Two years ago, Renata went to the Spokane County Superior Court seeking a protection order against her abuser. That day at the courthouse, no one was available to speak to her in Spanish. Instead, she was handed a flier for Mujeres in Action (MiA), a local nonprofit that advocates for survivors of domestic violence. (At her request, RANGE is only using Renata’s first name to protect her identity as a survivor of domestic violence.)

Before she was connected to MiA, Renata said she felt like she was all alone, trying to protect herself while navigating an unfamiliar system in a country where she couldn’t speak the language. “If I didn't know about MiA — because someone helped me to know about MiA — I would never go to the court and do something about it,” said Renata, who speaks English well now. “Because, you step in the court and nobody's able to help you if you don't know English.”

Even after she got a protection order and a court date with the help of advocates from MiA, she still felt like the system wasn’t fair. During one hearing, the interpreter provided to her by the court was a friend of her abuser. “I was not comfortable with that,” Renata said. “I didn't know English, I didn't know what she's going to say.”

Even when she asked for a new court date and had a translator she trusted, it still wasn’t fair: each party had the same amount of time to state their case, so she could say half as much because all of her statements had to be translated.

That made an already challenging situation that much harder. “When you go to the court you are nervous, you have trauma, and even in your language, you're nervous and can feel like you don’t know what you're saying because you're so nervous,” she said.

Renata’s experience is indicative of the struggle many community members have when trying to access justice in Spokane’s criminal legal system — which is largely run by Spokane County — and throughout the rest of county government. It’s also a problem as Spokane continues to become more diverse. In Spokane County, 7.4% of residents — more than 40,000 people — speak a language other than English at home, according to census data. In Spokane County’s latest demographic information from 2022, more than 12,000 speak Spanish, more than 14,000 speak what the census designates as “Other Indo-European languages”, over 9,000 speak Asian and Pacific Islander languages and just over 4,600 speak other languages at home.

As an organization that supports people like Renata, MiA is leading a community coalition of 16 local organizations pressing Spokane County to improve its language access services.

