If the headlines from earlier this week are to be believed, more than half of unhoused people in Spokane aren’t actually from our city.

Much of the local media ate it up.

“Report: Over 50% of Spokane homeless population moved there after losing housing,” the headline from The Center Square proclaimed.

“Study reveals over half of unhoused moved to Spokane after losing housing,” reads a headline on Fox 28 and KHQ.

KREM had the most nuanced headline: “Leaders clash over study claiming more than 50% of those experiencing homelessness moved to Spokane from elsewhere.”

One big problem? None of these stories actually analyzed the study, its backers or the narrative it's trying to weave about Spokane, instead choosing to report a sensational statistic that is likely inaccurate — according to a prominent expert on homelessness data.

The survey cited in these stories was commissioned by the Spokane Business Association (SBA) and designed by President Donald Trump’s former homelessness czar Robert Marbut. One of the most obvious issues with the study is a sample size so small it’s hard to make accurate conclusions about the findings. Further, the survey questions themselves seemed designed to create a specific result — that most homeless people in Spokane aren’t from Spokane — by using questions about birthplace and school attendance to break people into two tracks: individuals with “direct connections to Spokane,” and “visitors,” who should be given a bus ticket back to wherever their family is.

Under Marbut’s rubric, which we’ll discuss in greater detail below, a majority of the RANGE team — to almost the same percentages found in the SBA survey of unhoused people — would be put into the “visitors” category.

Preparation for the survey included conducting a “grid search” to estimate the total number of unhoused people on Spokane streets, used to calculate how many people surveyors needed to contact to get representative data. That data was collected by volunteers who drove around the city flagging people who looked homeless. There was no consistent control mechanism for duplicates or filtering out people who may have looked homeless but had shelter or housing.

Large chunks of content in the Spokane study were copied word-for-word from another Marbut did in King County on behalf of the Discovery Institute, a Seattle think tank first known for pushing schools to “teach the controversy” meaning teach biblical young Earth creationism alongside accepted science.

“ There's no methodology. It doesn't tell us how many people they interviewed. It doesn't provide any base statistics regarding the people other than median age,” said Dr. Dennis Culhane, a homelessness and housing researcher at the University of Pennsylvania (who served as Director of Research at the National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans from 2009 to 2018. “So it's hard to really call it a study.”

So if news stories parroting a study that contradicts past findings and which doesn’t have raw data to allow specialists to corroborate its conclusions, with policy recommendations copied and pasted from a Seattle survey isn’t cutting it for you, join us for a deep dive to correct the record on homelessness data in Spokane, and analyze what the SBA narrative says about our city.

The Story

The survey and the rapid-take news coverage that followed may not tell an accurate story, but they do tell a story about Spokane that is both familiar and seductive: there are people who are not “from here.” Those people are a drain on our resources and if we could just send them back to where they came from, our community would be better off.

The implicit moral of the story: If these unhoused aren’t “our” people, then their homelessness is not our problem.

It’s a story that long predates the SBA survey. Three years ago, Mayor Nadine Woodward said “we make it easy to be homeless.” Rumors of people from less hospitable jurisdictions being given bus tickets to Spokane have been around for decades, repeated last year by Phil Altmeyer, CEO of Union Gospel Mission, one of the shelters where SBA conducted many of its surveys for this study.

The story is not unique to Spokane.

Marbut told an almost identical one with his survey in Seattle. Similar stories about the unhoused are told across the country.

This is a refrain heard everywhere,” says Culhane. “ Every community in this country thinks that they're doing the greatest thing on homelessness and that they are a magnet for homelessness. I scarcely find anyone who doesn't claim that ‘We're so good to the homeless, everyone wants to come here.’”

The only problem with that story, Culhane says, is that it’s largely untrue.

“When researchers have actually gone to measure these things, they don't find a very strong relationship between migration and homelessness,” he said. “ People are not usually shopping for a good place to be homeless, and I hardly think that Washington State is a place you would go to because the weather is good.”

Even Barry Barfield, administrator of the local homelessness coalition, who was among the volunteers who helped conduct the survey for SBA, says that while he agrees with “99% of the policy recommendations in the Marbut report,” he just doesn’t buy the narrative that 50% of unhoused people in Spokane aren’t from here.

And Barfield thinks Marbut knows it, calling him a “highly educated individual” who knows how to create reliable surveys. Given that pedigree, Barfield believes, “[Marbut] knows that what he’s asking is not getting a reliable response.”

“I think it is his business model,” Barfield said. “I don't think he is being dishonest, unless you think used car salespeople are being dishonest when they hype the beautiful paint job but ignore what is under the hood,”

“This is just my assumption: That he is hired partly to produce an answer like that. Spokane Business Association hired him and they, I'm sure, are thrilled with that 50% answer,” Barfield added.

Still, Barfield is on board with most of the survey's recommendations for what to do about homelessness in the city, which include treatment and long-term recovery for unhoused people struggling with addiction — just not the recommendation to only provide those services to a select group of people who have deep ties to the area.

Even if the two-track model of resources for some and a ticket to elsewhere for people “not from here” was implemented, Barfield thinks that very few people would leave because “ a significant portion of homeless people have connections with Spokane and putting them on a bus and sending them home will be of no service to them whatsoever.”

“ My bottom line is I strongly support 99% of his report. I just don't think you can draw a conclusion that half the folks have no connection with Spokane.”

Of course, there are kernels of truth: some people are given a bus ticket to Spokane from other cities, though usually it is through programs that require proof of a family connection to Spokane.

The cry of “people are bussed here!” is only half the story: Spokane busses people elsewhere, too.

“We cannot pretend like Spokane is doing something completely different than everybody else because we have two programs in town that bus people wherever they wanna go,” said Julie Garcia of Jewels Helping Hands, the operator for some of the city’s scattered site shelters. “We've bussed hundreds and hundreds of people to other cities.”

There’s an additional wrinkle to this story: the people who aren’t bussed anywhere. The Airway Heights Corrections Center is a major part of the state’s carceral system. People from across the state are imprisoned just minutes from downtown, and are often released with no resources: no bus ticket home, no job lined up, no safety net.

In Garcia’s experience doing outreach to the prison, this accounts for some of the percentage of people who are from Washington, but not Spokane.

“People are brought here from other parts of our state, and then when they're released, they're just let out the door with no resources, no way to get back to where they had resources and they fall into the homeless trap,” Garcia said.

Many other communities face this same burden; Airway Heights is one of 11 state prisons.

It’s the same story told about immigration — see a log of Trump’s comments on immigrants.

“Immigration and homelessness, same thing, same problem,” said Garcia. “It's othering an entire community. It's making them less worthy to receive services or help than people who were born here. And none of us were ‘born here.’ This is not our country — this is stolen land.”

The statistics

One of the largest surveys of unhoused people ever conducted in the United States — a study by Association of Military Surgeons of the United States members studying Veterans Affairs records of more than 100,000 homeless veterans from 2015 — found that just 15.3% of veterans who were homeless “migrated across large geographic areas while they were homeless.” The rest stayed close to the area they originally sought homelessness services in.

In broad strokes, data collected by the city over the years matches these findings.

