The Spokane City Council unanimously passed a resolution in early November that formally endorses the creation of 27 new miles of low-stress walking and cycling routes by 2027. Spencer Gardner, Spokane’s Planning Director, presented the mobility plan to the Public Infrastructure, Environment, and Sustainability Committee in October. The plan is not yet fully designed and no funding source has been decided on, so city council was not voting to spend exact dollars, but rather to show formal support for Mayor Lisa Brown’s administration to continue planning the network.

The “27 by 2027 Urban Mobility Network” would fortify a few of Spokane’s many existing neighborhood streets to make them comfortable for users of all ages and abilities to walk, ride a bike or use a mobility device. There are a handful of strategies the city is considering using to accomplish this:

- narrowing the streets with curb extensions to make them uncomfortable to speed on in a vehicle

- adding medians which force drivers to turn off the calmed segments so they cannot be used as through-streets

- adding crosswalks at arterials that include flashing lights to stop traffic

A good example of the changes needed to make a mobility network is in Vancouver, Canada, which has many quiet neighborhood streets designated as bikeways, where each arterial has an enhanced crossing with a button accessible from the seat of a bike.

Vancouver’s 14th Avenue, shown here, is a designated bikeway — you might notice the 30 kph speed limit sign (that’s 19 mph!) and the bike icon on the overhead street sign. When folks riding on 14th Avenue need to cross this arterial — Oak Street — they can easily stop car traffic by pressing a button accessible from the seat of a bike that triggers a red light.

Why this matters

If you’re unfamiliar with this concept of a “mobility network”, think of it like Spokane’s network of arterial streets: Division Street, Francis Avenue, Maple/Ash Streets, Hamilton Street, Grand Boulevard, 29th Avenue, etc. If you were driving from Kendall Yards to Holy Family Hospital, you probably wouldn’t drive up the neighborhood roads of Cedar Street to Everett Avenue – you would probably stick to roads like Broadway Avenue, Maple Street, or Wellesley Avenue.

Now imagine an arterial network like that, but for your kid walking to school, your neighbor cycling to work or your parent rolling to the store on a mobility device. But unlike arterial networks for cars, this mobility network requires very little room. After all, it only takes the width of a cycle track to move as many people on bikes as seven-lane-wide Division Street can move in private cars.*

The city has specifically highlighted parks and schools along these routes, so it seems one goal of the resolution is to increase rates of walking and riding to school. (I hear the school drop-off lines are horrendous, so I think we’d all like to see fewer cars in those lines.)

Unfortunately, Spokane has a lot of bike lanes, greenways and paths that don’t connect to any other bike infrastructure. The cycle track on Illinois Avenue in the Logan neighborhood or the Fish Lake Trail southwest of Spokane are great while you’re on them, but getting to and from them can be hairy, so their usefulness in terms of transportation is limited.

Gardner, the city’s planning director, stresses the importance of the network, these low-stress segments being connected to one another.. It’s a simple idea, but a true network opens up a lot of combinations of routes and guarantees one can get anywhere on the network once the nearest segment is reached.

Slowing or lessening car traffic on neighborhood streets also has benefits for our community that aren’t directly for people looking to cycle through them:

- Less maintenance may be required on these streets: my cargo ebike causes about 1/50,000th the wear and tear that my Subaru Crosstrek does.

- Front yards may be more comfortable to play or relax in.

- Those on foot will be safer, as vehicle versus pedestrian collisions will both decrease and be less dangerous when they do occur because of the slower speeds.

- Research in London even found streets like these decrease crime due to the presence of people.

- Quieter soundscapes (who doesn’t appreciate that?)

- Decreased pollution.

*Here’s the math: at Wellesley Avenue, Division Street has seven lanes and a speed limit of 35mph. At that speed, each lane has a maximum throughput of roughly 700 vehicles per hour, or 4,900 vehicles per hour across all lanes. If each car averages 1.6 people, we reach a max throughput of 7,840 people per hour. An urban two-way cycle track maxes out at 7,800 people per hour.