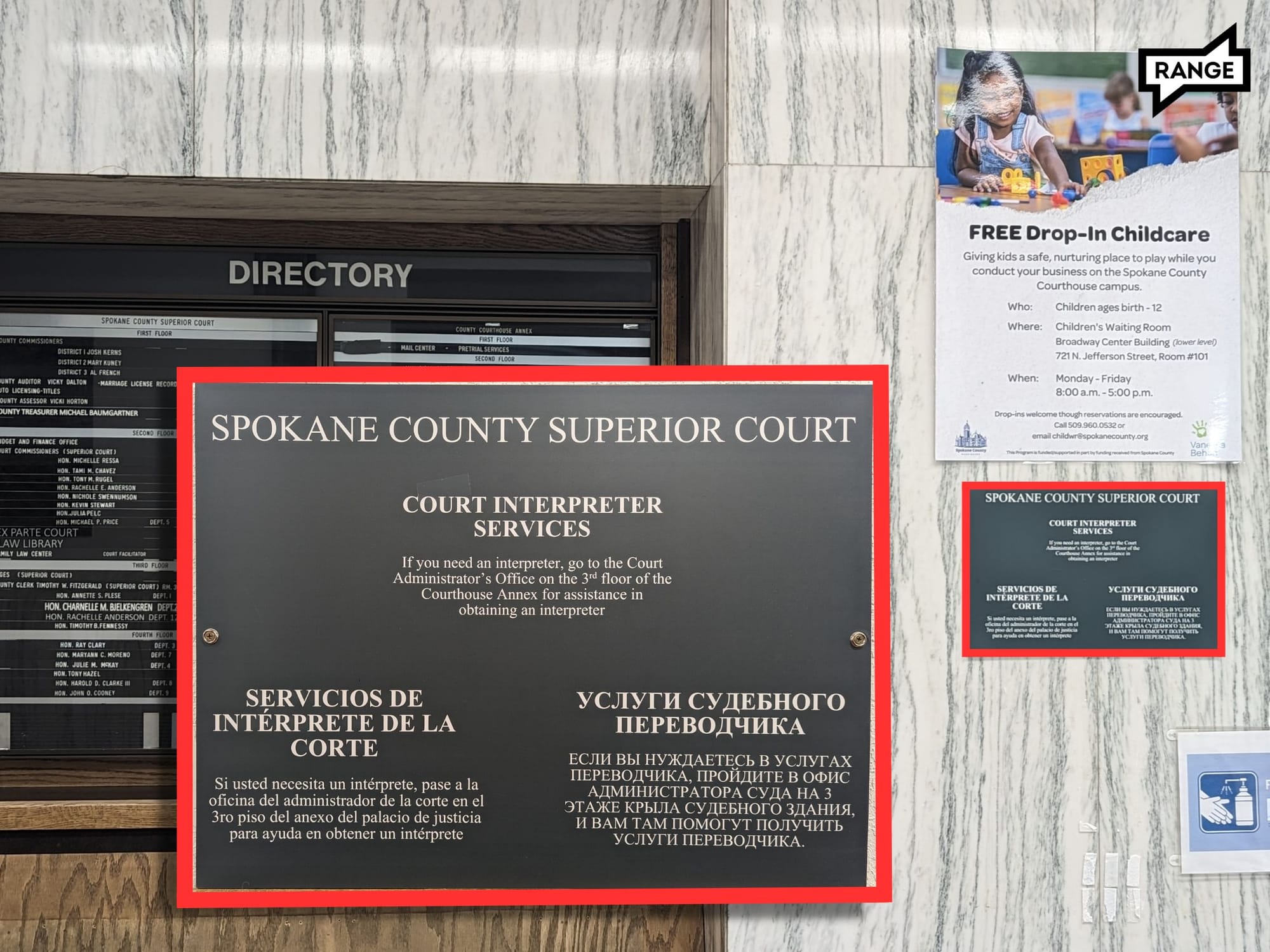

The policies that they’re advocating have been incorporated into federal law since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, although local municipalities often struggle to provide the full range of necessary translation and accessibility services despite requirements attached to federal funding. At the Spokane County courthouse, signs directing people to interpreter services are only written in Spanish and Russian. Since October of 2022, the majority of refugees resettled in Spokane have come from the Congo, Afghanistan and Syria. Spokane County also has the second largest Marshallese community in the United States. Current signage provides no clear way to request translation services for people from those four communities when they arrive at the county courthouse.

“As we were advocating for survivors and going through the systems — the police or courts or even hospitals — we started noticing these barriers of language access,” said Ana Trusty, the communications director for MiA. “Everyone says they have a plan for language access, but when we’re there, there’s no language access. People don’t know how to get the translator on the phone. They don’t think it’s important for that person to understand what’s happening with their body or their case.”

“We realized that we couldn't be there for each and every person that needed an advocate for them to have language access,” Trusty said.

Testing the system

Trusty, MiA’s Political Advocate Jesus Torres and Executive Director Hanncel Sanchez visited the county courthouse to experience the language barriers they’d heard about for themselves this March. Each of the trio speaks English, but they were only speaking Spanish that day. What they experienced was a frustrating reflection of the challenges faced by people seeking help in Spanish, let alone less frequently spoken languages in the community.

After making it through security, where Trusty had a pocket knife taken away after some hand gestures, Sanchez went to the clerk’s office “walking in the shoes of somebody needing to get a divorce,” she said. Torres and Trusty, who are familiar faces in the courthouse, hung back.

Speaking in Spanish, Sanchez said she asked the lady at the front desk for the papers for a divorce in Spanish. “She was freaking out. She didn't understand me, and she was just shaking her head [and saying] ‘sorry, I don't understand.’”

Eventually, Sanchez said she asked the clerk desk staff for an interpreter, which in Spanish is “intérprete.” Still flustered, the employee gave her information about protection orders printed in English then left her desk. “I didn't even know where she went, so I left,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez’s next stop was the court facilitator’s office. “When you go in there, there's a sign right outside the door that says one person at a time and it's in English,” Sanchez said, which limits the ability of people to bring a trusted person to translate. “We've had instances before where an advocate goes in with the survivor and they get yelled at by the front desk.”

