HOW TO READ THIS STORY: I had a hell of a time writing this. Ask my colleagues. There are extremely important top-line realities that will help voters decide whether to vote to repeal this tax that I absolutely did not want to bury in a super long, super wonky story. But the details matter! And they help explain some of the lingering fears people might have about potentially having to pay this tax later in life, even if they didn’t know it existed until reading this.

So we’re splitting the difference: embedding the most deep-divey content in collapsible sections marked “In the Weeds”. If you want to go super deep, click one of those. If you want to immerse yourself a little, but still keep your head above water, just read the stuff right in front of you. — Luke

One of this election’s most meaningful decisions has been flying somewhat under the radar: Ballot Initiative 2109, a proposal to repeal a statewide tax on specific kinds of capital gains that lawmakers passed in 2021 and which was first collected in 2023.

The tax raised almost a billion dollars in its first year, but a lot of people have no idea it even exists, much less whether they should vote to keep or repeal it.

If you are one of those people, it’s totally understandable.

As taxes go, capital gains are a little obscure. Most of us understand how sales tax affects us because we all pay it, so when there are city and county sales tax hikes on the ballot, we know to pay attention. A capital gains tax, though? Who pays those? And who benefits?

With Washington’s tax specifically, both the costs and the benefits are somewhat niche:

- Only an extremely small percentage of people with high levels of a very specific kind of wealth pay any tax at all.

- The money raised by the tax primarily helps subsidize childcare and early learning programs, meaning it most directly benefits working families with young kids.

If your kids are past preschool, or you don’t make a lot of money from that specific kind of capital gain, you might not even know the tax or the programs it supports exist.

The need these taxes and programs attempt to fill, though, is significant. An estimated 323,000 Washington kids come from families where both parents work. The Washington State Department of Children, Youth & Families (DCYF) estimates only 29% of these kids have access to child-care — subsidized or not — or preschool.

The actual need is probably greater than this.

Those numbers don’t count the families where one parent has to leave the workforce to stay home with the kids because the cost of childcare outweighs the benefits of working — a group that likely includes many poor and working-class people.

This isn’t a problem that only affects urban areas. The DCYF data shows the biggest gaps are in rural areas, where populations are low, people are spread out, and finances are often even tougher. At the moment, rural Garfield County doesn’t have any state-recognized childcare or preschool at all.

The bottom line for the importance of this initiative:

- Very few of us pay the tax

- Many kids and families are benefitting from it

- We all get to vote whether to keep it.

So here’s a rundown of the facts, the fears and the feelings around I-2109, the vote to repeal Washington’s capital gains tax.

In case you’re worried this will be a boring, wonky tax story, here’s a preview of the feelings arrayed on both sides:

Martin Tobias, a Spokane-based venture capitalist, thinks the tax is going to harm investment in the long run. If you tax the people making the majority of the investments, he believes, “You just keep disincentivizing people to stay and invest.”

Tobias told Geekwire earlier this year that he moved from Seattle to feel more free, and told RANGE when lawmakers pass taxes like this — which directly impact his primary means of making money — “they're incentivising me to just keep going.”

Meanwhile, State Senator Patty Kuderer represents the 48th legislative district, spiritual home of Washington's tech sector and home to more big investors than anywhere else in Washington. Unsurprisingly, more than half of the capital gains money collected statewide so far has come from inside her district.

Kuderer is a vocal fan of the tax. Not only did she vote for it, she told RANGE, “I campaigned on it.”

Who does the tax help?

The first $500 million raised by the capital gains tax in any given year funds the Fair Start for Kids account, a pot of money created to support early learning and childcare. The intent is to give kids an early start on learning and make it easier for their parents to stay in the workforce. Anything raised over $500 million in a year helps fund capital projects for public schools — which usually means construction, renovations and certain other big purchases.

Right now the fund provides childcare assistance to families making below 200% of the federal poverty level, or about $43,000 for a family of three or $52,000 for a family of four. In July 2025 — assuming there is still funding — that will expand significantly, to families at 85% of the state median income, roughly $73,000 for families of three or $87,000 for families of four.

