Why I wrote this.

I grew up queer and closeted in small town Idaho. All through high school, I heard fellow students say horrible things about people like me. A girl in my class was teased because her older brother had come out as gay after graduating and moved to Seattle. The first and only time I tried to explore my sexuality in Idaho, I was cornered in a bathroom a week later by an older girl on my basketball team and asked aggressively, “Are you a lesbian?” I told her the truth: no, I wasn’t. But I was bisexual, and it wasn’t until I moved to Washington for college that I felt safe enough to come out and explore my identity.

When I would go back to visit my family, I noticed something interesting: Idaho was seemingly becoming more open to queerness. My younger brother told me there were a few students in high school who were dating, and out as lesbians. I attended a street festival and saw not only queer people out and about, but allies, too, wearing shirts in support of their LGBTQ+ friends, family and neighbors.

As queerness was becoming more and more visible in public spaces, the state’s politics were getting more and more aggressive against them. I never moved back to Idaho, instead choosing to make Spokane my home, but I wondered about the people who stayed: the people work to hold safe Pride festivals in Coeur d’Alene. The saphhic couple holding hands at Lewiston’s Dogwood Festival. The trans advocates fighting anti-queer legislation down at the statehouse in Boise.

As Valerie Osier always tells me, there is nothing more powerful than a reporter’s curiosity. So I’m proud to share the stories of the queer Idahoans who stayed, who still call the state their home.

