In 2021, persistent heat killed 19 Spokane County residents. In 2023, the Gray Fire killed a person and destroyed hundreds of buildings in Medical Lake. This year, a stretch of the Spokane River dried up completely near Barker Road for the first time in recorded history. The county has been in a state of drought for the last four years.

Such events are more common now than in the past due in part to warming temperatures caused by manmade greenhouse gas emissions, which trap heat.

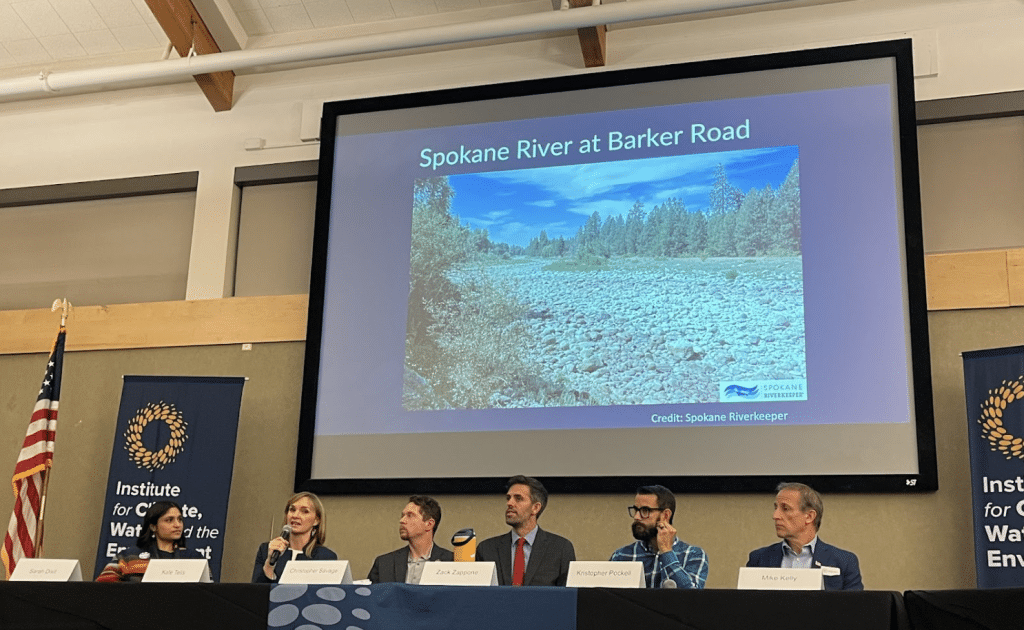

With this in mind, candidates for Spokane and Spokane Valley city councils gathered last week at Gonzaga University to deliver their positions on current and proposed climate policies in Inland Northwest governments.

The event was hosted by the university’s Institute on Climate, Water, and the Environment (ICWE) titled the Candidates Climate Change Forum, which has been running for the last seven years. The discussion focused largely on long-term community plans, which the city of Spokane and Spokane County are in the middle of crafting. (You can watch the event here.)

Long-term plans dictate how certain kinds of land can be developed, where public transit can be built and how wide, straight and fast streets can be, among other things. All these characteristics influence how many miles motorists drive and the carbon footprints of buildings, which are the primary producers of climate warming gases.

Six of 13 invited city council candidates showed up: for the Spokane City Council, Sarah Dixit, who’s challenging incumbent Jonathan Bingle for his District 1 seat; incumbent Zack Zappone and challenger Christopher Savage for District 3; and Kate Telis for District 2. For the Spokane Valley City Council, Mike Kelly and Kristopher Pockell competed.

This was the first forum that included candidates from Spokane Valley, according to Brian Henning, the founder and director of the ICWE and moderator of the forum.

The candidates’ proposed solutions — some of which are mandated by state law and others pioneered by city governments — focused on dense city building, expanded public transit and zoning that allows different kinds of buildings to be constructed in the same neighborhoods.

One consistent theme of the night: local governments can act against climate change, but only when their budgets align with the solutions they come up with.

Kelly, a conservative gunning for the Spokane Valley City Council seat that will be vacated by Rod Higgins next year, sits on the city’s planning commission and delivered something of an urbanist vision for future development. His comments focused on the layout of the city, though he did not directly mention climate change.

