard point blank, “Do you follow everyone into the bathroom? Or just me?”

According to Lowe, the guard stammered, “I don't know, this is my first time working the board meeting, so I don't know.” The guard followed Lowe and his son all the way out to the main door. The interaction left Lowe bristling, so he notified RANGE and put in a public records request with the agency to see if staff had specifically flagged him for surveillance.

A month later, the records request confirmed that Nancy Williams, STA’s Chief Human Resources Officer, had ordered additional security for meetings Lowe was scheduled to testify, and to pay special attention to his presence.

‘Looking for answers’

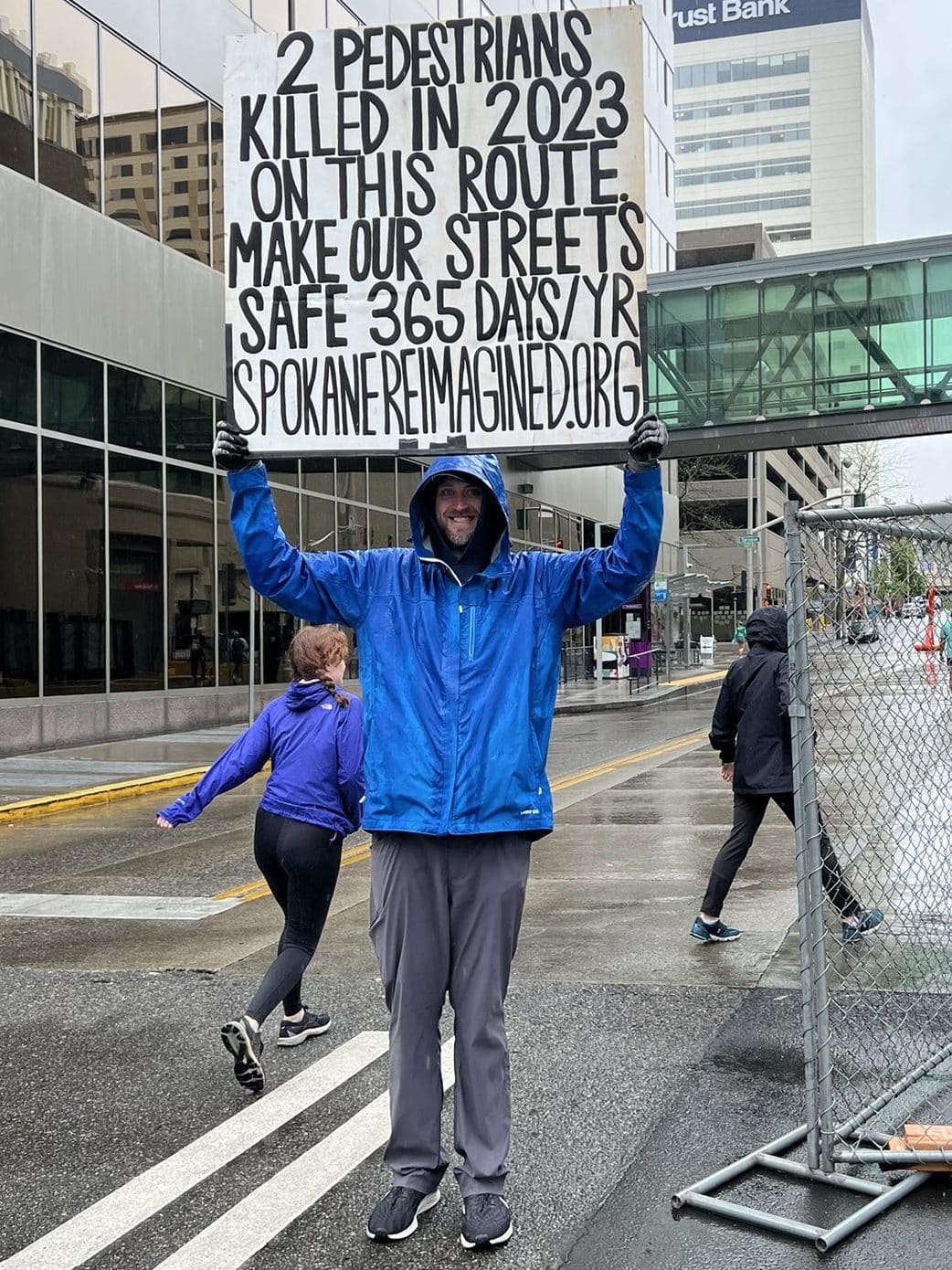

Lowe is a transit advocate who has gotten press recently for an ambitious plan to make Spokane’s roadways safer for pedestrians and bicyclists. He gets amped up talking about it.

He only started testifying at STA board meetings in January — after RANGE broke the news that board members and the STA CEO Susan Meyer had been making coordinated efforts to stall transit priorities championed by Spokane City Council Members Zack Zappone and Betsy Wilkerson.

“Previously, I haven’t been too involved in STA politics largely because of the competence and professionalism of STA staff. From the drivers to maintenance to planners to customer service, they’re all top notch and I salute each of them for their hard work and commitment to their community,” Lowe told the board during his first public testimony.