Again, requests for an interpreter yielded no help. “I was asking for an interpreter and she's like, sorry, we don't have interpreters, you need to come back with somebody who speaks English so we can help you. I kept asking for an interpreter because I didn't understand what she was saying and she repeated the same thing. She’s just like, ‘sorry, I don't speak Spanish. You need to come back with somebody who speaks English.’”

Finally, Sanchez went to the interpreters office, despite no one directing her there for help. “At this point, I was not surprised at what was happening, but I could not help being disappointed.”

“I approached the lady in the interpreter's office. I asked her, ‘can I get an interpreter’ in Spanish and she was already freaking out. She started using hand signs to communicate, speaking slowly in English, and I was just trying to tell her: ‘I need information to get a divorce. Can I get an interpreter?’”

After about 15 minutes, and an attempt to communicate via Google Translate on the court employee’s phone, the employee grabbed a man in a suit who started speaking Spanish to Sanchez. His first question was more disheartening than the failed communication with the other staffers.

“I told him, ‘I'm just, I'm here to get some information for a divorce,’” Sanchez said. According to Sanchez the man, who she later learned works in the prosecutor’s office, responded: “Please don't take offense with this, but how did you enter the country?”

In part because immigration status can be used by abusers, immigrants who experience domestic violence have the legal right to a divorce and protection order regardless of their immigration status.

The state of Washington has also taken steps to prevent federal immigration officials from carrying out enforcement in local courts. In Washington state, federal immigration agents cannot arrest people at a courthouse without a warrant. When the bill passed, Gov. Jay Inslee said, “We do not want the increase in courthouse arrests from Immigration and Customs Enforcement to produce a chilling effect on someone getting access to justice.”

Sanchez, who is aware of these rights as a leader of an organization that seeks to protect people from domestic violence, was taken aback. “I did not respond to that question,” Sanchez said. “I just looked at him surprised. I could not believe that he was asking that question. I was freaking out. I'm documented, but when he asked me that, I got so nervous.”

“Then he said: ‘Did you get married here? Is he a citizen?’”

“I asked him: why were you asking me for my immigration status? And, he said, ‘It matters for how the divorce is going to go.’”

Then he offered to take her to the clerk’s office while advising her that she was going to need an attorney for her divorce. “That was really scary that he asked me how I entered the country,” Sanchez said. “If I was a survivor in an abusive situation trying to get a divorce, trying to get information on how to file for a divorce, that would put me in a situation where I would have to go back home and just get pretty much stuck there because the court just asked me for immigration status.”

“Turning people away because they don’t speak English is not serving justice. Survivors, regardless of their immigration status, regardless of nationality, race, gender, need access to the courts,” Sanchez said. “The Latinx community already doesn’t trust the justice system. For me, having this experience, walking in the shoes of a survivor, it is very frightening and disheartening and disappointing and frustrating.”

Cultural sensitivity in court

The difference between having language access in a culturally sensitive context and not makes a profound difference for survivors of domestic violence. For Adriana — who experienced psychological, verbal and sexual abuse in a previous relationship — not knowing how to speak English meant not knowing what rights she had or how to get help. (RANGE is only using Adriana’s first name to protect her identity as a survivor of domestic violence.)

“I think that not knowing the language makes us think that the laws are different and they're not for us,” Adriana said through an interpreter. Because of the fear factor involved with going to court, Adriana said that better translation services there are especially important. Before she found support from the advocates at MiA to help her, she felt lost. “The forms are only in English and that was hard to understand. And sometimes there was an interpreter available only for [her abuser] and not for me.”

Now, Adriana said, she has learned that she has rights that she was previously unaware of, and feels safe and empowered. “They basically helped me not feel alone and connected me with a lawyer and also resources and information about the processes that I was going through,” Adriana said. “Now, I feel that the laws are for all of us and that language doesn't matter. If you don't speak the language, the law still can be helpful and justice comes for everyone. There's people here to help and in this case it was MiA that was able to help me get there.”

One reason cultural sensitivity is of such high importance, in addition to language access, is the different roles police and the courts can play in other parts of the world. This is true for all immigrants and refugees, and especially for those fleeing repressive regimes and corruption.

