Twenty years ago, Tina Hammond’s future looked bright. She’d just graduated from Gonzaga University with a masters degree. She owned a home in Spokane, and her finances seemed in order.

“My life was really good,” Hammond said.

Then the 2008 recession hit. She couldn’t find work in her field and took a minimum wage job. In just a couple of years, she burned through her savings and her 401k, desperately trying to pay her mortgage.

In 2010, Hammond lost her home.

Over the following decade, she worked to stabilize her finances — by moving back in with her family. In 2019, her father died, leaving her an inheritance large enough to buy a manufactured home in a mobile home community for people aged 55 and older.

It was a victory, but short-lived: last year, Hammond was thrust back into financial insecurity when she was hit with a 12% increase in rent for the land beneath her home. Because Hammond is disabled with a fixed income, the extra $66 a month meant she had to make sacrifices.

“I ended up stopping my meds for three months, trying to figure out what I could do to make up that $66,” Hammond said. “After three months, I finally figured it out: I turned my heat off at night.”

In the last year, Hammond has become a vocal advocate for rent stabilization in Washington, pushing for legislators to pass House Bill 1217.

Here’s a quick rundown of what’s in the bill, after it passed the House and lawmakers gave concessions to Senate Republicans:

- Yearly rent hikes would be capped at 7% for most rental properties, and 5% for manufactured homes.

- The 5-to-7% rent raise cap wouldn’t apply to buildings less than 15 years old.

- The cap also wouldn’t apply to property owned by a nonprofit or by a public housing authority.

- Move-in fees and security deposits would be capped at equal to or less than the cost of one month’s rent for renters with no pets and the cost of two month’s rent for renters with pets.

- Landlords would be required to give tenants 90 days notice for any rent raise.

- Landlords would be able raise rent as much as they want in between tenants.

- The law will expire in 2045.

Passing the bill could be a slam dunk for legislators — a Cascade PBS poll showed 68% of Washington voters want rent stabilization. Still, Republican legislators are largely against it, and last year, a similar bill died in the Democrat-controlled Senate.

Critics of the bill point to studies on the impacts of rent control, some of which showed mixed results like reduced housing stock and poor maintenance by landlords. Other studies have also found that “beneficiaries of rent stabilization were 10% to 20% more likely to stay in their homes long-term.”

Statistically, though, it’s hard to make definitive claims about what rent stabilization would do in Washington, because much of the data looks at cities with rent control rather than stabilization.

Rent control vs. rent stabilization

Rent control sets a hard cap on how much a landlord can charge for a unit while rent stabilization typically sets a percentage cap for how much the rent can be raised annually. For example, a landlord of a rent-controlled apartment may never be able to rent it for more than $1,000, while the landlord of a rent-stabilized apartment could rent it for $1,000 one year, $1,070 the next, and under these rules, they could raise it to as much as they want in between tenants.

The stabilization policy is also applied more broadly — with the exceptions carved out for new construction and nonprofit-owned buildings — so it’s possible that renters will be able to enjoy the positive impacts of rent stabilization without the negative counterbalances, like landlord jacking up rent in non-rent controlled apartments or turning rental units into condos to sell.

For local housing advocates, HB 1217 looks like a common-sense tool to keep people in their housing.

“I hear tenants’ stories every day. I see the pain of families separated because they cannot afford their apartment or rental home. Something needs to change,” said Terri Anderson, the interim Executive Director of Tenants Union of Washington State. “Tenants in Washington need to have predictable rent increases, and this bill will provide that for tenants and it will extend the notice period as well, giving tenants a little more time.”

In some ways, Spokane is ahead of the curve. Last year, the Spokane City Council passed an ordinance requiring landlords to give 180 days notice for any rent hike more than 3% to give tenants enough time to prepare for increased costs. But because state law prevents the city from implementing rent control or stabilization policies, they’re reliant on the state to make the call: can landlords raise rent more than 7% a year?

Last year, Senate Democrats killed an extremely similar rent stabilization bill, but this year, local advocates think the chances of the bill passing are higher: two vocal Democrat holdouts on the bill did not run for reelection. One of them, Sen. Kevin Van De Wege (D-24), was replaced by Sen. Mike Chapman, who was a sponsor on the Senate rent stabilization bill.

Currently, rent stabilization has passed the House and sits in the Senate, where it passed some big hurdles: this week, it cleared the Ways and Means Committee and moved to the Rules Committee, where it’s been placed on second reading. The Rules Committee will decide if the bill gets scheduled for debate on the full floor.