His words for the group were pointed, and especially so toward Meyer and Board Chair Al French. “I’d like you to explain why you lead a transit agency: Mr. French as chair of the board, Ms. Meyer as CEO of Spokane Transit, with seemingly no desire to actually serve the mission of the agency,” Lowe said. “Spokane Transit Authority deserves so, so much better than you two.”

But Lowe wanted to do more than just give comment, so he applied for both a paid position at STA and a volunteer position on the Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC). Lowe wasn’t chosen for either position, which he didn’t initially think was strange.

But then he heard from Dan Brown, a friend who chairs the CAC, that Lowe’s application for the volunteer position hadn’t even been sent to the committee as an option.

In a February 7 email, Brown told Lowe that STA Chief Communications Officer Carly Cortright had recently sent the CAC just three applications. Lowe’s application — which he sent to STA in December — hadn’t been one of the applications sent to the CAC for consideration.

Frustrated and looking for answers as to why his application had been held up, Lowe wrote a statement and delivered it during public testimony section of the next STA meeting, on February 15.

“I have my thoughts on the CAC’s byzantine appointment process, but I’ll leave that for another time. For now, I’m looking for some answers,” Lowe said at the conclusion of his planned testimony. “So, Dr. Cortright, could you please explain to the board why my application wasn’t brought forward for consideration?”

Lowe had finished what he’d come prepared to say (he posts his full written statements on Twitter in advance of public meetings, and hands them out to reporters as well) but French quickly chimed in, saying “We’re not going to engage in conversations.” A quick back-and-forth between Lowe and French ensued, with Lowe describing his qualifications for membership on the CAC and his passion for engaging with STA.

“You were talking about the CAC earlier and how it’s important for citizens to engage with the board,” Lowe said. “How are citizens supposed to engage with the board when you have staff screening their applications in order to prevent them from joining the CAC?”

French responded, “We can take it up with our staff.” The exchange ended with both men giving curt “thank yous.”

Lowe attended the rest of the meeting, then left without issue. He said he didn’t try to talk to any staff or board members outside of the public testimony portion, and none of them approached him to chat, either.

The next day, he sent an email to all board members, Meyer and Cortright following up on his comments and asking for clarification on what happened with his application. He received no response. A week later, on February 23, he sent a second email asking why there hadn’t been any follow up. Lowe’s tone is chippy, and references Cortright by name.

“Commissioner French, in his capacity as STA Board Chair, said staff would reach out to me. No one has. If my job title was Chief Communications and Customer Service Officer, I'd try to be at least decent at communications or customer service, but I guess ‘head in the sand’ is considered a legitimate comms strategy by some,” Lowe wrote. “Now I'm forced to speculate as to why my application hadn't been seen by the CAC. Did Dr. Cortright’s assistant take it upon herself to screen applicants?”

On February 28, Meyer emailed him back, stating that the CAC would review applications in a March meeting that would be open to the public. In early March, CAC chair Brown emailed Lowe to say, “[Meyer] and I have discussed our concerns that applications were not getting to the committee and I think that this practice of "pre-screening" will not continue.”

In early March, Lowe’s application was discussed by the CAC and he was chosen for an interview, but ultimately not chosen as an applicant that would be forwarded to the STA board’s Performance Monitoring & External Relations (PMER) Committee for approval (although, recently the CAC had a resignation, so Lowe may get another chance.)

On March 8, Lowe also called the hiring manager for the paid Associate Transit Planner position he’d applied for, and said he was told by her that she’d never received it for review — it hadn’t been forwarded by the HR department.

All of that confusion and frustration had built up for Lowe. He sent RANGE a timeline of his experiences on March 9, complete with hyperlinks and email forwards of his communications with STA staff and board members. Ten days later, he submitted a records request to STA for all staff and board communications with his name in it, and a day later, he attended the March 21 board meeting with his son Teddy, where they were followed closely by the transit officer.

‘Visibly upset and angry and shaking.’

On April 25, Lowe sent RANGE a collection of documents he’d received from his public records request, including an email exchange between Williams, STA’s Chief Human Resources Officer and transit officer Warren Earp.

“Thanks for sticking around tonight. Sounds like it was uneventful, which is good!” Williams wrote to transit officer Warren Earp on March 12, when Lowe attended a public meeting of the CAC.

“Of course. Always a pleasure. Lowe was accepted for an interview; if that gets scheduled on a Tuesday I will be happy to stand guard,” Earp responded.

Williams concluded the exchange by writing, “Wonderful! Thank you so much!”

In her capacity as Communications Officer, Cortright told RANGE that while having transit officers present for public board meetings is standard practice to prevent disruptions, officers had been specifically asked to attend meetings when Lowe would be in attendance, because of his comments at the February 15 meeting.

“He was pretty hostile toward me and accused me of burying his application to the CAC,” Cortright said. “He was visibly upset and angry and shaking.”