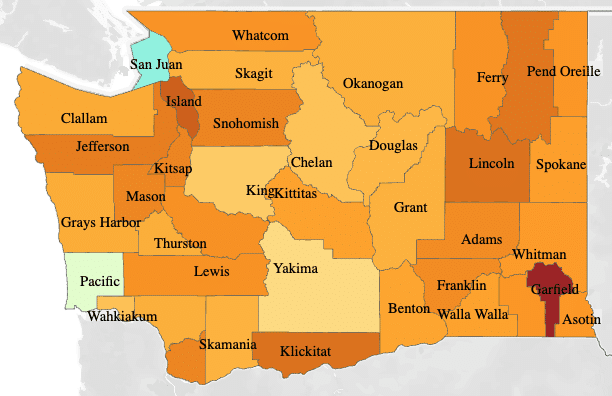

When you map DCYF’s data by county, you see some big pockets of need, like Stevens, Lincoln and especially Garfield county. When you sort by legislative district, though, you start to really see the urban/rural divide.

Spokane is a relatively bright spot surrounded by considerable need for childcare and early learning in rural areas (Source: DCYF)

Throughout the pandemic we have heard stories of the spiraling cost of childcare in Spokane. In this data, though, Spokane is a relative success story, with 38% of toddlers and preschoolers in childcare or early learning in the 3rd Legislative District (an area that encompasses most, but not all of the city). Part of the reason that number is so high is that almost 75% of those 4,200 kids are subsidized by the state.

In the legislative districts surrounding Spokane, including those in Spokane County, the situation is considerably worse, with only about 20% of the toddlers and preschoolers able to access childcare and early learning.

In years like 2023, when collections top $500 million, the additional money goes into a fund for one-time projects. The extra funds from 2023 helped fund approximately 170 school construction and capital projects across the state.

A state lobbyist RANGE talked to on background said these kinds of capital funds can be a real lifeline for schools who have struggled to pass their own local bonds and levies, giving them state money to fix buildings and buy equipment they wouldn’t otherwise be able to pay for.

The data appears to bear this out: only two projects were funded in Spokane County compared with 13 at districts in nearby rural Stevens county, including $3.8 million worth of improvements each in Kettle Falls and Northport. Both Spokane projects supported small, rural districts, too.

In the Weeds | What is Capital? What is a Gain? What is a capital gains tax?

In general, capital assets can be anything from the home you own to your stock portfolio to the small flock of chickens you have in your backyard. In the words of the federal taxman, “almost everything you own and use for personal or investment purposes is a capital asset.”

A capital gain is when you sell one of those assets at a profit. Homes routinely appreciate in value, as do stocks (chickens less so).

A capital gains tax, then, is a tax paid to a government based on the gains you’ve made on the capital you own in a given year, after subtracting your losses.

If you put $1000 in the stock market and it grows to be worth $1 million over time, you wouldn’t pay taxes in Washington on the $999,000 of wealth you had generated until you cashed those stocks in.

For other forms of capital — the kind working people are more likely to have — the Washington law has lots of exclusions, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

For tax purposes, the government lumps capital gains into two broad categories: Short-term and Long-Term. If you’re a house flipper, a day trader or a chicken broker — buying and selling assets regularly — the proceeds of those sales are considered short-term gains. Long-term gains are anything you hold onto for more than a year.

Washington’s capital gains tax is specifically a tax on long-term investments.

In all cases — whether we’re talking about real estate or shares of Microsoft — a capital gains tax usually isn’t paid while your assets are appreciating in value (those are called “unrealized gains”). Capital gains usually only kicks in when you sell the asset and realize the gain.

Your Bitcoin might be going to the Moon, but you won’t have to pay for the capital gains on that trip until you sell the ship that took you there.

Okay, so who pays the tax?

Washington describes its capital gains tax as “a 7% tax on the sale or exchange of long-term capital assets such as stocks, bonds, business interests, or other investments and tangible assets.”

What does any of that mean?

Broadly: in 2023, people who had more than $250,000 of income the previous year from specific kinds of business assets like stocks and other equities — including crypto currency — paid the tax, but only if they held those assets “long-term,” which is generally defined as more than one year. Most forms of wealth owned by working people — like their home and their retirement account — are exempted.

We will dig into the details, but at the highest level: only the absolute wealthiest of the wealthy business people in Washington state have paid this tax so far, and it's very unlikely that will change unless the law is changed.

According to data from the Washington State Department of Revenue (DOR), the tax raised over $896 million in taxes from just 3,354 people in its first year. That’s less than one half of one tenth of one percent of Washington’s 8 million residents.