The numbers are in: it’s a bad time + place to be a renter.

Rent-burdened

By 2023, 50.3% of Washington renters spent more than 30% of their monthly income on housing costs — which is the threshold the state uses to determine if a person is “rent-burdened.” In Spokane, that number was even higher: 52.1% of renters were rent-burdened, and 28.3% of renters paid more than 50% of their monthly income on housing costs.

When you look closer at income, the housing landscape in the state gets even worse: to afford a one-bedroom apartment at the fair market rate, a Washington renter earning the minimum wage would have to work 83 hours per week.

And there’s a volatility to the market that can leave renters stranded with little notice.

“Tenants do not understand why they can get a rent increase that literally doubles the amount of rent that they pay,” Anderson said. “It is not uncommon in Spokane or anywhere across the state for a tenant to get a $400 rent increase and that they have to pay in 60 days.”

“ We're all told that if you work hard enough, that you can afford a place to live,” Spokane City Council Member Paul Dillon said at a recent press conference for rent stabilization. “But now if you're making minimum wage, you're told, ‘good luck.’”

High eviction rates

Though having to endure the cold Spokane winters without the heat on isn’t exactly how we’d define “lucky,” many renters haven’t been as lucky as Hammond, who is still in her housing.

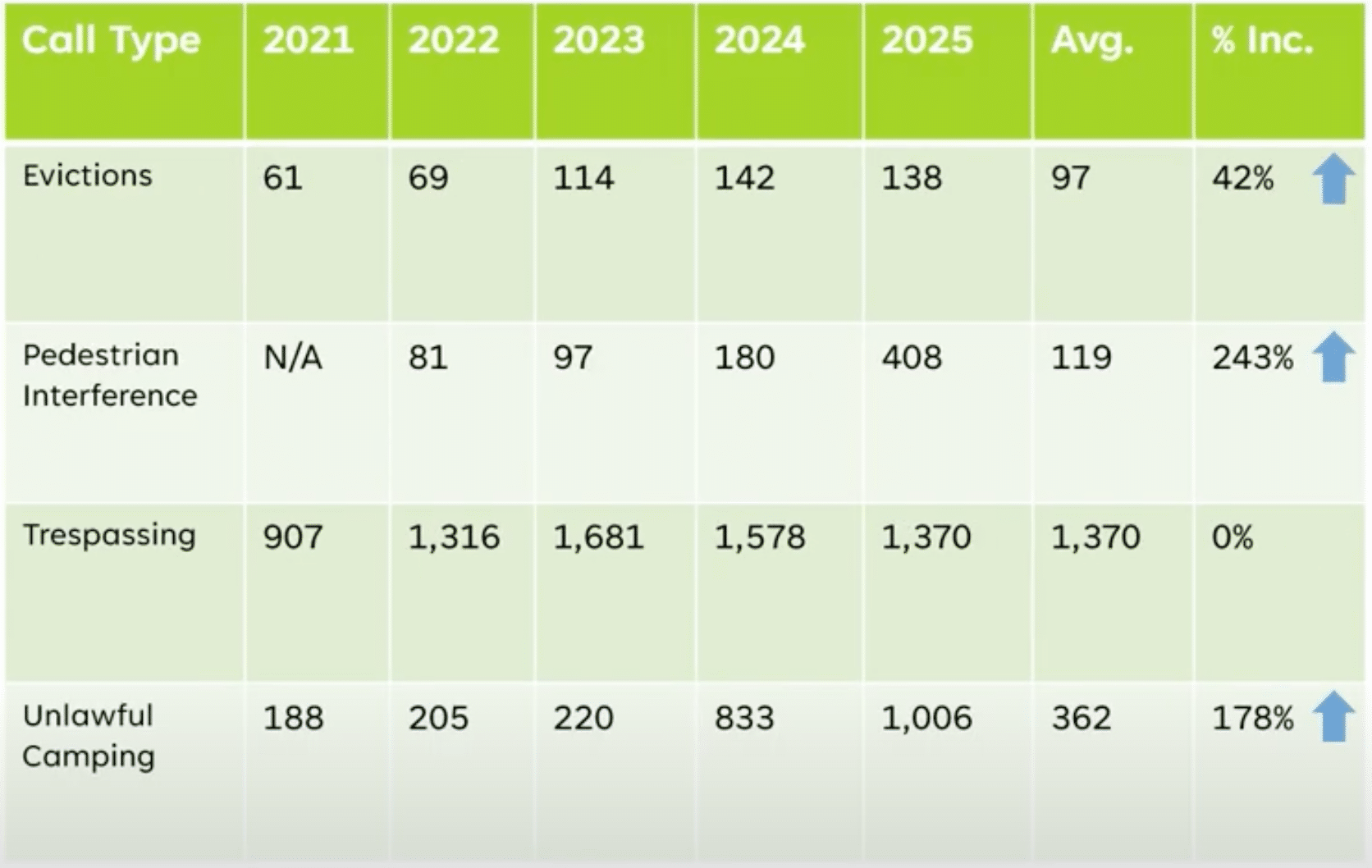

According to statistics from the Spokane Police Department (SPD), in the first three months of 2023, when 52.1% of Spokane renters were rent-burdened, SPD received 114 calls for their officers to assist with evictions. In the first three months of 2025, they’ve already received 138 calls for evictions, more than a 20% increase.

According to eviction defense lawyers and landlord resource groups, the most common cause across the state for eviction is failure to pay rent.

The people who are getting evicted are much different than the picture painted by landlords of “felons with fentanyl,” said Hannah Swenson, the managing attorney for the Spokane branch of the Housing Justice Project.

“It’s much bigger than that. It’s an economic issue. Rent is going way up. People’s costs and what they’re making are not matching,” Swenson said. “There are always going to be problematic people in a system, but there’s also single moms with two kids who are being evicted over one month of rent. There are disabled vets who haven’t gotten connected with community resources.”

In the last year, Swenson and her office of two to three attorneys — which is one of two “right-to-counsel” firms in Spokane — have represented more than 630 households in eviction cases.

