When she lost her job at sixteen years old, Hallie Burchinal found herself homeless in Spokane in the 1980s. She put in applications for every type of entry-level position she thought a teenager like herself would be qualified for — mostly frozen yogurt shops, she told the Spokane City Council at the meeting on July 22.

But any time she disclosed her housing status during job interviews for those positions, “I wouldn’t make it any further in the process,” she said.

Now, about four decades later, Burchinal serves as the executive director of Compassionate Addiction Treatment Spokane (CAT), an organization providing homelessness services, led by people with lived experience. Still, she says, not much has changed when it comes to the stigma unhoused people face when they look for jobs.

The stigma is so pervasive that several employees currently working at CAT didn’t feel comfortable revealing they were unhoused during CAT’s application process — even at an organization that centers lived experience.

“They didn’t disclose that out of fear of not being employed,” Burchinal said, which really struck her. “Once they trusted enough that they felt they could reveal that, then we were able to move underneath them and help them through that process. One of those people has been with us for almost four years and is an absolutely incredible part of our team.”

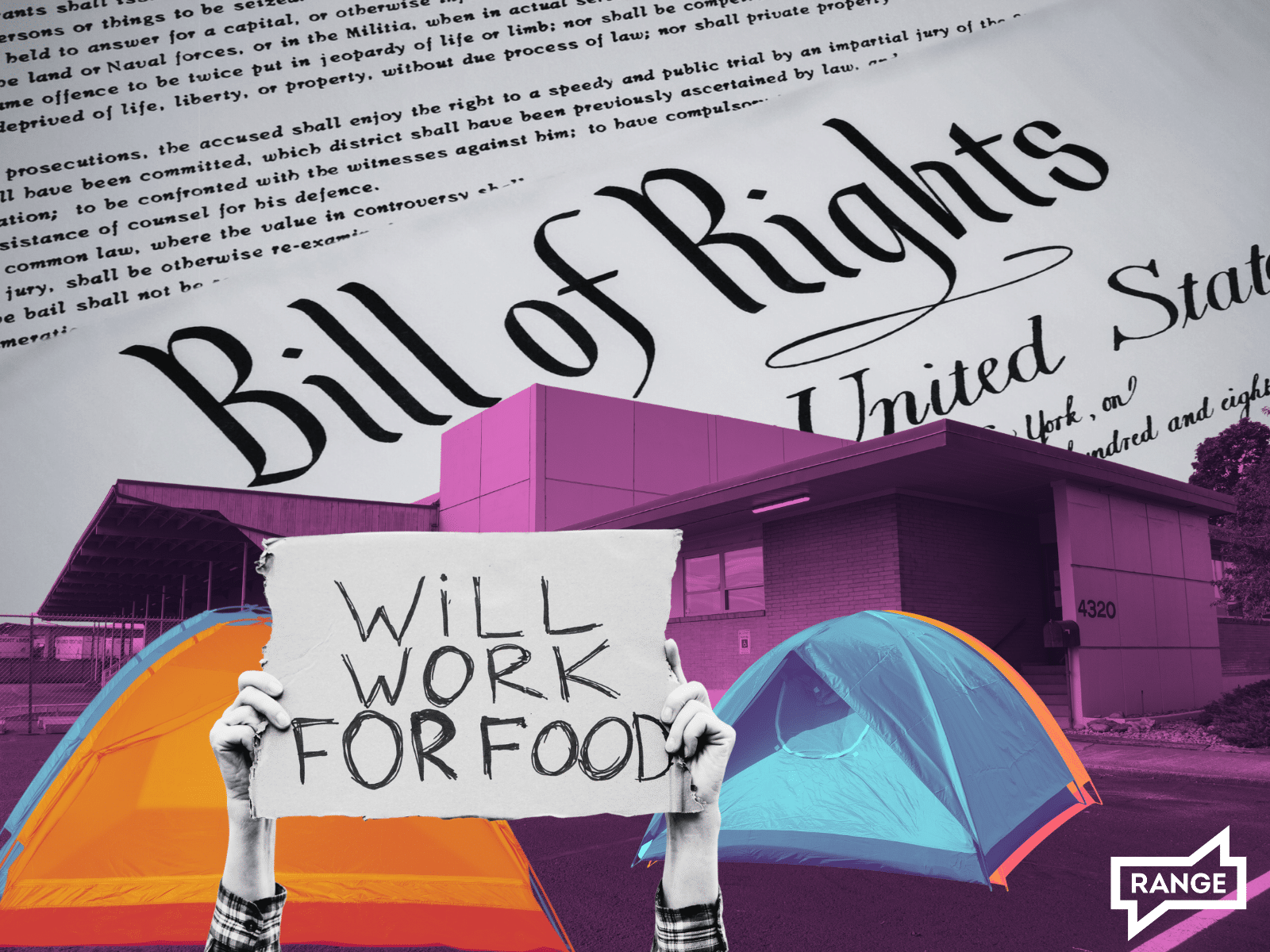

Burchinal shared this story as part of her testimony in support of a new ordinance that would codify housing status as a protected class and enshrine “the human rights and basic dignities of individuals experiencing homelessness.” Since the first reading of the ordinance on July 22, the legislation has drawn criticism, confusion and requests for clarification — mainly from business owners and representatives of organizations like Downtown Spokane Partnership (DSP) and the East Spokane Business Association (ESBA).