In 2020, Kiplinger estimated that Washington state had 233,155 millionaires, meaning people and households that “have investable assets of $1 million or more, excluding the value of real estate, employer-sponsored retirement plans and business partnerships.” That number is almost certainly higher today, with Puget Sound Business Journal reporting that Seattle added 3,700 new millionaires last year alone, to bring the city’s total to 54,200. But even if we use the 2020 numbers, fewer than 1.5% of Washington’s liquid millionaires paid the tax.

If you aren’t a millionaire, there’s almost zero chance you have to pay.

As you might imagine from the business journal story linked above, the hyper focus — not just on capital gains, but specifically gains from long-held stocks, equities, crypto and other business investments — creates a strong geographic correlation to who pays.

Agricultural land and livestock are exempted from the tax along with other real estate and retirement funds, and as a result, places with relatively large pockets of agricultural wealth — Washington’s wine country, for example, and the Palouse — don’t show high levels of tax being paid.

Only 84 people in all of Spokane County paid the tax, out of a population of about 550,000. The rural counties surrounding us had even fewer.

One might imagine Martin Tobias — the Spokane venture capitalist we mentioned earlier — is one of those 84 people, but he isn’t.

“I was subject to the tax,” he says, meaning he had to submit a tax return to the state, “but I don't believe I've paid it.”

Tobias says he has roughly 250 active startup investments currently in his portfolio, and is able to exit a handful of those investments every year. He doesn’t control the timetable on those investments, though, and the failure rate in early stage venture capital is about 90%, so all VCs lose a lot more than they win.

Because of all of that, Tobias says he had “carry forward losses” in 2023 that he was able to deduct from any gains he had, leaving his profits lower than the $250,000 exemption.

That isn’t enough to make him happy with the law, though, he says. Tobias hasn't gotten where he's gotten by achieving small gains with the occasional loss to achieve modest profit. That's not how venture capital works. His business exists to take big bets on the chance that 1 in 10 will lead to a huge capital gain. It’s only a matter of time, he says, “At some point I will pay it.”

To this point, though, the overwhelming majority of tax collected has come from Washington’s tech heartland, not just King County or even the Seattle area, but a specific cloister of suburban cities (Redmond, Kirkland) that have powered the region’s tech boom, and their wealthy enclaves (Medina, Hunts Point, Yarrow Point).

Put simply: the biggest tax payers in Washington state are, most likely, Patty Kuderer’s constituents.