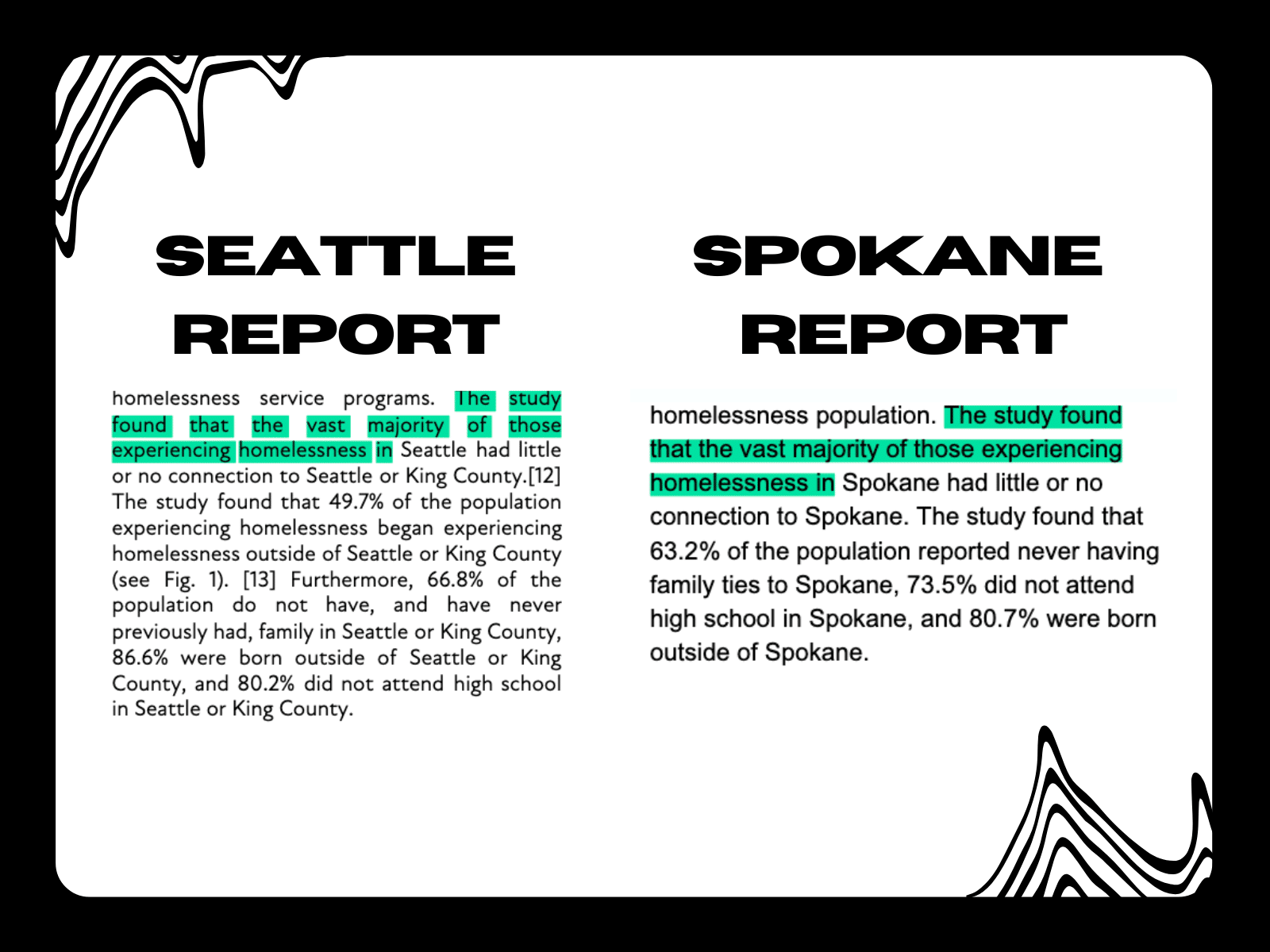

SBA’s Marbut study, by contrast, reports that 50.2% of the people they talked to in Spokane had been homeless before they came here. More than 80% of unhoused people, the study asserted, were not born in Spokane. More than 60% have no “family ties” to Spokane, and 73.5% did not attend high school here.

Those are some shocking statistics, especially because they’re dramatically different from two separate studies conducted with city-collected and national data on homelessness and its causes.

In Spokane, data from the 2024 Point-In-Time (PIT) Count found that roughly 80% of unhoused people in Spokane are from Spokane County, while 85% are from Washington and the remaining 15% are from the Pacific Northwest, which aligns much closer with national data.

There’s three big differences between SBA’s data and the city’s data that could explain the huge difference in results: sample size, type of study and the questions each being asked.

Sample size 101

While SBA’s published study results didn’t include a sample size, they told reporter Belle Lewis of KHQ (who wrote a story doing some actual data breakdown of the survey) that the sample size was “about 230 surveys.” (However, reporting from KREM states the survey included 260 people.)

Today, Marbut told RANGE they analyzed 223 complete surveys and excluded 30 to 35 surveys that were turned in incomplete because they would throw off the calculations.

“Without all the data [filled in], we could not use [incomplete surveys] since it would kill the calculations,” he wrote in a text to RANGE.

For a poll to be truly representative of a population of people, it needs to be conducted in such a way that a representative survey of the population is taken — or a statistician would need to control for discrepancies. Neither the PIT count nor Marbut’s survey claims to have done that level of analysis, so neither survey can purport to be a “representative” sample of the unhoused population.

In general, though, collecting data on more people will diminish the impact of what statisticians would call “extreme” or “very unlikely” observations. When sample sizes are too small, you run a greater risk of accidentally polling a clump of people who don’t truly represent the whole group.

For example, if you did a poll about the favorite color of goth bands, but only polled one band who happened to prefer pink, you might wrongly conclude that pink is the chosen color of goth culture. If you interviewed five bands, you might still poll the band that likes pink, but you’d also likely get four others who say they prefer black.

Where Marbut and SBA say they polled 223 people, the city’s PIT Count had a sample size of 2,021 unique people — more than 9 times more.

Still, Marbut claimed in a text to RANGE that his survey has a “99% confidence level with a 6% error margin.” In the same text, he quoted different numbers explaining how confidence and margin of error work, “Our 95% confidence level had a 4% error margin [This means we had a 95% chance that all the data was within 4% of the error rate].”

He came to this conclusion by putting the total number of unhoused people in downtown at 403 — the 403 individuals identified by a grid search with no unique markers (though Marbut said they took photos to compare) or control for whether or not a person was actually unhoused — and claiming 223 fully completed surveys is “a 55.3% penetration rate — which is VERY HIGH completion. As a comparison, political polling runs about 3.5%.”

A high penetration rate only matters if the 403 people he counted was a coherent population — either all of Spokane’s unhoused or all of our “visibly” unhoused or unsheltered and unhoused — but there’s no indication that it is.

If the PIT count of 2,021 of unhoused is closer to the correct count of unhoused people, then Marbut’s penetration rate drops to just over 11%. If the real number is even higher — as it almost certainly is, because people who are living with friends, or sleeping in their cars in areas not covered in these counts — the penetration drops further.

Despite these issues, Marbut told RANGE he has “very high confidence, if not 100% almost 100%,” that his results are more accurate than the city’s data.

Type of study

According to Culhane, there’s an even deeper issue with the SBA study — and Spokane’s PIT count, for that matter.

Both the SBA study and the PIT count are cross-sectional studies, which means they pull a sample from a given point in time. SBA conducted studies over the course of almost two weeks, Marbut said. The city’s PIT count data was collected over the course of seven days.