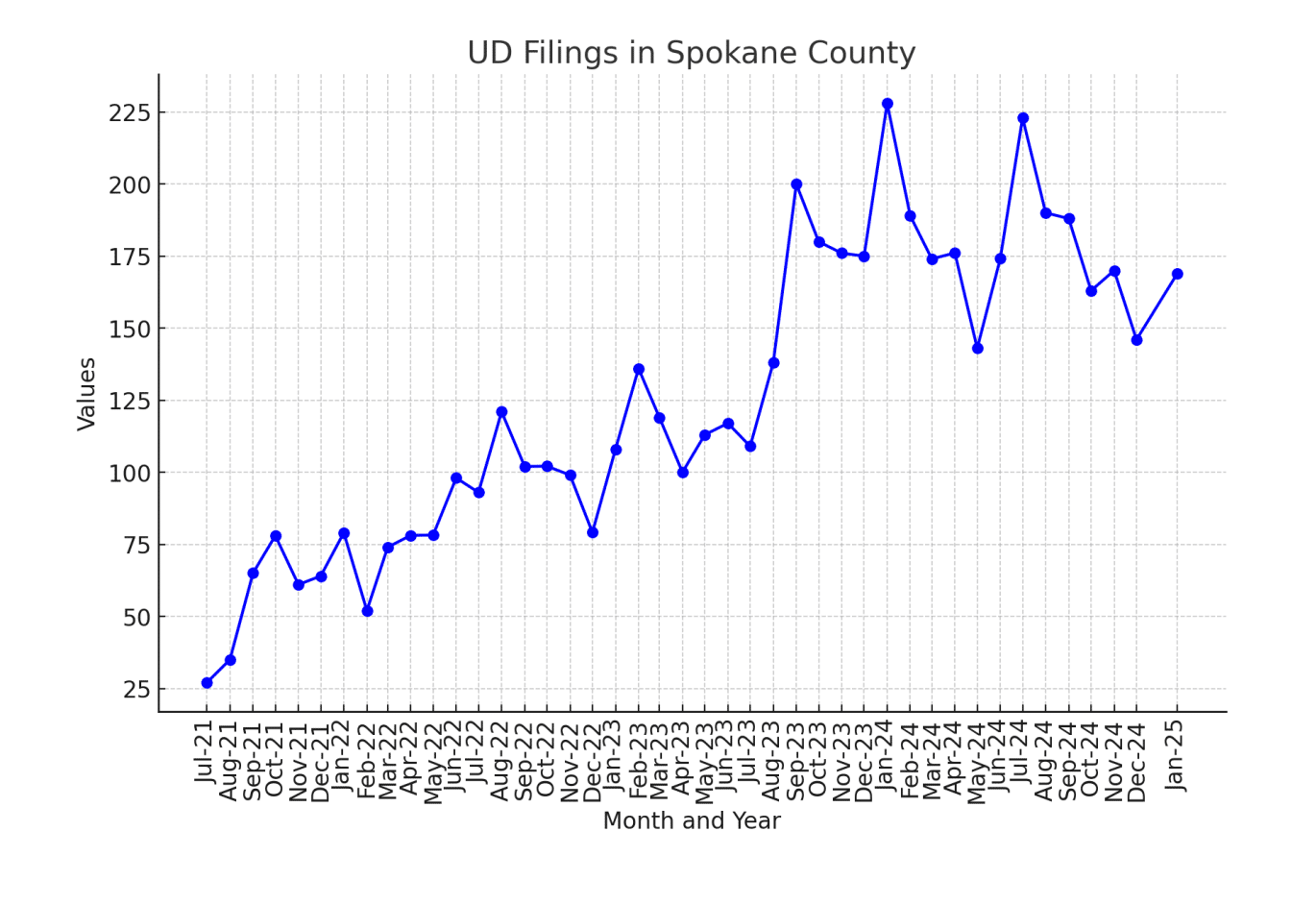

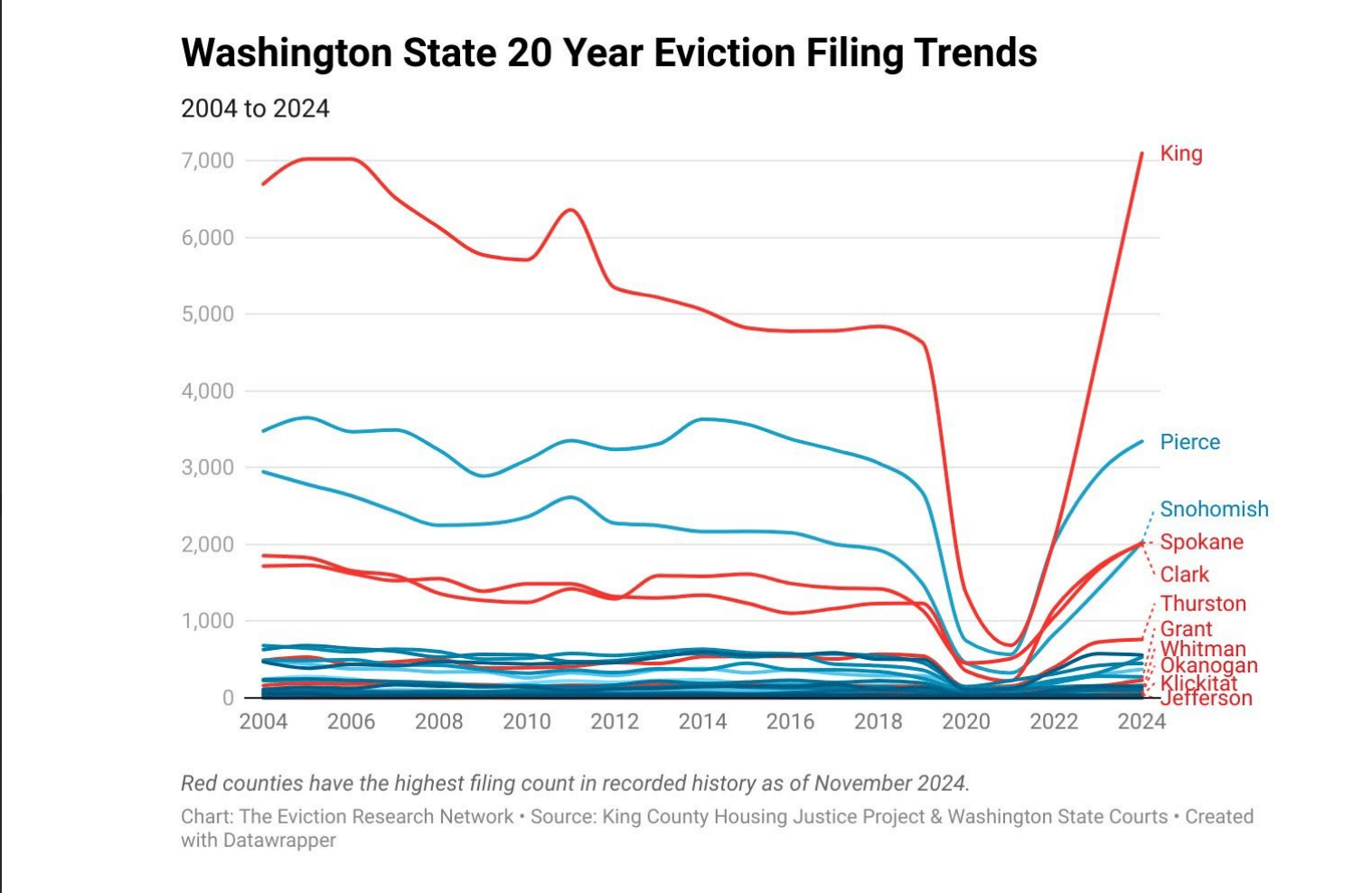

More data Swenson shared showed that it’s not just an anecdotal spike: eviction filings both in Spokane and across the state are at an all-time high.

While the numbers are bleak, it’s the human element that Swenson thinks about most.

“ Could you move out in three days? Where would you go? What would you do with your things?” she said. “ No one knows what to do with packing up their entire life and having a sheriff throw it in garbage bags and put it on the side of the road.”

Low housing stock

If someone is evicted because they can’t afford rent, they may have nowhere to to go because there isn’t much available housing close by.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Spokane County’s apartment vacancy rate hit an all-time low of 0.5%, which meant just 0.5% of all apartments in the city were available to rent. Those low vacancy rates caused the price of housing in the region to spike.

Since then, there has been an intense bipartisan effort from the Spokane City Council to increase available housing by incentivizing middle housing development, encouraging density around transit lines, repealing parking mandates and rolling back restrictions hindering new housing construction, like those that had previously made duplexes in residential areas illegal.

Most recently, the city council passed an interim ordinance to do away with height restrictions downtown, with unanimous bipartisan support: it was a longtime wishlist item for conservative council member Jonathan Bingle that was recently backed by progressive Mayor Lisa Brown.