Where it might be

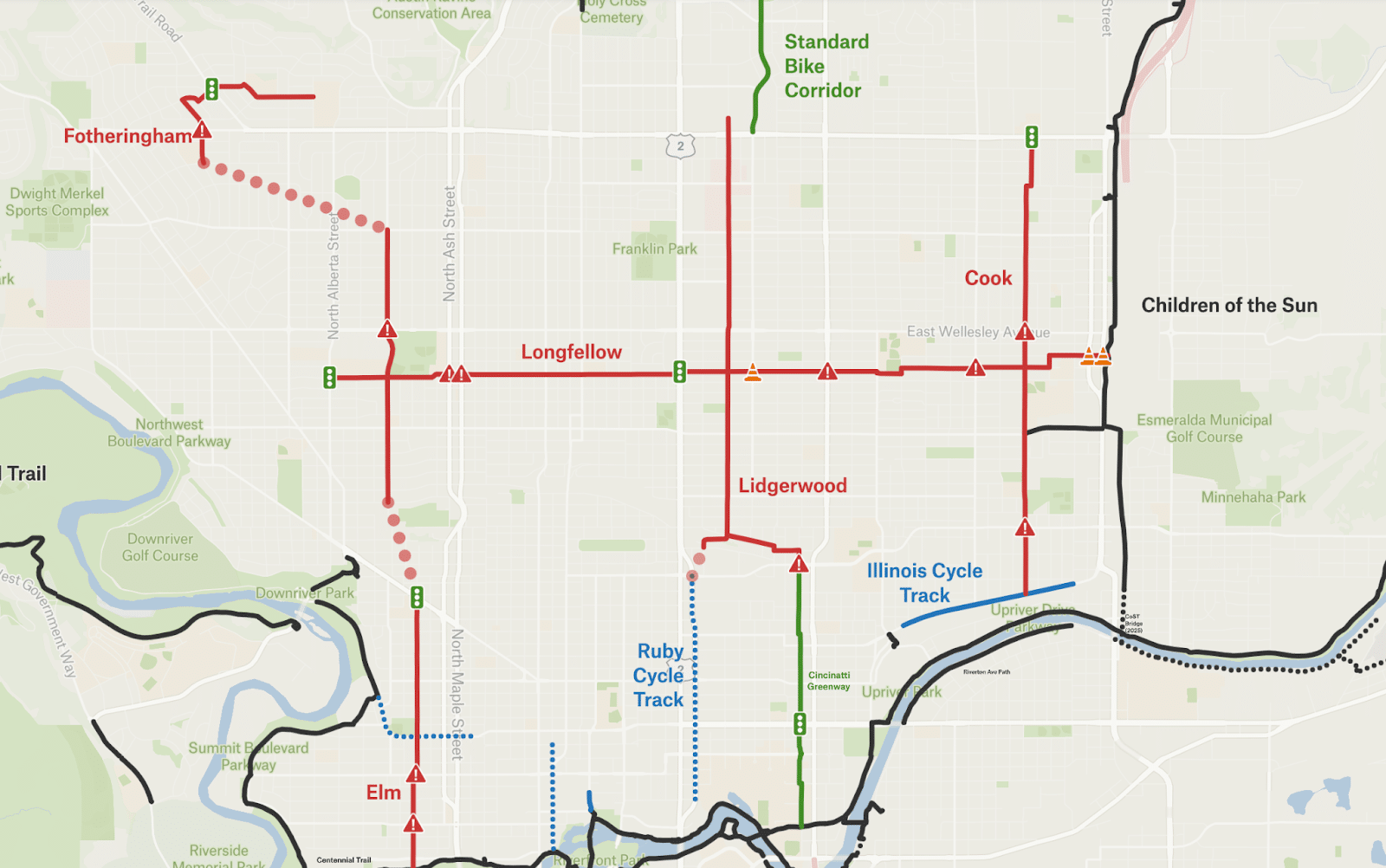

We don’t have all the location details yet. The city’s planners made an abstracted map without concrete specifics to (I can only assume) prevent people doing exactly what I’m doing, which is overanalyzing each stretch. Apologies to my planner friends.

Their overarching plan is for the network to link to existing trails like the Centennial Trail, Children of the Sun Trail, Ben Burr Trail, Fish Lake Trail, an existing greenway on Cincinnati Street and the upcoming Ruby Cycle Track.

To get an idea of how this network may look in about 2 years, I made my own *unofficial* map. Here’s where I imagine the network will run, based on the abstract map the city provided and my own knowledge of our streets, but fair warning: I could be misinterpreting the city’s graphic, and things could definitely change between now and construction time. In fact, Gardner mentioned to me that his team may realign segments based on other planned projects (like enhanced crossings).

(Find my analysis and explanation of the routes after the following section.)

A cool $6 million

Costs are not yet finalized, as the project has not yet been designed, but Gardner estimates it will cost around $6 million. That seems like a lot of money, but for 27 miles, it is an absolute bargain compared to car infrastructure.

For reference, the city of Airway Heights will spend $1.8 million on repaving just one mile of Hayford Road. The city of Spokane will spend $4.7 million on a single roundabout. And WSDOT will spend another whopping $412 million on the remaining 3.5 miles of the north-south freeway.