In the Weeds | How the tax breaks down by wealth

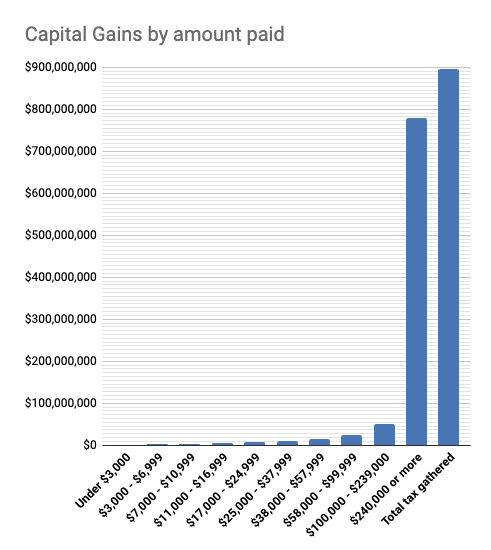

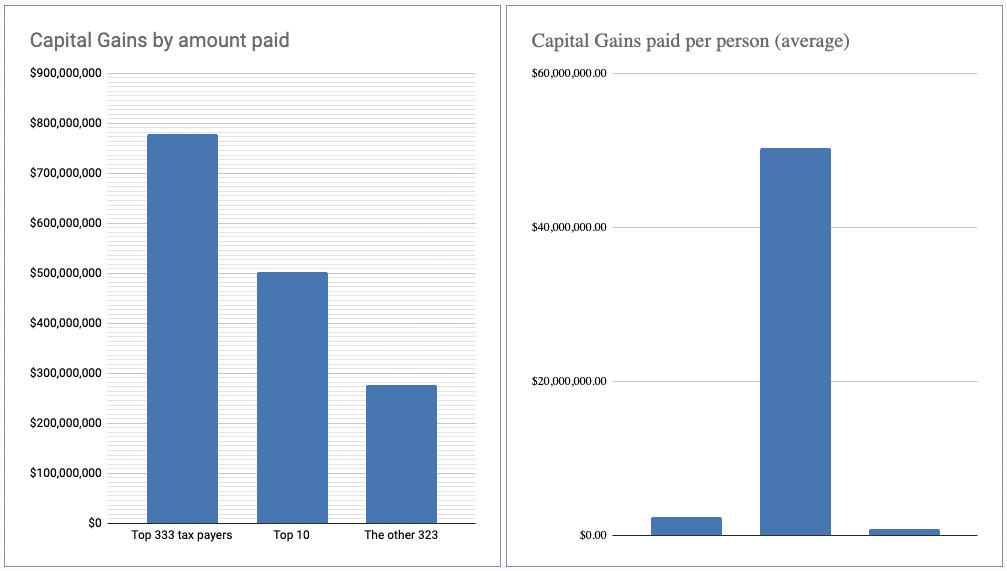

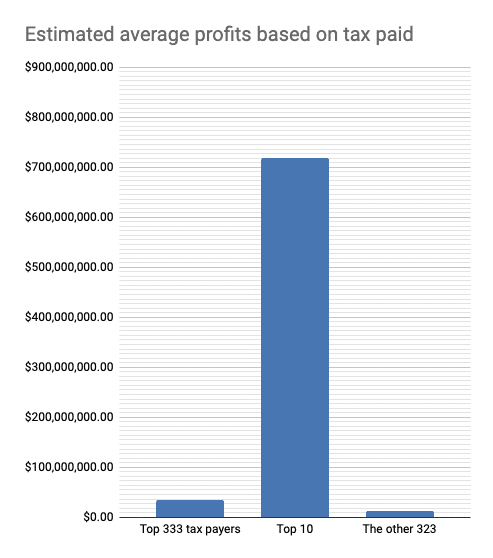

The top 10% of those 3,354 capital gains tax payers account for almost 87% of the tax paid. That means the 333 people with the biggest stock paydays in 2023 paid $778 million alone.

Here’s how that looks in a graph:

So the vast majority of taxes were collected on the top 333 tax payers, but even that number is a little deceptive. If we pull out just the top 10 individual taxpayers we see they paid over $500 million by themselves, or about $50 million per person.

This is anonymous data, so we don’t know for sure who these folks are, but when you get to the top 10 we can assume it’s people with the absolute most stock wealth in Washington — people like Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer, for example, and potentially some venture capitalists and hedge fund managers who aren’t household names. These 10 people paid just under 65% of the tax paid by the top tier.

Compared to these whales, the other 323 paid the remaining $275 million, or about $850,000 per person.

These charts show just how much more, on average, the top 10 wealthiest people paid compared to their next 323 richest peers:

Because this is anonymous data, we can’t see individual tax returns, but there’s one more general view I wanted to point out. If the top 10 capital gains payers Washington paid about $50 million apiece, that means they must have had average stock earnings in 2023 of about $718 million dollars each, compared with an average of $12.5 million for the other 323 top tax payers.

The data we have doesn’t get more granular than that, so we don’t know if one or two truly huge players are driving the average of the top 10 up, but Washington has an estimated 11 to 13 billionaires, so it seems likely they, along with Washington’s estimated 130 centimillionaires (those with $100 million of relatively liquid, investable assets), represent the bulk of these tax payments.

People who buy and sell this much stock almost certainly have other assets like houses (and, in the case of Bill Gates, more farmland than some countries). They might even be a CEO of a company and take a salary.

Washington’s capital gains doesn’t even consider any of these income and wealth sources, so our beautiful billionaires and centimillionaires are in no danger of losing their status because of this tax.