Culhane says cross-sectional studies have “ tremendous bias in the sample,” because they combine people who have been homeless for a long period of time with people who are newly homeless, which makes it hard to interpret meaningful characteristics about a population.

Culhane said that data collected from a cross-sectional study do not account for the large chunks of people who exit homelessness quickly. For that more rigorous approach, you need a longitudinal analysis, which would examine Spokane’s homeless population over an extended period of time.

“ When you look at these point in time surveys, they tend to look like most of the people are chronically homeless,” Culhane said. “They've been homeless for very long periods of time. They have very complex service needs and you're inclined to think that that's what causes homelessness, when in fact, it's different.”

Luckily, Spokane already has this more robust longitudinal analysis data — collected from its Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) database, comprised of ongoing data collection from “a diverse range of service providers and organizations located throughout Spokane County.”

In 2024, the city’s Longitudinal Systems Analysis (LSA) found that 7,221 unique individuals had sought homelessness services that year — a much larger sample size.

Data both from the LSA and from by the confidential HMIS system aligned with the PIT count’s findings, city spokesperson Erin Hut said, showing that around 80% of the people who received homelessness services in Spokane were from the city or surrounding areas, like Spokane Valley, who contracts with Spokane city for shelter bed space and other services.

Survey questions

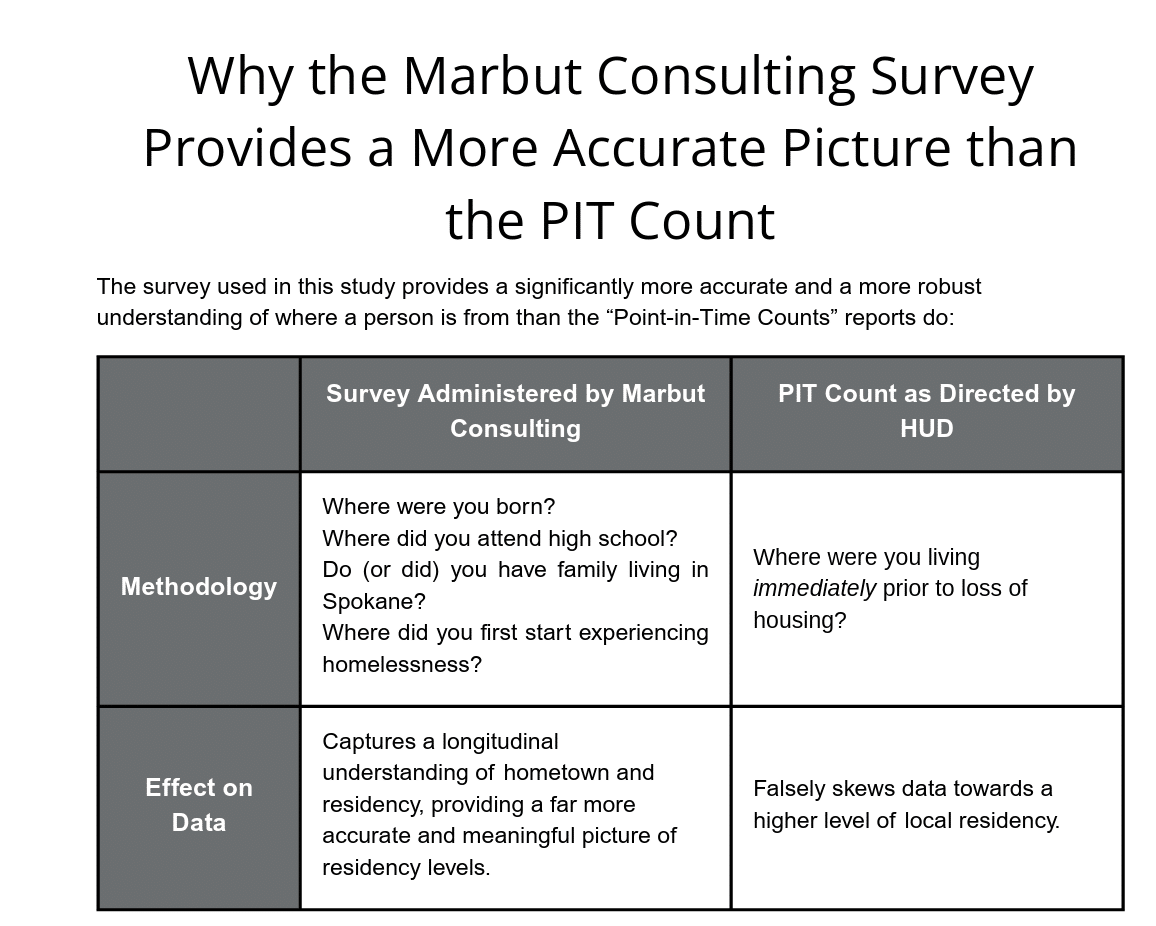

Another key difference in the two studies was the design of the survey questions.

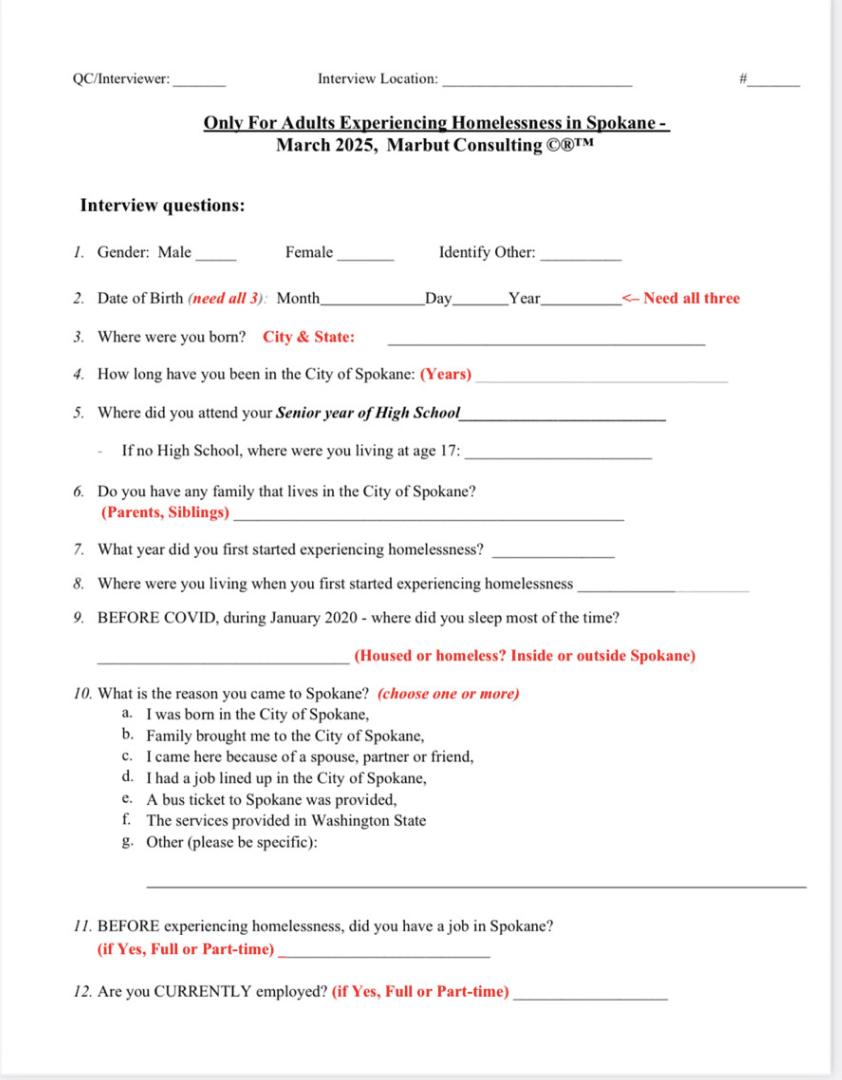

Here are the Marbut-designed questions SBA used:

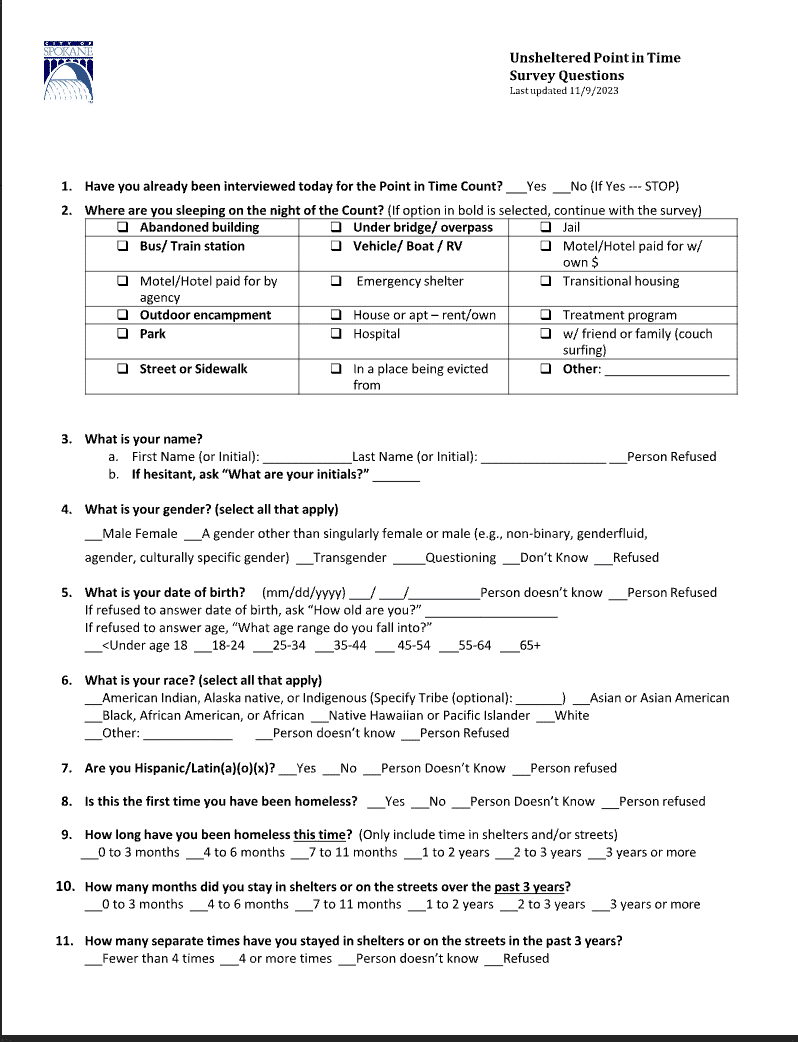

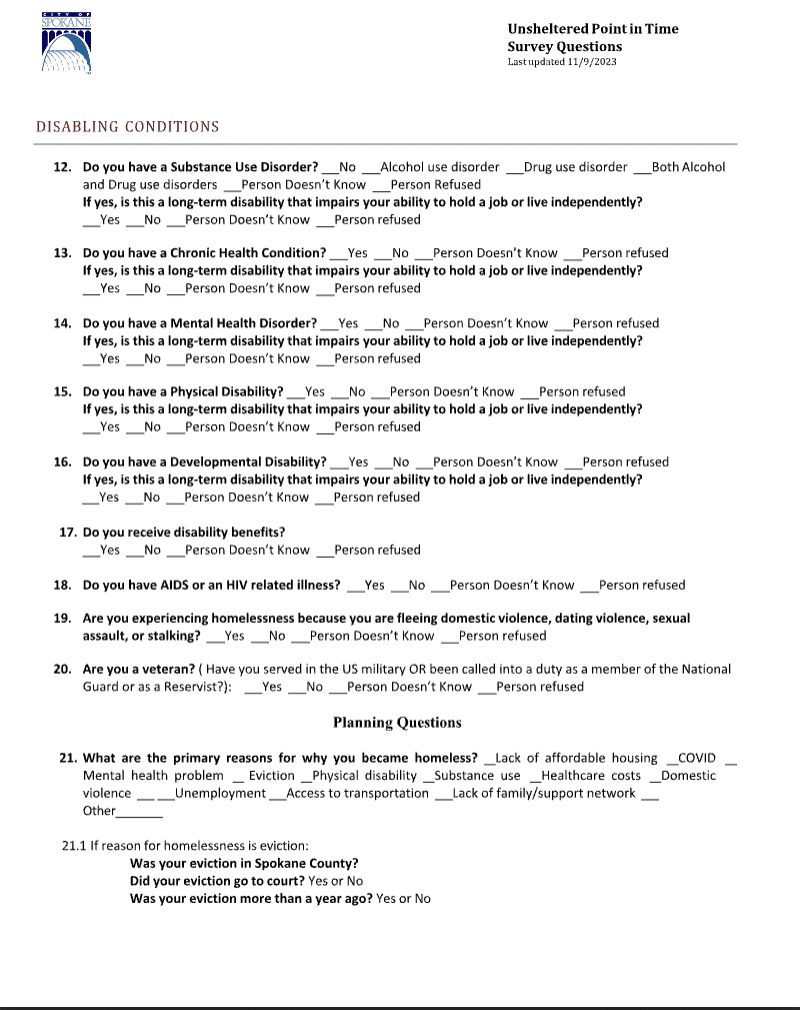

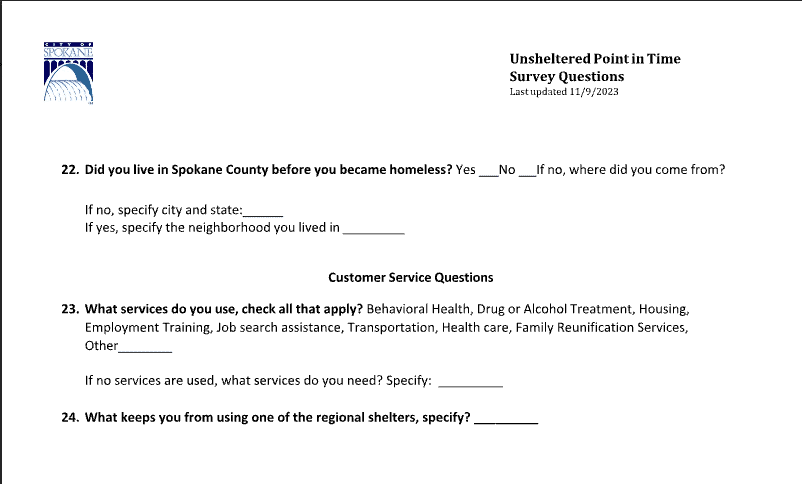

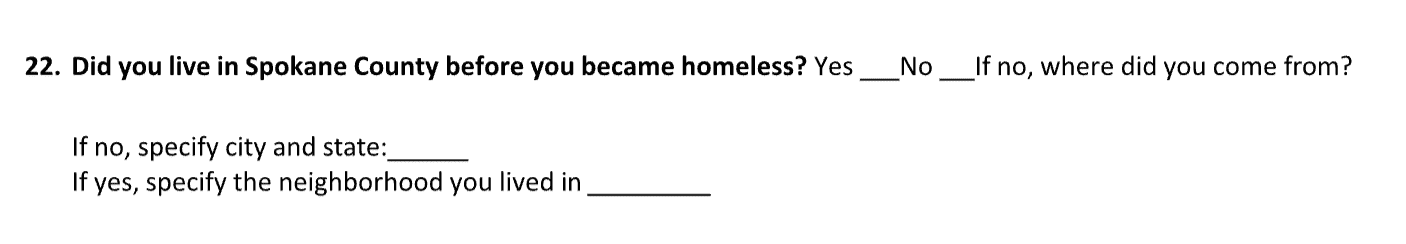

And here are the questions asked by the city on their 2024 PIT count:

There are several differences between the surveys. One key difference for this analysis: the way each survey attempts to answer the question of “are you from here?”