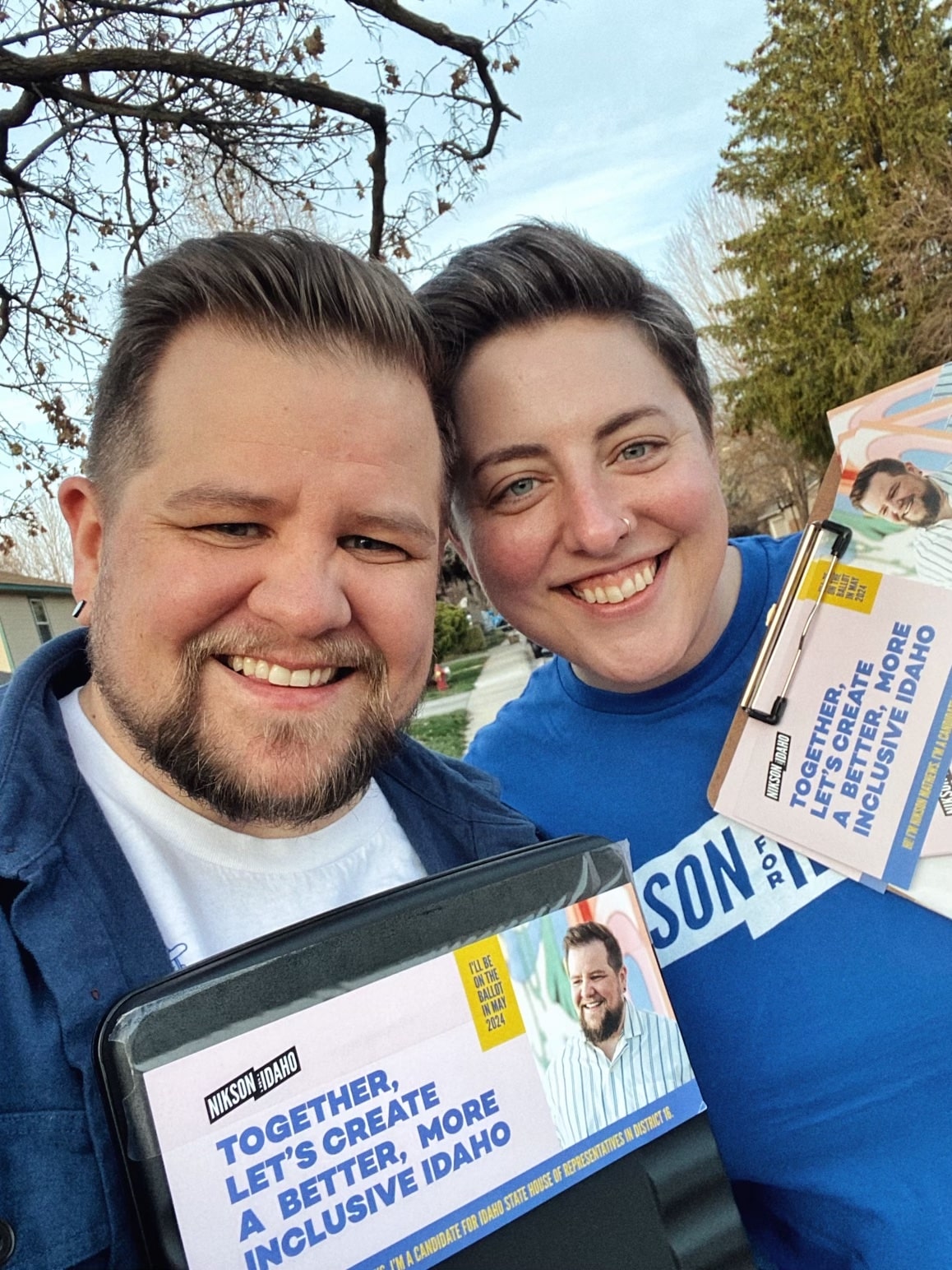

Though he was born and raised in Idaho, it wasn’t until Nikson Mathews left, moved back and ran for elected office in 2024 that he fell in love with the state of his birth.

Mathews, whose family has been in Idaho for generations, left nine years ago. “The closest people in my life were supportive of me,” Mathews, “but after I came out as trans, I definitely had negative experiences.” Those experiences, he said, led to a lot of fear, and the fear wore him down emotionally. “I was always paying attention to the exits,” he said, “It’s tiring to have to be so aware of everything around you.”

He moved to Seattle and stayed for six years. While there, he met his partner. He found his true self. He breathed a little easier. But something was missing — Mathews missed home.

He missed Idaho.

Like Mathews, Nat Elkins was born and raised in Idaho, too — the state that had also been home to their family for generations.

Unlike Mathews, Elkins never left. Why would they?

“I love this place. My family is here. I’ve swam in the rivers, I’ve climbed the mountains,” Elkins said. “This is my home.”

For 23 years, Elkins was an Idahoan like anyone else. Then, they came out as queer, and “suddenly, I’m looked at as an outsider,” they said.

Mathews and Elkins are two of the approximately 48,000 queer people who call Idaho home, according to data collected in 2020. The number of LGBTQ+ Idahoans has risen sharply, up from 31,800 people in 2017 — a growth of nearly 50% in just three years.

As the queer community in the state has grown and become more visible, so has overall social acceptance. In 2014, only 49% of Idahoans supported same-sex marriage. In 2017, that number had grown to 56%, and by 2019, 71% of Idahoans also believed there should be nondiscrimination laws to protect LGBTQ+ people in their state. There has been an increase in Pride celebrations in smaller, more rural communities, with places like Sandpoint, Rexburg, Silver Valley and Sun Valley holding their first Pride celebrations in the last four years.

But as Idaho’s queer community and general social acceptance of them have grown, so has public antagonism from political figures and the tally of discriminatory laws, noticeably ramping up in 2020.

Take Action – Organizations to know and support

Sandpoint Alliance for Equality (SAFE): a Pride-inspired nonprofit in Sandpoint, Idaho, led by LGBTQIA+ people to turn Pride, safety and belonging into a year-round experience

North Idaho Pride Alliance (NIPA): a nonprofit organization of LGBTQIA+ people, allies and community groups working together to create a more inclusive North Idaho

Allies Linked for the Prevention of HIV and AIDS (ALPHA): a nonprofit providing a safe and welcoming place for HIV and AIDS education, testing and support in Idaho

Southern Idaho Pride (SIP): a Twin Falls, Idaho-based nonprofit providing spaces for celebration, opportunities for education and resources in partnership with community connections for the LGBTQIA+ community

Add the Words, Idaho: an Idaho lobbying group fighting for justice for queer Idahoans that also hosts actions and does mutual aid work.

Pride Foundation Idaho: a Boise-based foundation that partners with local organizations to support queer Idahoans across the state

The Community Center: a community center in Boise providing a safe and welcoming space for queer people.

Inland Oasis: a nonprofit providing support to the LGBTQ+ Community and Allies on the Palouse.

Idaho Falls Pride: a nonprofit hosting Pride events in Idaho Falls

Flourish Point: a nonprofit helping LGBTQ+ people in Rexburg access access compassionate, evidence-based, accessible and affordable mental health care and support services. It also hosts Rexburg Pride.