In the Weeds | How the tax breaks down by geography

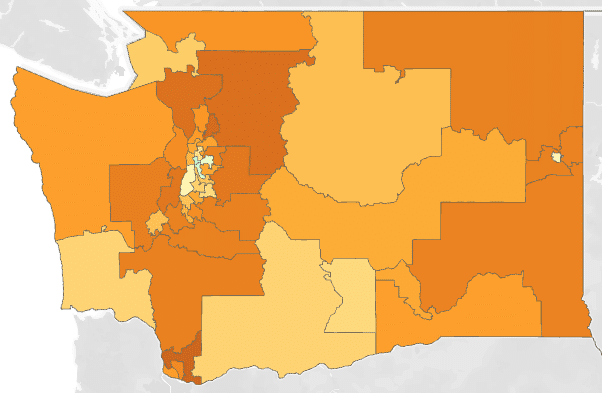

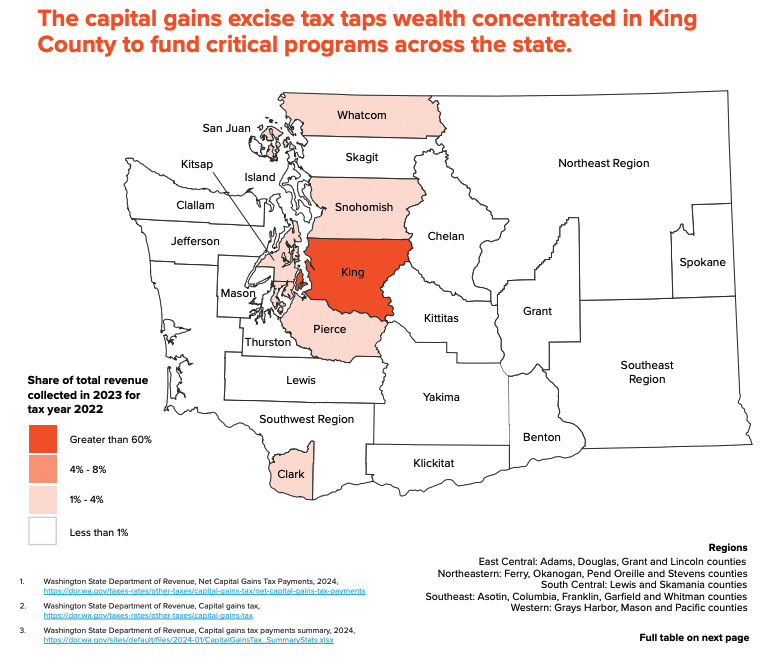

According to data from the Department of Revenue, over 83% of the tax money raised in 2023 came from King County. The Washington State Budget & Policy Center, a non-partisan research and policy organization, turned that data into a map, which has a number of interesting things to note:

Not pictured: the 124 individuals who paid more tax than almost every county in Washington, despite not living in Washington.

First, Seattle and its wealthy suburbs and exurbs in King, Pierce, Snohomish and Kitsap county paid about 89% of the tax, but only Snohomish county (3.32%) paid more than 3% of the tax. The state’s 3rd biggest contributing county was Clark (2.86%), home to Vancouver and other cross-border suburbs of Portland, Oregon.

Every other county in Washington — very much including Spokane, the state's 4th-largest by population — paid less money into the tax fund than the 124 individuals who paid $23,617,280, despite not actually living in Washington.

Many of the state’s more rural counties, including every county surrounding Spokane, had totals so small researchers grouped them geographically into regions.

In all, only six counties paid more than 1% of the total. Spokane paid approximately $7.9 million, or about nine tenths of 1 percent.

If we zoom in on King County, we see that big orange splotch is a little misleading. It’s true that 2,187 King County residents paid a total of just under $750 million in capital gains tax, but that isn’t spread out evenly.

The DOR also broke the numbers down by legislative district, showing that $490 million — almost 2/3rds of the money collected in King County and about 55% of the state total — came from a single area: the wealthy cities and enclaves just east of Seattle in Washington’s 48th Legislative District.

The filet of a very prosperous region.

Only two other legislative districts paid more than 10% of the amount paid in the 48th. The 41st district, immediately south of the 48th, including the exclusive Mercer Island, paid almost $59 million. The 43rd district — which includes Seattle’s Belltown, Capital Hill, Eastlake and Madison Park, the lakefront community that looks directly across Lake Washington at Medina — paid about $64 million.

A fourth group — 499 people who, presumably, had several houses within the state but no home address on record — paid just over $50 million.

Only one other district paid more than $25 million and only four districts paid more than 10.

The other 41 districts in the state paid less than $10 million. Most of them paid far less.

In Spokane’s 3rd legislative district, which includes most but not all of the city, 23 souls paid just over $2.6 million, or about $113,000 apiece. That’s good enough for a little less than ⅓ of 1 percent of the tax taken.