Gardner mentioned that a big chunk of the bikeway cost is the roughly six lighted crossings — the project could require more, but back-of-the-napkin math tells me six crossing lights would cost around $2.5 million (based on what the city has paid recently for lighted crossings on Division). So I’m hoping that leaves around $3 million for diverters, bump outs, refuge islands, wayfinding, 20 mph speed limit signs and planters, many of which can be built on the cheap.

In the spirit of being fiscally responsible, the plan uses infrastructure that already exists (streets, lighted crossings added in previous traffic calming cycles, bumpouts added in previous Safe Routes to School projects) and stretches those dollars quite far.

Funding could come from a variety of sources, including state grants, federal grants, the city’s contract with Lime or the traffic calming fund (which is fed by traffic camera tickets).

Gardner also assured city council at the October 21 public infrastructure meeting that this would not disrupt any planned traffic calming projects – only 2025’s Traffic Calming Cycle 12 is currently planned.

I also asked Gardner directly about the other bike infrastructure projects planned and he assured me none of these would be delayed by 27 by 2027 – in fact, the network relies on some of these other projects.

An unofficial analysis of my unofficial bike network map

NORTH

Elm Street through West Central

This segment takes advantage of a fantastic little path next to Audubon Elementary School and one of the few pedestrian crossings on Northwest Boulevard.

Tough crossings: Broadway Avenue and Boone Avenue. I imagine some refuge islands could do the trick.

Belt Street or Cannon Street through Shadle

The topography in this area (the “north hill”) causes our street grid to break down, which makes finding a candidate for the mobility network somewhat challenging. Belt is perhaps the most direct option, but it’s certainly not the most calm. There’s a nice crossing at Cannon and Wellesley though.

Tough crossings regardless of which north-south street is used: Garland Avenue and Wellesley Avenue.

Fotheringham Street

It’s not clear how the planners hope to connect the Belt Street/Cannon Street segment to Fotheringham, but it allows the network to reach Westview Elementary. This street is the most direct northbound route through Balboa, and could potentially take advantage of a new lighted crosswalk at Holyoke Avenue.

Tough crossings: Francis Avenue.

Longfellow Avenue

Two enhanced crossings have been installed on Longfellow in recent years: at both Alberta Street and Division Street. It’s good to see the network taking advantage of previous investments.

This one does meet Children of the Sun Trail in Hillyard (I do love to see network connections!).

Tough crossings: Maple Street, Ash Street, Monroe Street, Nevada Street and Crestline Street.

Lidgerwood Street

This segment uses a very convenient and lightly trafficked route up the north hill that Strava users know as the “Lidgerwood Chute”. It is narrow and restricted to one-way (downhill) vehicle traffic, but I’d support removing vehicles from it altogether due to its blind corners and steep 7% grade.

This segment would connect to the future Ruby Cycle Track as well as the existing Cincinnati Street Greenway.

Tough crossings: Wellesley Avenue and Francis Avenue.

Cook Street

The city of Spokane had already been planning to construct a greenway on Cook Street in 2028. Gardner tells me it's possible that the city could use quick-build, temporary solutions on Cook Street, then come back with something more substantial in 2028.

The Greenway would meet the cycle track on Illinois Avenue, a segment sorely lacking in network connections.

Tough crossings: Wellesley Avenue and Euclid Avenue.