Boise Pride Fest: the nonprofit that hosts Boise’s Pride Fest.

Rainbow Circle Idaho: an organization helping Idaho LGBTQIA2S+ people access mental health care.

Reading Time with the Queens: an organization creating educational programming for kids, hosted by drag queens, in Pocatello and Idaho Falls

If you live in Idaho, you can also contact your local and state legislators to tell them what’s important to you! Find your state legislators and their contact info here. If you live in Idaho, you can also register to vote — more info on how to do that here.

‘Looking over your shoulder’

Idaho finished out their 2024 legislative session in April by passing three laws targeting LGBTQ+ Idahoans: House Bill 668, which banned any public funds, including Medicaid, from covering gender-affirming care; House Bill 421, which defined gender as the same thing as biological sex and House Bill 538, which requires educators to call students by their legal names unless they receive written permission from students’ parents to use anything different. The state also passed a bill requiring libraries to get parental signatures before allowing minors to check out “harmful materials,” which is vaguely worded, but likely includes queer literature. In all, the legislature proposed 19 pieces of legislation that would negatively impact queer and trans people, and passed seven of them.

Two anti-LGBTQ+ laws were defeated: a bill that would have banned any instruction on “human sexuality, sexual orientation, and gender identity prior to grade 5,” and a bill that would have given religious exemptions to discrimination against queer people.

But the year before, Idaho passed a law banning gender-affirming care for minors, including puberty blockers and hormone therapy, and in 2020, passed laws banning transgender women and girls from competing in sports in the state, and forbidding people from changing their gender markers on birth certificates.

The state also allows conversion therapy, even for minors.

This is in keeping with a broader shift in Idaho politics to the far right in the last three decades, which has also seen an even more visible and drastic change in the last five years — driven by statewide organizations like the Idaho Freedom Foundation, nationwide interest groups like the far-right Christian organization Alliance Defending Freedom, and private hate groups, both local and national, like Patriot Front, which attempted to storm a 2023 Coeur d’Alene Pride celebration.

National forces (and funders) often work within state organizations. The Idaho Family Policy Center, which only started in 2022, registers itself on federal records as “a non-profit ministry … promoting biblically sound public policy … and training statesmen to advocate for Judeo-Christian values,” and lists national partners like Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council on its website. The group has quickly become a major driver of policies that make the state increasingly unfriendly for the queer Idahoans that call it home, starting with a 2022 attempt to ban drag performances in public space. They drafted the bill that limited Idahoans’ access to literature with BIPOC and LGBTQ+ characters, which was passed during the 2024 legislative session and took effect July 1.

The people RANGE interviewed say these policies have real consequences for queer people. As these bills have taken effect, a peer-reviewed study tracking suicides by trans youth from 2018 to 2022 found that states that have passed anti-trans laws have seen a 72% increase in suicide attempts by trans youth compared to states with no such law. This has led to a staggering statistic: in 2022 alone, 27% of trans and nonbinary youth in Idaho reported having attempted suicide, compared with 15% of trans and nonbinary youth in Washington state.

More recent data isn’t available yet, but as Idaho has passed even more restrictive laws since 2022, it seems likely that number has risen even more.

In the middle of all this upheaval, Nat Elkins was working as an on-air news reporter in Boise with a promising career ahead of them. When they came out about three years ago, the consequences of being queer in Idaho were clear and immediate.

As they started to explore their gender identity and present in ways that were less feminine, like wearing a suit on air, they began to get comments in their inbox about how they were too masculine. Off camera, it changed how they were able to move through the streets of the city they’d called home their whole life.

“I cut my hair off and I hold hands with my girlfriend walking down the street and suddenly, I’m looked at like an outsider,” Elkins said. “I’m not getting spit on every time I go outside, but you can feel the energy: it’s different … there’s this sense of otherness.”

Shortly after coming out, they decided to move from an on camera reporting job to a behind-the-scenes producer role, in part due to the backlash they were receiving about their gender presentation. Within a couple years, they had left the industry altogether, citing burnout.

As they began to further explore their trans identity through drag, Idaho became even more dangerous.

Elkins, who now performs under the drag name Buck D’Licious — which RANGE will be using to refer to them as for the remainder of the story — was excited to go to their first Pride in drag. It was not only their first Pride with their new persona, it was also one of their first times out in public dressed in drag, and they were doing it with their partner.

“We were drag babies,” D’Licious said.