None of this is to say there aren’t people with tremendous wealth in Spokane or the county.

It’s just likely their wealth is tied up in real estate or some other non-liquid asset. It’s also possible that those who do have significant wealth stored in investments and business ventures, but didn’t realize many gains in 2023, so they weren’t subject to this particular tax.

In the Weeds | How do you design a tax that targets so few people?

You start with a kind of asset most working people don’t regularly buy and sell: ownership in companies.

Ostensibly, the capital gains tax is a 7% tax on profits above $250,000, so if you made $250,001, you would pay 7 cents in tax.

But taxpayers are also allowed to deduct large charitable donations, as well as losses from similar kinds of long-term investments that lost money — a stock sold at a loss, for example, or an investment in a startup that failed.

It’s uncommon in Washington for a person to have more than $250,000 in profit from stocks and business investments every year, but it’s increasingly common for people who have owned a home for a while to make that much money when they sell — even in less wealthy places like Spokane.

So when writing the capital gains bill, lawmakers explicitly carved out big exceptions in order to not accidentally tax working people for things like one-time windfalls, like the sale of a house, or for investments designed to help them through old age, like retirement accounts.

The intention, according to outgoing Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig, was to tax only the wealthiest people in Washington and use that money to “ease the burden” on working people.

The bill’s passage in 2021 was the result of work that began years before the pandemic, talking with people across the state of all income levels about how to better fund the kinds of education services that poor and working families needed without taxing those same families. The law specifically excludes entire categories of capital:

- The sale and exchange of real estate — even second homes and income properties

- 401Ks, IRAs and other forms of retirement accounts,

- Horses, livestock and agricultural land

(For a deeper dive on the many exclusions and deductions, here’s a good rundown in layman’s terms.)

Billig said lawmakers early on tried to figure out how to tax the sale of second and third homes, but they couldn’t find a way to do it and ensure they didn’t accidentally tax working people who happened to have a lake cabin that had been in the family for generations.

If you’re a business owner who sells part or all of a business that qualifies as a federal Qualified Small Business Stock — allowing you to exclude some or all of those profits from federal capital gains taxes — then Washington state lets you exclude them from state taxation as well.

At the end, that left lawmakers with a relatively small set of assets they felt comfortable taxing: “It’s really just stocks, bonds and business [investments],” Billig said, “ — and we even have exclusions for certain business sales.”

If you’re anything other than a specific kind of long-term investor operating at a very high level, you will never have to pay this tax.

You probably don’t even personally know anyone who has paid this tax. Especially if you live in places like Spokane or Battleground, Tacoma or Tekoa — basically anywhere outside of Washington’s tight knit tech and investment bubble.

A Battle of Millionaires and Billionaires

For a state of about 8 million people, Washington is over-represented on the list of the world’s wealthiest people.

While we have a relatively modest 11 to 13 of the United States’ estimated 756 billionaires, we are the home or former home of a few of the absolute biggest fish.

According to Forbes’ Real-Time Billionaires list, there are currently 16 people in the world who have more than 100 billion dollars. Two of them — Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer — live a couple miles from each other in Medina and Hunts point, respectively, wealthy enclaves between Seattle and Redmond.

A third, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, used to live nearby as well, before very publicly moving to Florida around the time the capital gains tax took effect. He still owns what Architecture Digest calls his “longtime Seattle compound” in Medina.

All of these areas are in the 48th legislative district, represented by Senator Kuderer. If these ultra-wealthy people are upset about the capital gains tax she worked to pass, though, she’s not aware of it.

“[Gates has] never called me, he's never reached out to me for anything,” Kuderer told RANGE. “Ballmer lives in my district. He's never called me, either. His wife has, but she's called me to help work on gun safety laws.”

Kuderer says she’s never heard from Jeff Bezos, either, not when he lived in her district and not since he left. Officially, Bezos said the move to Florida was to be closer to family and his vanity space company, Blue Origin, not tax reasons, but that didn’t stop the financial press from guesstimating he would save about $600 million in taxes on expected stock sales he would be paying between now and 2025 if he still lived on Lake Washington.

Gates, meanwhile, recently published a vanity Netflix documentary series, with one of the episodes advocating higher taxes on people like him. This specific tax, though: Kuderer says it's been crickets.