The Marbut-designed study asks for high school attendance, where someone lived when they first experienced homelessness, when they first experienced homelessness and why they came to Spokane, as well as whether or not someone has a parent or sibling living in the city.

The PIT count question asks more simply: “Did you live in Spokane County before you became homeless?”

It’s not a perfect question, by any means, but it does more accurately collect data to answer the question: is any given surveyed homeless person “from here.”

Still, despite all this, he thinks his methodology is more accurate than the PIT count data, at least on this one issue of local residency, because city data “falsely skews data towards a higher level of local residency.”

Citation? Himself.

He’s also wrong.

Marbut highlights his questions as being better designed than the PIT survey. Culhane disagrees.

“He erroneously describes the [PIT] survey question,” Culhane said. “ The question does not say, ‘immediately before’ it says, ‘where were you before you became homeless?’”

Here’s a screenshot of the actual question:

Marbut criticizes (and misquotes) the PIT survey question, but the questions from his survey seem designed to cast as broad a net possible to catch and define the largest group possible as not being “from here,” but the questions fail to account for a number of things:

- What if a person first became homeless at a different point in their life, for example, as a child, when they lived elsewhere, but have had housing in Spokane for their entire adult life?

- What if they first became homeless in Spokane Valley, Mead, Cheney or elsewhere in Spokane County?

- What if you have no family connections here, weren’t born here, didn’t go to high school here but moved here as an adult and then decades later became homeless?

Consider the central finding of the Marbut study: 50.2% of people surveyed first experienced homelessness elsewhere, which the study authors claim “highlights that Spokane is often a secondary destination after individuals start experiencing homelessness.”

However, their own survey also found that the median age for people experiencing homelessness was 45. That’s a lot of years where someone could have first experienced homelessness elsewhere and then moved here later in their life.

Another interesting detail: one of their questions asked how long the person surveyed had lived in Spokane, which could be used to compare against other data points like length of homelessness and date of first experience of homelessness to make more accurate claims.

Though he declined to include this detail in the published findings, in a text to RANGE, Marbut wrote that of the people he surveyed, the average time lived in Spokane was 15.5 years with a median of 7 years.

He says he excluded that information because, “We wanted to focus on the critical data. The report was already getting pretty long.”

It’s worth noting that we ran the Marbut survey on the entire RANGE team; no one would have counted as fully “from here,” despite all living in the Spokane area for between three and 40-some years and making it their permanent home.

Other issues with the SBA survey

There are other big issues with the Marbut-designed study; chiefly, its lack of citations for major claims and lack of information around methodology.

“It’s hard for me to call this a study. It does not describe the sample, it only mentions that they did street interviews with some number of people,” Culhane said. “ There's no methodology: it doesn't tell us how many people they interviewed. It doesn't provide any base statistics regarding the people other than median age.”

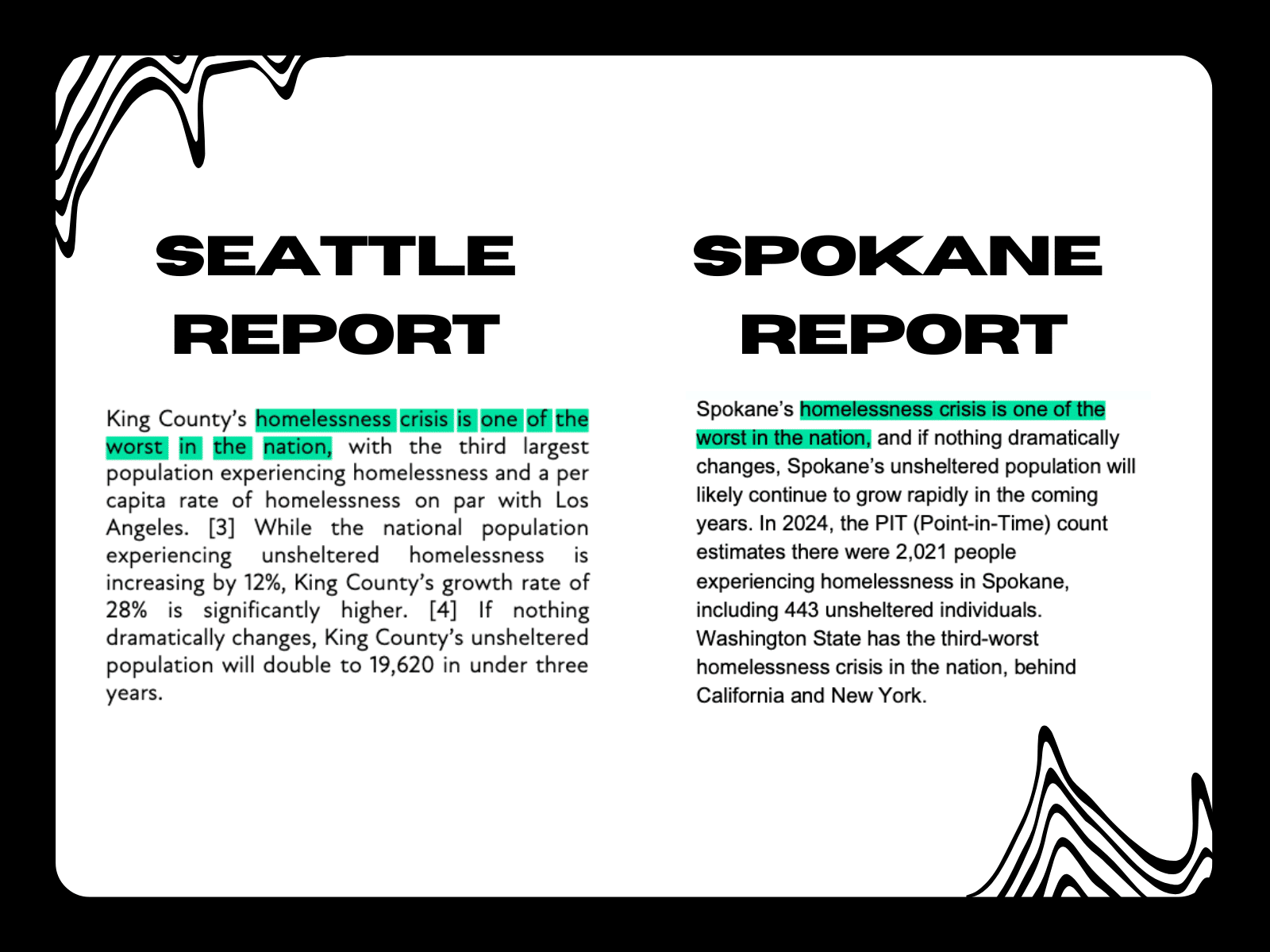

Among the big claims in the study that go uncited:

- “If significant policy and procedural changes are not made immediately, the number of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in Spokane will dramatically increase in the coming years, and will likely double in less than five years.”