“I’d love to see some sort of European-style mix where you have residential over retail … that people can actually own,” Kelly said. “This would provide not only some low income, entry-level housing, but it would be a good use of our space where we can build up a little bit on the five lanes of Appleway and Sprague.”

New state requirements for local governments encourage suggestions like Kelly’s, Henning said in an interview. But local government policies that encourage people to drive less and local building regulations that curb emissions are central to the fight against climate change.

“The series of questions on comprehensive planning, you’ll see it as central to not only adapting to living with climate change, but solving the problem,” Henning said. “The county, for the first time ever, is going to have a plan that has a chapter on reducing emissions.”

Pockell agreed with his opponent.

“There are still a lot of areas where it’s just vacant land waiting to be developed,” Pockell said. “Rather than contributing to that urban sprawl, [it’s important to find] those places and develop those and get higher density, more than just single family homes.”

Candidates said they wanted to solve environmental problems, but some noted the budgetary concerns of financially strapped cities might hamper those efforts. Some parts of local communities are impacted more than others.

Zappone and Dixit both advocated for progressive taxation of wealthy people and large corporations at the state level, which would ostensibly free up funding for things like safe places for people to go when temperatures are too hot to safely stay outside.

“Sales tax is a big burden on folks who are living paycheck-to-paycheck who have the lowest incomes in our city. That’s not equitable,” Dixit said. “We need to make sure people are paying their fair share. If we’re all experiencing climate change, that needs to be an expectation.”

But Washington, like Spokane, is also in a budget crunch. Kelly, who said he prefers private-sector solutions to government action, and other candidates noted these solutions all depend on government revenues and budgeting, a fickle practice that often doesn’t consider long-term considerations like climate change.

“We all understand that we can have anything that we want as long as we’re willing to pay for it,” Kelly said.

Savage echoed Kelly’s comments.

“The city’s in a $13 million deficit,” he said of Spokane. “It is going to be very, very difficult to try to open these shelters and implement weather areas because we just don’t have the money.”

He advocated, instead, for cheaper programs, like the urban tree-planting effort SpoCanopy, to expand areas of the city that are cooler because they are under shade. Savage said he has personally planted 100 trees in Spokane over the last decade.

But, when pressed by moderator Brian Henning, Savage said he would cut the tree program if it came into conflict with funding police or fire response services.

Zappone, who is campaigning for reelection on a platform of making Spokane more dense, noticed that climate-friendly planning is good for the budget in the long-term because a smaller city geography necessitates less services to far-flung areas.

“If we are planning for growth outside the city, we have to then start planning for water towers outside our city, pump stations outside our city,” Zappone said. “Those things are costly and have more water use, more congestion, more irrigation.”

At other forums, Zappone and Savage have found themselves at odds when it comes to development, with Zappone advocating for density and Savage the annexation of more county land for single-family home sprawl.

The conversation also addressed other ways local governments can respond to climate change. A certain amount of warming is unavoidable because national governments across the globe were too slow to curb it. As a result, the climate in most environments is hotter, which in the Inland Northwest translates to a water shortage. Scarce water is an unfortunate problem for a place like Spokane County that consumes it at nearly 300 gallons per capita every day, around three times the national average.

This consumption is one of the culprits of a dry Spokane River.

Spokane has required its residents to curb this consumption by banning lawn watering during the hottest parts of the day and encouraging landscaping with less grass and more local flora. But there is no enforcement mechanism for these policies, the candidates said.

Kelly said the region could conserve water by building relationships with large water consumers like ranchers, farmers, golf courses and other entities that have fields of plants to keep hydrated.

“Agriculture is big in this area and of course, they’re using a lot of water,” Kelly said.

But, the candidates agreed, the city of Spokane seems not to follow its own rules when it sometimes waters its parks in the hottest parts of the day.

“We need to start with commercial businesses as well as the highest users and the city needs to lead by example,” Telis said. “People are confused about what the water regulations are because the city is not actually following through on that.”

Zappone added that the reason the city waters during the day is because park staff only water during working hours, and the city does not have money to install automated systems. He said voters should approve a parks levy on ballots this fall that would allow the city to install automated watering systems.

During the forum, Henning instructed the audience to show approval or dissent by waving, respectively, a provided green or red sheet of paper rather than clapping or heckling. Green flags tended to flash when candidates supported government action on climate change and red ones when they said government was too limited or the wrong actor to address the crisis.