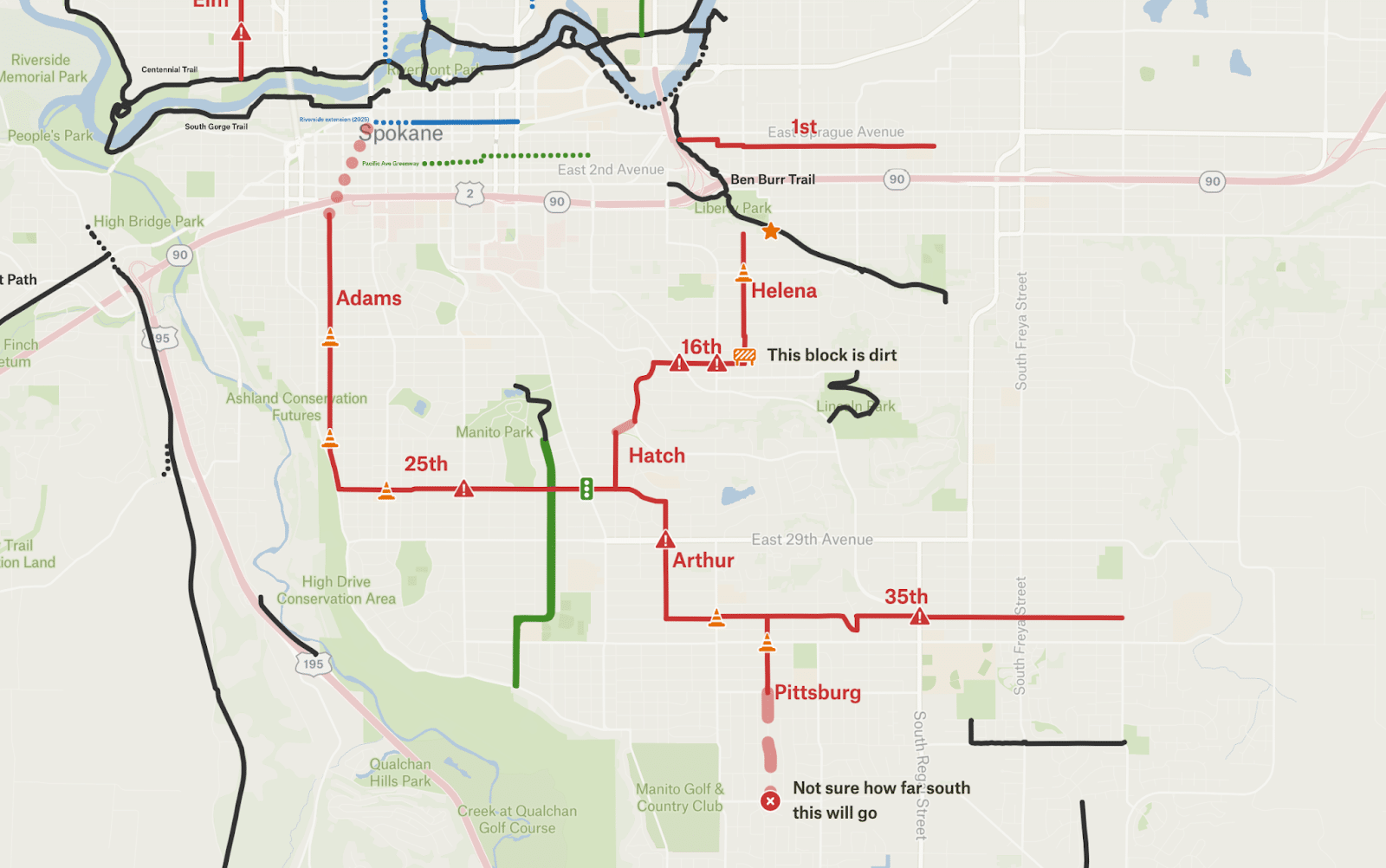

SOUTH HILL

Adams Street (with a bit on Cedar Street)

Aside from the obvious grade going up the South Hill, the toughest part of this segment will be getting out of downtown and under I-90 — there are only so many underpasses.

I’m admittedly less familiar with the South Hill, but this seems like a solid route. I typically ride Walnut Street/Cedar Street/High Drive but I may just have to switch to Adams Street. Fun fact: the route features some of Spokane’s remaining brick streets.

Tough (but not that tough) crossings: 14th and 21st Avenues

25th Avenue

Overall, this one makes sense. There is already an enhanced crossing at Lincoln Street, it just needs a button accessible from the seat of a bike. And there is a stoplight at Grand Boulevard – hopefully the stoplight can detect a cyclist.

Tough crossing: Bernard Street.

Hatch Street

The South Hill is not lacking in small, calm neighborhood streets, and this segment is no exception.

16th Avenue

Tough crossings: Southeast Boulevard and Perry Street.

Helena Street

Some of these blocks are dirt. I’m not sure how I feel about that, as it’s not the most comfortable to ride on, but does slow down cars. This segment should connect to the Ben Burr Trail at some point – perhaps at the end of Hartson Avenue.

1st Avenue

This segment seems like a nice parallel route to Sprague Avenue and connects with the Ben Burr Trail. It has sharrows painted on it (which unfortunately can do more harm than good), so I suppose it was already intended to be a bikeway.

Tough crossing: Napa Street.

Arthur Street

This segment is popular among my bike friends on the South Hill. The city has applied for a grant from WSDOT to build an enhanced crossing at 29th Avenue, which will be helpful here.

35th Avenue

This segment would allow access to any destinations on 37th Avenue, including Ferris High School and Hamblen Park, and gets close to Chase Middle School.

Tough crossings: Perry and Regal Streets.

Pittsburgh Street

I’m not sure how far south the planners intend to run this.

Tough crossing: 37th Avenue.

These 27 miles, in addition to everything else planned for construction by 2027, will make a fantastic start to a true low-stress network.