- “Spokane’s homelessness crisis is one of the worst in the nation, and if nothing dramatically changes, Spokane’s unsheltered population will likely continue to grow rapidly in the coming years.”

- “‘Housing First’ policy directs funding away from wraparound services such as substance use treatment or job training programs.”

- “The prevailing policies aimed at addressing homelessness in Spokane have discontinued funding treatment for substance use disorders, removed treatment requirements, redistributed funds away from an emergency response system to long-term taxpayer subsidized housing, and utilized a one-size-fits-all approach to populations with varying needs.”

- Compared to prior Spokane observations in October 2019, September 2022 and September 2024, the number and size of dogs had increased noticeably. Of note, most of the people experiencing homelessness who had dogs with them were women. Increases in the number of dogs or the size of dogs are often a future indicator of increased levels of violence on the street.”

Marbut later told us the info about the dogs came from his previous visits to Spokane when he saw “less than three dogs,” but did not specify the actual number. He also did not say how many dogs he saw this time, or how big any of these dogs were, or where he got the information that dogs of any size are indicators for increased levels of violence.

Marbut said the lack of citations was intentional: “I've never been asked by community groups, agencies, cities, counties and states to provide citations.”

In response to Marbut’s uncited claims, city spokesperson Erin Hut stated it is illegal for the city to establish treatment requirements for any programs that receive federal HUD dollars. She also said that the city has increased funding for substance use disorders, pointing to the installments of opioid settlement dollars directed towards expanding medication assisted treatment programs and co-responding units at the Spokane Police Department and Spokane Fire Department.

She also said Mayor Brown’s administration has been specifically moving away from the “one-size-fits-all” approach used by former Mayor Nadine Woodward.

“When Trent Shelter was in place, we didn't have that kind of unique case management where we were really focused on people who have differing needs,” Hut said. “We just kind of warehoused people in a big facility and said, ‘Well, okay, they have a roof over their heads, that's shelter.’ We’ve been very firm in our approach to moving away from that because we know it's not effective.”

The Marbut survey also fails to ask about substance use or mental health disorders, instead choosing to make broad and uncited statements like “the homelessness crisis in Spokane is on track to dramatically increase in the coming years. Furthermore, 2025 projections indicate nearly 10 people within Spokane dying each week due to drug overdose, often due to fentanyl.”

One of the few citations the Marbut study did point to was a study of homelessness conducted by UC Berkeley and UCLA that found “78% of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness have a substance use disorder and/or untreated mental illness.”

Two issues with that:

- First, the number is large, but it’s another cross-sectional survey, which means researchers weren’t catching proportional amounts of people who exited homelessness quickly, or who were less visibly homeless, Culhane said.

- Second, the Marbut study is trying to draw a direct line from a study of unsheltered individuals conducted in California to the survey they ran here in Spokane. In addition to being different geographic regions with different state and municipal governments, a large chunk of people Marbut surveyed were actually sheltered individuals residing in Union Gospel Mission shelters and two of the scattered site shelters run by Jewels Helping Hands — not an exclusively unsheltered population.

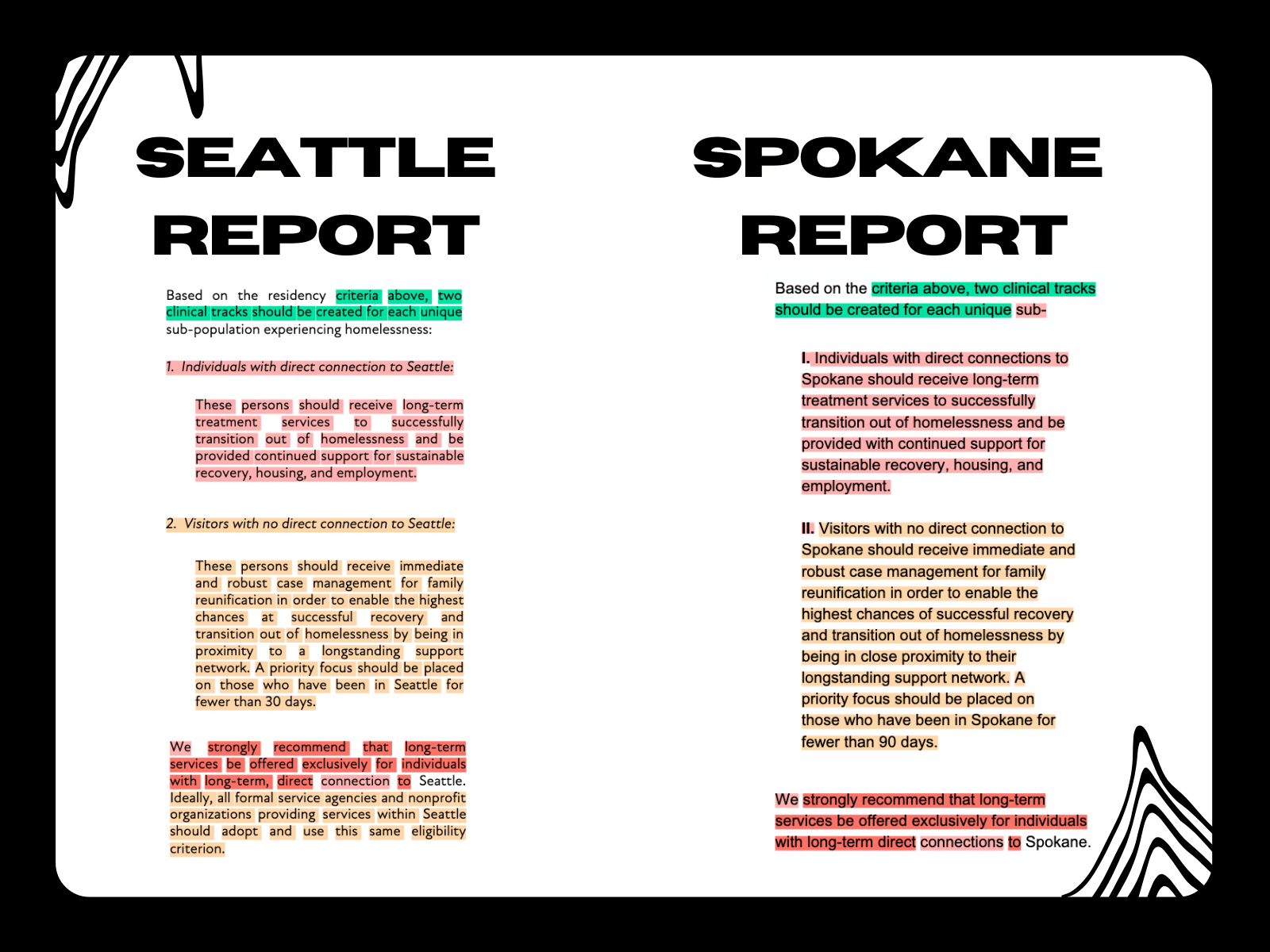

None of this data analysis touches a huge issue of authenticity: the language used in the Spokane survey report — including both the assumptions about the city and Marbut’s conclusions — is nearly identical in large sections to a similar survey Marbut recently conducted in King County.