As they walked down the street, people threw things at the couple from the top of a parking garage. “They were trying to dump their drinks on us, spitting at us,” D’Licious said. Then, it got worse.

“This big truck packed full of guys stopped at a parking lot in front of us,” D’Licious said. “They were screaming slurs at us. One of them got out [of the truck].”

D’Licious felt the fear rise, worried “they were going to beat the heck out of us,” but when D’Licious made it clear they were ready for a fight and would defend their partner, the man decided to get back in the truck.

“It was very scary.”

It also wasn’t an isolated incident. After leaving journalism, D’Licious worked security at one of the gay bars in Boise, and routinely had to stop “hateful people” — some carrying weapons, some making threatening remarks — from entering the bar. “There’s definitely a sense of constantly looking over your shoulder as a queer person in Idaho,” D’Licious said.

Despite the fear, D’Licious isn’t ready to give up on Idaho.

“I love this place just as much as everybody else. I have lived my whole life here,” D’Licious said. “Why should I be forced out?”

‘Why not me?’

As D’Licious was contending with the realities of coming out in Idaho, Nikson Mathews was contemplating moving back to his home state.

He told RANGE he had a sense of both the statistics and stories, and once he brought up the idea of moving back to his partner, it resulted in multiple deep conversations about what the move would mean for the two of them, as a couple. They feared the consequences that might come with living in Idaho, like losing access to the protections and safety they enjoyed in Seattle.

To all of this, Mathews says his partner was open, but cautious. The question, though, was never to either continue living openly in Seattle or try to quietly exist under the radar in Idaho.

Ultimately, “we made the move,” Mathews said. “But we made a promise that we would get involved and try to make things better for folks in Idaho.”

Choosing to move also meant choosing to fight.

“This is our home. We shouldn’t have to leave,” Mathews said. “We have family here. We have roots here. We have jobs here. We want to save our state. We want our state to be our home, and we don’t want to leave folks behind.”

Across the state, queer people are making similar decisions, and over the next few months, RANGE will be telling stories of queer people across Idaho and the many ways they fight to stay connected to their home while, in their words, fighting for the soul of the place itself.

We spoke with Jeff Samson, a drag queen and a chief financial officer living in North Idaho, who focuses on making connections with his neighbors, answering questions and being a voice for queer people in spaces that might historically be unfriendly, uninformed or risky.

We talked to Brandon Connelly, the president of Southern Idaho Pride, who balanced political involvement with organizing work until it felt like organizing for his immediate community needed all of his focus.

We heard stories from Joseph Crupper, aka Miss Cali Je, who started Reading Time with Queens in 2017, a nonprofit that hosts reading, crafts and American sign language learning events that has been under fire, mainly from religious transplants to the state, since 2023.

We interviewed Avery Rae from Twin Falls who, for a time, was the only drag king in the city and who uses his art as a form of queer joy and resistance.

We spoke with Bonnie Violet Quintana, the trans drag performer and “digital chaplain” who founded ALPHA, an organization providing AIDS and HIV prevention education and serving HIV positive individuals in Idaho, and who threw Idaho’s first Trans March in September of this year.

For D’Licious, fighting for Idaho looks like speaking out, performing in drag and visibly staking their claim on their home.

For Mathews, who is now a lobbyist with advocacy organization Add the Words, Idaho, chairs the newly reformed Idaho Democrats’ Queer Caucus and ran his first campaign for office this year, it looks like fighting in the arena of politics.

“I was waiting for somebody to run. We need representation,” Mathews said. “And then it just kind of shifted and it became — why not me?”

For each and every queer person in Idaho, the fight looks different, Mathews said. Some people bring their talents to fundraising or distributing resources, others to creating spaces of queer joy and resistance. Sometimes, it’s leaving, fighting for the state from beyond its borders, and coming back when you’ve found yourself. Sometimes, just surviving is all someone can do to carve out their corner of Idaho.

But while Mathews and his partner thought they might be losing something by leaving Seattle — with its large, vibrant and inclusive community — they’ve actually found deeper connection in Idaho.

“I’ve never felt a closeness within a queer community like I have here,” Mathews said. “There’s a very real sense of danger, but there is also a stronger sense of queer community and taking care of each other.”

Join the discussion on Reddit: r/Spokane and r/Idaho

Queer in idaho? Tell us your story!

Email erin@rangemedia.co