Renata, a survivor of domestic violence, said “sometimes you're so afraid about the police, because in our countries the police are different. You are more afraid of the police than the other person,” Renata said. “So, you're just so nervous and you don't do anything about it.”

According to Annie Murphey, the executive director of the Spokane Regional Domestic Violence Coalition, Renata’s experience is common. “There tends to be a mistrust of law enforcement,” Murphey said, “as well as difficulty just understanding our complex laws and legal systems and where to go to get the resources that you need.”

The murder of an Iraqi woman by her ex-husband on Spokane’s South Hill in 2020 really drove home the complex issues and devastating consequences of systemic barriers to support survivors of domestic violence, Murphey said. “There were a lot of conversations across the system about how do we better support people that are non-English speakers, especially with some of these newer groups of people that have been coming to Spokane.”

Those conversations have led to a focus on the distinct needs of immigrant and refugee communities. “As we've worked with different groups that support immigrant and refugee communities that have come to the Spokane area, we've talked a lot about the stigma around domestic violence and cultural norms and the differences of the laws in the United States than in some of the countries of origin,” Murphey said. “There can be some social acceptance, so to speak, of violence and a lack of understanding of what the laws are here in the United States.”

Murphey said that improving language access is part of a broader suite of community support that can help survivors in immigrant and refugee communities. “The criminal justice system is extremely complicated. It's hard enough for people that speak English, let alone trying to understand something in a different language,” she said. “I think that we really need to work to improve that and it's not just language access. It's also offering culturally relevant services to people.”

Pushing for change

Since that day at the courthouse, MiA has been lobbying county officials and rallying people to their campaign for a community-wide language access plan. Sixteen organizations have signed on in support so far, and MiA has been meeting with county elected officials to drum up support for improved language access.

Over the course of the last month, community members have addressed the county commissioners in Arabic and Spanish and asked for action on behalf of Spokane’s diverse communities.

MiA said that talks with county staff have generally been productive, but they’re looking for leadership from the county commissioners to make systemic changes to improve language access. One of the challenges is that unlike the city, where the mayor’s administration oversees practically all city employees, the county has a whole spate of elected officials with oversight over their own offices, like the county clerk, auditor, assessor and sheriff.

The pitch, according to Torres, MiA’s policy advocate, is: “Hey, wouldn't it be easier if the county just had one plan, one set of directions, one set of rules, and one person who is either designated or hired as the language access coordinator for the county?”

That kind of coordination, and funding to support the changes, would require action from the county commissioners, who serve as the legislative body of the county and hold the purse strings.

County commissioner Chris Jordan said he’s been working on the issue with advocates from MiA, and supports a broad language access plan for all county services. “I really think it needs to be a countywide policy, and it should include the courts and the clerk, but go beyond that to every customer facing department,” Jordan said. “So that would include folks who come to get a marriage license or an auto license or pay taxes or have questions about their property assessments.

Commission chair Mary Kuney was less enthusiastic in her response to questions about the ongoing campaign for language access. “I have met with members of MiA and there is ongoing dialogue between all parties involved,” Kuney said in an emailed statement to RANGE. “There are many factors to consider and the discovery process has begun.”

Jordan said that a comprehensive language access plan is key to improving services not just for the community but increasing the efficiency of county government. “I really think we need more resources for all of those customer facing departments,” Jordan said. “I see it as an access to justice and access to services issue, but I also think it's an efficiency and kind of good government issue.”

“I know that when folks come to apply for a marriage license or an auto license and they don't speak English, they're basically not able to be helped.” Jordan said, “Sometimes they come back two or three times with friends who might be able to help them understand what's going on. And that takes a lot of staff time as well. So, I really think it's a win-win.”

But Jordan acknowledged the devil is in the details of crafting a comprehensive plan and figuring out how to pay for it. He sees one-time American Rescue Plan funds as a potential funding source. “There's work to do to get all of the folks to the table, really put pen to paper and figure out what the needs are,” Jordan said. “I think we're just kind of behind the eight ball in general.”