The Source

When analyzing the accuracy of a survey, it’s important to consider the source. In the case of this survey, there are a few sources: Spokane Business Association, who paid to have it conducted, Marbut, who created the survey and prepared the report and a third source: Marbut’s earlier report on homelessness in King County that has nearly identical language to this Spokane survey.

Spokane Business Association

The Spokane Business Association is a relatively new entity in Spokane, founded in 2024 to advocate for business interests in the region.

Its relative newness, though, doesn’t mean SBA doesn’t have deep Spokane roots: founder Larry Stone is one of the largest conservative donors in the area. He’s spent millions of dollars to oppose progressive candidates, put up billboards against the Division Street Road Diet and fund the fearmongering “Curing Spokane” film.

Stone also bought the building that housed the Trent Shelter — the city’s former large congregate shelter with no running water or bathrooms for residents — and rented it to the city.

Stone hired Gavin Cooley — former CFO of Spokane, architect of the movement to create a new regional homeless authority and member of Mayor Lisa Brown’s transition team — as SBA’s first CEO.

“We’re not just another organization to stand up and say, ‘We have a crisis,’ and start throwing rocks,” Cooley said during the launch event for SBA.

Months later, Cooley started what he called 5 am Crisis Walks, where he led primarily business owners and downtown residents on early morning walks of downtown Spokane to look at homeless people and throw rocks at Brown for what he sees as her failure to properly address the city’s dual homelessness and opioid crises.

Since their inception, SBA’s efforts have mostly focused on advocating for harsher penalties for camping within city limits, pushing people to vote against statewide rent stabilization and leading those 5 am walks to demand their version of a “real emergency response.” Then, in March, they expanded their efforts to data collection, by hiring Marbut to conduct a homelessness survey.

“If we’re creating the conditions where people can come to Spokane and go to a marketplace for fentanyl and methamphetamine, like downtown, they can engage in open drug use without any intervention whatsoever,” Cooley said prior to conducting the survey, the data would reveal it.

Dr. Robert Marbut

We covered Marbut pretty deeply in an earlier piece, but here are some highlights:

- He worked under Trump guiding homelessness policy, and once argued that feeding unhoused people is enabling them.

- He is famous for his “Housing Fourth,” philosophy, which purports that people shouldn’t have housing until they have demonstrated they have gotten clean.

- During work with cities like Daytona Beach and St. Petersburg, Marbut’s recommendations have included criminalizing all behaviors associated with homelessness (like panhandling and camping on public property) and warehousing people at large congregate shelters, similar to the former Trent Shelter.

- While the Trent Shelter had no indoor showers or bathrooms, the Marbut-designed shelter in St. Petersburg went even further: though it was zero barrier, anyone who broke the shelter’s rules were forced to sleep outside in a courtyard that frequently flooded.

- Marbut also designed and executed a similar study to Spokane’s in King County, which yielded remarkably similar — and in some cases, identical — results.

The King County study: “one of the worst in the nation.”

A potential source for some of the material in the Spokane study is a similar one conducted by Marbut last year in King County, which can be viewed in its entirety here.

We ran both reports through a plagiarism checker that identified multiple sections of language that were substantively the same, and others that were cut-and-paste verbatim.