That doesn’t mean, however, there aren’t wealthy people in the fight to repeal. They’re lined up on both sides:

The initiative to repeal the capital gains tax was sponsored by Brian Haywood, a wealthy hedge fund executive, big Republican donor, and self-proclaimed “economic refugee” who moved to King County from California.

On the other side, one of the primary funders of the No on I-209 campaign is also very wealthy: Nick Hanauer. Like Martin Tobias, Hanauer has done early stage venture capital investing, and was the first person outside Jeff Bezos’ family to invest in Amazon. Hanauer is perhaps best known for championing the fight for a $15 minimum wage in Seattle. While early news coverage dubbed him an “activist billionaire,” more recent reports have Hanauer merely calling himself “obscenely wealthy.”

In Spokane, Tobias is adamantly opposed to the tax and hopes it is repealed. Though he isn’t actively part of Heywood’s initiative effort, he said he has taken part in previous attempts to block the tax. When former Washington Attorney General Rob McKenna brought a lawsuit in 2021 in Douglas County Superior Court seeking to have the tax declared unconstitutional, Tobias says, “I was part of that lawsuit.” The plaintiffs won the initial suit, but that decision was overturned by the state Supreme Court in 2023.

Tobias has a history of opposing taxes. He was also a plaintiff in a 2017 lawsuit also brought by McKenna seeking to have a proposed City of Seattle income tax declared unconstitutional. (Among the co-plaintiffs in that case was Christopher Rufo, who achieved national notoriety as the primary force behind conservative campaigns against critical race theory.)

Last month, Tobias told RANGE the move from Seattle to Spokane might be short lived. The capital gains tax makes him want to just keep moving. “I’d go to Wyoming,” he said, “Wyoming has the best [tax structure]” for investors like him. "Or I might go to Nevada.”

Talking with Tobias, it’s clear he loves the thrill of the hunt as an investor, but he also thinks he’s making the United States stronger by being the first or nearly the first person to take extremely risky bets on the country’s smartest young tech founders.

He thinks that many people like him are in a similar situation, driven by a desire to take their wealth and invest in something that might become the next Google.

By taxing people like him, the state is just begging wealthy investors to pack up as well, like Jeff Bezos did when he moved to Florida.

For Tobias, it's a matter of principle. He says if he had to pay the tax, “it's not going to change my life that much.”

“That seven percent that would go to the government is not money I would have spent on my family or house or anything like that,” he says. It’s money he would have invested in more companies.

“And the question is: is the government gonna make a better use of that than I would?” he asks, ”Pretty much — obviously — no.”

For her part, Senator Kuderer doesn’t know if the majority of her wealthy constituents lean more toward Tobias or Gates, but she has won her state senate races comfortably here.

One thing she's sure of: if her neighbors are mad, they aren’t telling her. “In fact, I was knocking on houses in Yarrow Point, and a man who clearly was going to be paying the capital gains tax told me to go for it, because it wasn't going to make a dent in his lifestyle.”

Kuderer also says it remains to be seen if more wealthy investors leave Washington, but there isn’t evidence of it happening very often, yet. Bezos may have left, but his ex-wife MacKenzie Scott, who has become a philanthropist known for audaciously large gifts, still lives in Seattle. Plus, if they do, but still invest in Washington-based startups, they'll still be subject to the tax on those gains — a stream of revenue from out of state that has already collected just under $24 million.

Kuderer also thinks that, even if individual super wealthy people do move, Washington’s tech ecosystem will remain. People who start the kinds of companies Martin Tobias invests in need more than just beneficial tax structures. They need access to large pools of highly educated talent. Those talented employees — in order to stay in the job market — need to be able to afford daycare for their kids.

Whatever else you can say about the capital gains tax, Kuderer believes, it’s focused on helping pay for the kinds of services that made Washington attractive to tech in the first place.

“The initiative [to repeal the tax] will benefit the person who paid for the initiative, Brian Haywood. People like him, in his income category,” Kuderer said. “It's going to harm their employees and their kids, it's going to cut back on the ability to get daycare, and like I said, it's going to cut back on our ability to fix broken schools.”

For that reason, Kuderer thinks repealing the tax might have a bigger impact on Washington’s tech ecosystem than maintaining it.

After all, Jeff Bezos may have moved to Florida, but Amazon’s primary headquarters is still in Washington.