Projections are showing these efforts are working: near the end of 2024, vacancy rates for apartments in the county were up to 5.8%, which puts a little more power in the hands of renters.

At the same time, though, projections from the 2025 Land Capacity Analysis revealed the city is expected to grow by more than 23,000 people in the next 20 years. To accommodate that growth — and house those who are currently unhoused — an estimated 22,359 housing units will need to be constructed. In the county as a whole, more than 53,000 units will be needed to house an estimated 110,000 people.

The good news is that Spokane city likely has enough available land to accommodate the growth within its boundaries. The bad news is that the county might not: preliminary estimates showed that the land available could only accommodate about three-quarters of the growth.

High demand and low unit availability would result in low vacancy rates again and, likely, skyrocketing rents.

The homelessness crisis

With the cost of rent rising much faster than the median paycheck in Washington, an unexpected rent hike can lead to evictions and even homelessness, if there’s no available affordable units.

According to the 2024 Longitudinal Systems Analysis published by the city, 7,221 people used homelessness services in Spokane, like emergency sheltering, transitional housing, rapid rehousing or supportive housing, showing a high need for services.

It’s not immediately clear in the city’s homelessness data exactly how and why people accessing services became homeless, but nationwide, the answer is largely economic: when wages don’t increase with housing costs, people are priced out of housing. Anecdotally, that’s what’s happening in Spokane. Most of the unhoused people interviewed by RANGE in the last year said they lost housing after losing a job or a major economic crisis, like hospital bills following a car crash.

Housing voucher programs, which historically have a high success rate of helping people exit or stay out of homelessness, can help fill some of those gaps, but the funding has been in flux since late 2024. And even before that, the city estimated there was only enough public rental assistance to help about one of four extremely low-income households

“ Since taking office last year I've heard the pain from constituents who reach out for rental assistance funds that are not there,” Dillon said. “This is a crisis and if we do not address rents, this crisis will continue to worsen.”

Rent stabilization would not only protect renters, Dillon said — it could also address community safety concerns, especially for people who see visible homeless people downtown as a sign of blight, danger or crime.

“ There are a lot of people in the city who want to arrest our way out of this crisis, while also opposing policies like rent stabilization,” Dillon said. “The truth is this: it's not just people experiencing homelessness, it's people who can't afford rent. I hope that we can pass rent stabilization to keep people in their homes.”

“The safest communities have the most resources where people can rest their head at night,” he added.

If you want to provide comments on the rent stabilization bill, you can do that here!