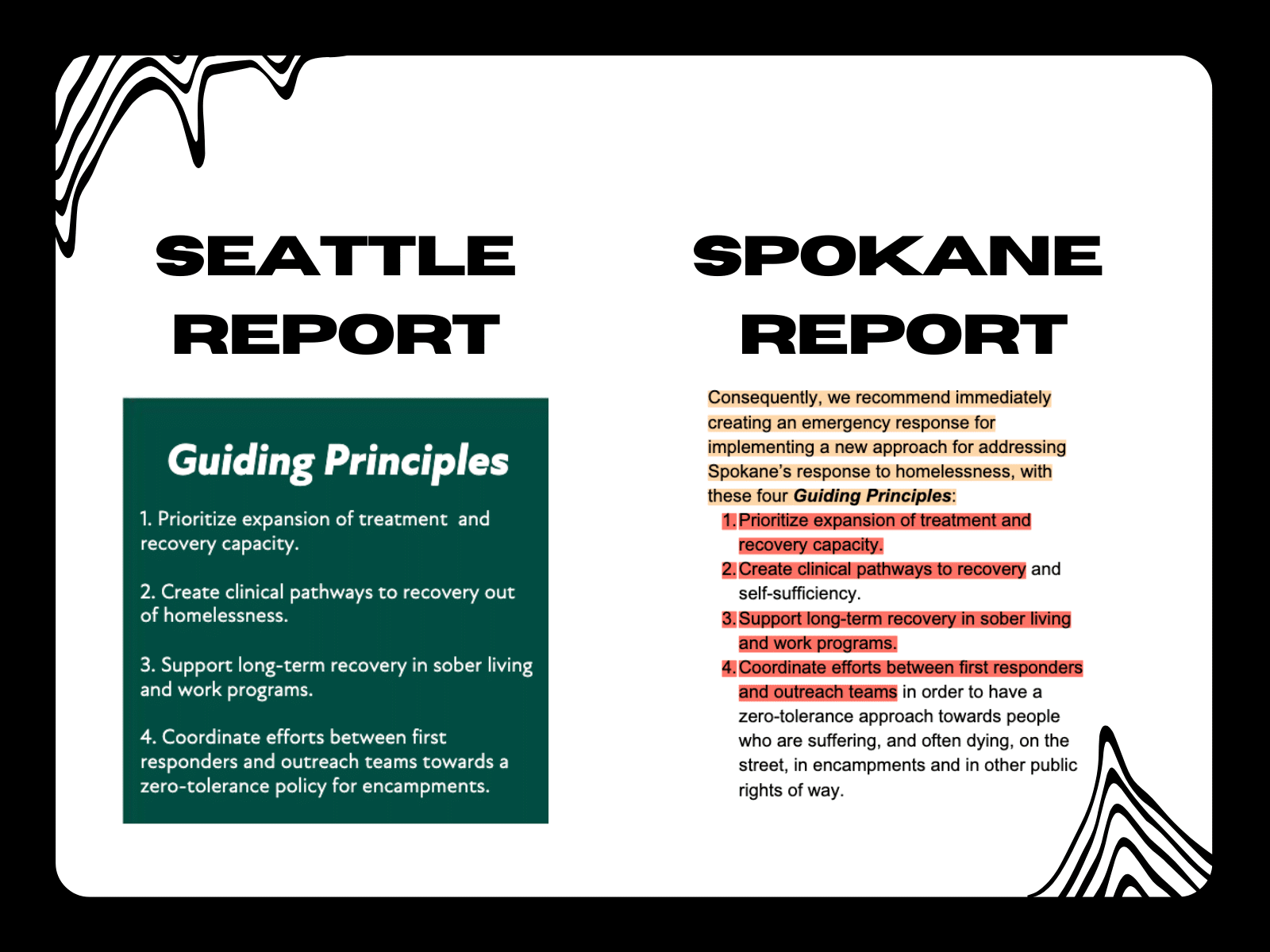

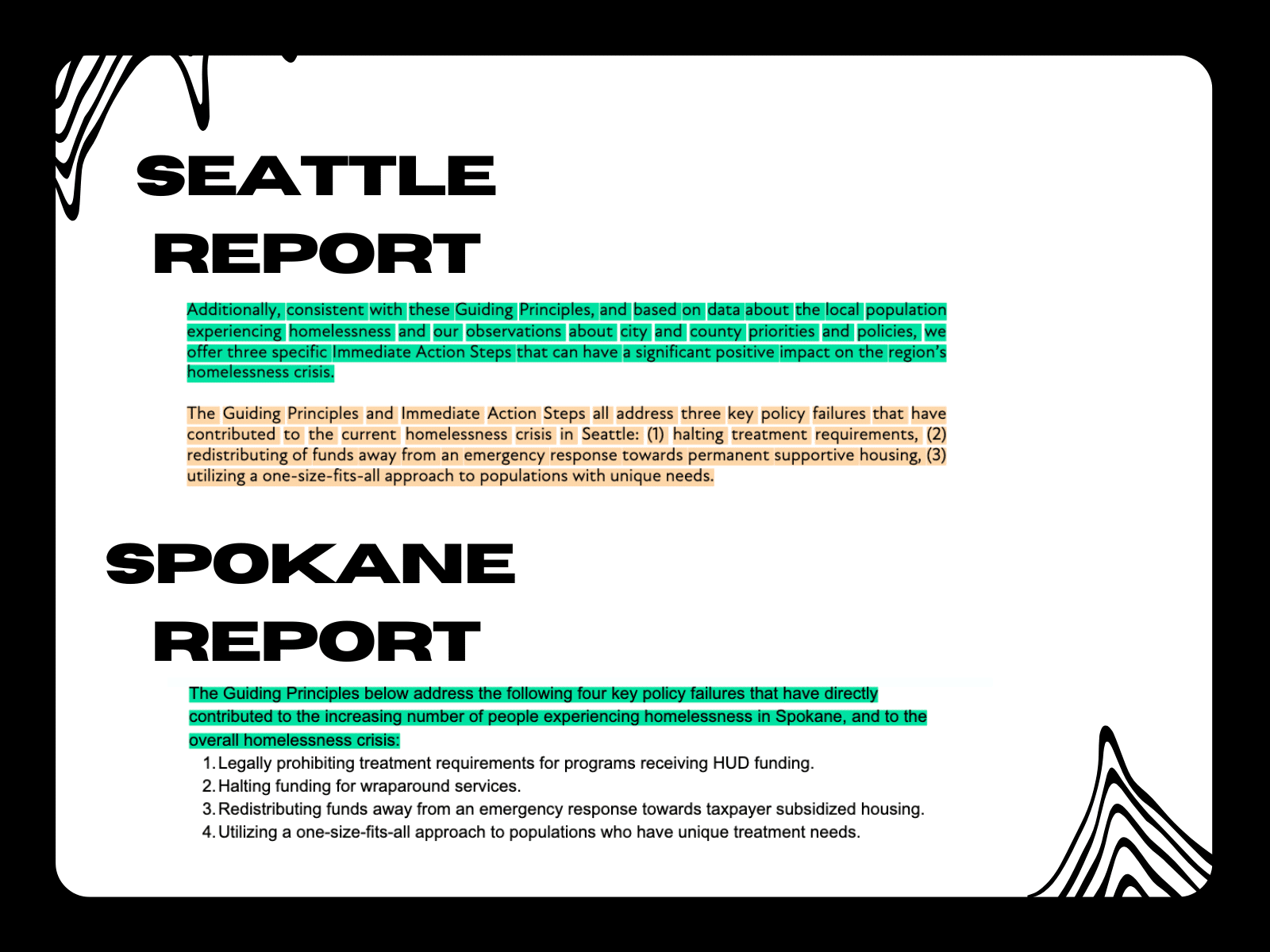

Both surveys proclaim that the city’s “homelessness crisis is one of the worst in the nation,” with no citations. Both surveys have the same guiding principles, nearly word for word. And both surveys have nearly identical policy recommendations for how each city should handle its crisis.

FLIP THROUGH THE GALLERY BELOW TO SEE SOME OF THE IDENTICAL AND MOST SUBSTANTIVELY SIMILAR SECTIONS:

Both surveys contain the key finding that most of each city’s homelessness population is not from there, and the recommendation that they should split responses into two tracks:

- One for “Individuals with direct connections to Spokane should receive long-term treatment services to successfully transition out of homelessness and be provided with continued support for sustainable recovery, housing and employment.”

- One for: “Visitors with no direct connection to Spokane should receive immediate and robust case management for family reunification in order to enable the highest chances of successful recovery and transition out of homelessness by being in close proximity to their longstanding support network. A priority focus should be placed on those who have been in Spokane for fewer than 90 days.”

Many in Spokane would balk at conflating both the problems and potential solutions in Seattle with those in Spokane. In fact, during her first campaign for mayor, Nadine Woodward vocally called for homegrown, “Spokane Solutions.”

Marbut, though, said the similarities were intentional. Here’s his response to this question, in full:

“Purposeful - Seattle and Spokane have very similar problems and issues that must be solved - best practices should be followed - focus on the data - Spokane is different.”

We asked SBA a few months ago how much it cost to have Marbut conduct the survey, and Cooley then declined to comment. We asked Marbut how much SBA paid him — he stopped answering our texts.

The end of the story

Though it has become more frequent, city spokesperson Erin Hut says she began hearing the story about homeless people from outside Spokane draining the city’s resources far before she started working in Brown’s administration.

“There has been this long-time narrative that folks who are experiencing homelessness are not from here, and I think labeling people like that is kind of a weak excuse for ignoring your neighbors,” Hut said. “ It's really easy to vilify ‘others,’ but the reality is here, that people experiencing homelessness and our community are our family members. It's our friends, it's our coworkers, it's our neighbors.”

Since Brown took office, her administration has been focused on data-based responses to homelessness, Hut said, like transitioning the city away from the congregate Trent Shelter to a scattersite model where they can address the unique needs of specific populations, like domestic violence survivors or people with high medical needs.

Hut described SBA’s survey as “vague,” and “a cut and paste report that didn't actually look into the policies in place and the funding here in Spokane.”

“It's so dehumanizing. There are people who have struggles and we should all want best outcomes for people,” Hut said. “It doesn't need to be this back and forth of ‘I'm right, you're wrong.’ It should just be okay, what's the best outcome to serve the people in our community? But I guess that's too empathetic for a government official to say.”

Even Garcia, who has at times been vocally critical of Brown’s response to homelessness, thinks SBA’s survey and the narrative it portrays is counterproductive. She’d rather see business owners who want to help address homelessness in Spokane funnel their money into programs and service providers that are already doing the work.

“People like Gavin [Cooley, now director of strategic initiatives at SBA]: what is your end result? What are you looking to accomplish?” Garcia asked. “We could really use some help down here on the ground, so could you walk alongside homeless service providers and compliment their programs instead of just criticizing them or our city? Are the mayor’s plans perfect? No. But they’re better than they have been. We’re getting somewhere. We’re working towards a goal and it can’t be political all the time.”

Garcia says she would like to see work done to collect other data she thinks would be more useful in getting and keeping people housed.

“How about acquiring how many people got housed, and how much our housing inventory is lacking?” Garcia added. “That's the data we should give a shit about. Not where somebody was born. It is very, very, very much in line with how we treat immigrants.”