Cortright said that while she understood what she saw as Lowe’s anger, “considering what he thought had happened,” his demeanor caused a few staff members to be concerned. Cortright did not say who these few staff were, other than herself. “For everyone’s benefit, I will just say that people were made uncomfortable and in the abundance of caution a request was made.”

So, the next time they saw his name on the sign-up sheet for public testimony, they arranged for officers to be in attendance.

RANGE reviewed the video footage of the meeting, and though Lowe’s voice remained level for most of his testimony — with the exception of the back and forth with French — because of the camera placement of the recording, his demeanor isn’t visible.

We called French, Spokane Valley Mayor and STA board member Pam Haley and Spokane City Council Members Kitty Klitzke and Paul Dillon who also sit on the STA board to ask about Lowe’s presence at meetings. French and Haley did not answer requests for comment. Dillon, who was also a reference on Lowe’s CAC application, said he’d never seen Lowe visibly angry or “shaking.”

“Eric can get personal at times,” Dillon said. “But to me, it’s nothing I think merits this response.”

Klitzke said that she’d never felt threatened by any of his testimony either at STA or at Spokane City Council meetings.

“I’m not a particularly sensitive person. I am a veteran, I’m also a medic. I don’t think I ever would’ve described him like that. Agitated would be the word I’d use,” Klitzke said. “But I think I probably would’ve noticed if he was shaking, because I would’ve been concerned … for his physical or mental health, and I am trained to observe those kinds of things.”

Lowe said he was more nervous than anything else — he’s terrified of public speaking. “I’m never angry or agitated,” he told RANGE. “I was accusatory because I was questioning why my application was shelved, but that is my right because it’s a public forum.”

Both Klitzke and Dillon acknowledged that Lowe is a tall guy, with Dillon comparing their heights and saying he knows that can cause people to perceive him as a threat, (Lowe is 6’9” and Dillon is 6’5”). Klitzke said it seemed Lowe was aware of the perception of his height, and may have brought his son as a way of showing he was not a threat.

Lowe himself acknowledged his height in a text to RANGE, stating “I know I’m a big guy, but I don’t think I’m particularly dangerous. According to their org chart, STA has 16 transit officers. I’ve seen three standing around outside a single board meeting,” he wrote. “Am I expected to start throwing furniture or something?”

Cortright said STA has a total of 23 security positions on staff including the manager and leads, as well as 16 contracted security positions. She also said there hadn’t been any “further issues,” with Lowe after the February meeting. Heightened security at meetings he attended afterwards were just “an abundance of caution,” she said.

The heightened security was also to address increased public presence at meetings in the new year, Cortright added.

‘It’s like Fort Knox in there’

While Lowe seems to be at odds with STA leadership like French, Meyer and Williams, one thing they can all agree on is the importance of transit safety. They disagree on how to get there, though.

Board members like Haley and French have been regularly bringing up safety concerns as a reason to steer away from free fare policies, with Haley saying free fare in the past had turned buses into “rolling jails,” and French claiming that in other cities, it had transformed buses into “mobile homeless shelters.”

Lowe said he also wants to see STA prioritize driver safety, as they’re the organization’s “best resource,” but doesn’t think that French and Haley have the best perspective on that. “You're going to sit there and you're going to talk about transit safety and complain about the safety of our drivers,” Lowe said, “But you don’t ensure [drivers] are safe by having your transit officers loitering outside of board meetings and chilling outside the Plaza’s customer service office.

Cortright couldn’t give details on STA security protocol, to “protect the integrity of our security plan,” but said that officers do random patrols and try to hit every route multiple times a month. Drivers can also request security if they’re noticing “a particular pattern of behavior,” on their route.

Lowe said he’d ridden the bus more than 20 times since he moved to Spokane, and he’d never seen an officer on the bus, though he’d seen plenty “standing inside the customer service office” at the Plaza. Dillon rides the bus weekly, often three or four times a week, and said he had also never seen a security officer on his bus line — “only at the STA plaza.”

Lowe found it frustrating that STA was “wasting resources babysitting,” and said security at STA board meetings went way overboard compared to the other meetings he attends, like Spokane City Council, the Spokane Regional Transportation Council and the Board of County Commissioners: “It’s like Fort Knox in there.”

Dillon and Klitzke, who sit on the dais for one of, if not the single spiciest meeting in the region — the Spokane City Council — both found the security presence a little overblown. Dillon described it as “weird,” Klitzke went into more detail.

“I tend to think we have too many security guards at meetings. Sometimes we have five police officers at city council meetings and that I feel like is a bit much,” she said. “In a lot of situations I’m surrounded by too much security and the STA security, I feel like they’re a little more like police officers than our City Hall guards so having four of them there at some of our meetings seems a bit much.”

Dillon said it was extremely disappointing that Williams had asked transit officers to spend time watching Lowe.

“Erik is not a threat, he’s a very engaged advocate. It’s just ridiculous and demonstrates a pattern of hyper-defensiveness,” Dillon said. “Protest and accountability are an important part of the job, and if you don’t want it to be, then you’re in the wrong role for the wrong reasons.”

Editor's note: A sentence was added to provide more context to the increased security presence at meetings.