The ordinance, which is the first piece of legislation Council Member Lili Navarrete started working on when she took office in January, is co-sponsored by Council Member Kitty Klitzke and based off of a resolution passed in October 2023 by the Spokane Human Rights Commission.

It is scheduled to go up for a vote on Monday, August 12 (although Navarrete says it’s possible it get deferred for one week for a final legal review on a proposed amendment) and we figured we’d break the ordinance down to debunk the fictions, give you the facts and address the fears before this comes back up for public discussion and a potential vote.

What the ordinance does: the facts

Though some criticisms of the proposed ordinance — like those in an email sent to City Council Member Paul Dillon by Barbara Woodbridge, president of ESBA — claim it will make homeless people in Spokane “‘untouchable’ by the law,” it’s actually pretty limited in scope.

Primarily, the ordinance would add “housing status” to the list of protected classes protected from discrimination, and defines “individuals experiencing homelessness” as anyone who doesn’t have a fixed or regular residence. The list of protected classes currently enshrined in the city’s municipal code includes race, religion, creed, color, sex, national origin, marital status, familial status, domestic violence victim status, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, honorably discharged veteran or military status, refugee status and the presence of any sensory, mental or physical disability.

By adding housing status, the city would be signaling to itself, landlords and other business owners that unhoused people can’t be refused services or funding solely because they’re unhoused, and ensuring that job candidates cannot be rejected by potential employers solely because they disclose homelessness, lack a permanent mailing address or list a shelter as their address.

It would also codify a few other rights for unhoused people like:

- The right to retain their own personal papers and other essential property when “receiving comprehensive support services,” like entering a shelter, addiction recovery services or transitional housing. (This does not apply to sweeps or abandoned property, which are covered below.)

- The right not to be excessively searched when seeking or receiving those support services. Navarrete said she understood shelters’ need to search people upon entrance to ensure no one is bringing in guns or drugs, but “once they’re inside, there’s no reason to target anybody or seize a property that’s not illegal to have or goes against “policy.” Navarrete’s legislative aide Andres Grageda reached out to 15 shelters in the city as research for the ordinance and found that 99% of Spokane’s shelters say they are already abiding by this standard, but they are also in favor of the ordinance codifying it as right.

- The right not to be excluded from private property that is typically open to the public, like malls or stores, solely because of their housing status. While business or property owners technically don’t need a reason to ask someone to leave their property, it is unlawful to trespass someone solely because they belong to a protected class. For example, you can’t ask someone to leave your restaurant just because of their race or gender, or because you think they look gay, but you can ask them to leave if they yell at a server, even if they happen to be a member of a protected class. This would ensure the same level of protection for unhoused people: you couldn’t tell someone to leave simply because you assumed or knew their housing status, but you could if they were exhibiting disturbing behavior.

- And, potentially the most controversial and misunderstood section of this ordinance, the right to move freely in public spaces. Current laws on the books limit camping in certain areas (like Prop 1), being in the city’s parks after dark or sitting and lying down on public sidewalks. Though these laws are under challenge from an ACLU lawsuit that alleges these violate the state constitution’s regulations forbidding cruel and unusual punishment, this ordinance would not limit their enforcement. Someone who is homeless could still be arrested or cited for violating the aforementioned laws, but they could not be cited just for, say, walking down the street while homeless, or being in the park during daytime hours while homeless.

If this ordinance passes and an unhoused person feels they have been discriminated against in a way that violates the protections spelled out in the ordinance, they can submit a complaint to the city. The process already exists but will be clarified during Monday’s Urban Experience Committee meeting, but ultimately complaints will be reviewed and investigated by the city’s Hearing Examiner. If the complaint is found to have merit, the city will first try to resolve it via a mediation process, and if that fails, it will be submitted to the City Prosecutor who will determine if a civil infraction can be filed.

What it doesn’t do: the fictions

Despite the relatively limited scope of the ordinance’s powers, a lot of fiction has been floating around. Steve Corker, a former Spokane City Council member, testified on July 22 that he’d gotten a lot of calls from people confused about the ordinance, thinking that it’s “going to be a license that protects bad behavior.”

Emilie Cameron, president of DSP, said in an email to council members that the organization had received a number of questions from downtown business owners about the proposed legislation, like “How could this effect enforcement of prohibitions of public drug use, if that person is homeless?” and “How will this affect the ability of law enforcement to enforce city ordinances that maintain clean, clear and safe public spaces like unlawful camping or sit-lie?”

Navarrete and Grageda sent detailed answers to all of the questions in Cameron’s email, but we figured it would be simpler and more accessible for everyone if we shared them with everyone.

Fortunately for everyone who may concerned about the ordinance, the list of what it does not do is a lot longer than the list of what it does do:

- It does not does not make unhoused people “‘untouchable' by the law,” as Woodbridge claimed in her email, or remove consequences for committing crimes. Business owners seemed to be concerned they would no longer be able to call the cops on people for things like trespassing, destruction of property or theft because it might be considered discriminatory under the ordinance if the person committing crime was unhoused. They don’t need to worry.

Here’s a handy guide: If someone from a protected class commits a crime, you can call the cops. If you see someone from a protected class simply existing, and it bothers you, you cannot call the cops. Breaking a law is breaking a law, but existing while homeless is *not* illegal, even if some people in Spokane seem to wish it was.

- It does not prevent the enforcement of Prop 1, sit-and-lie laws or the No Parks After Dark ordinance. Again, if you’re doing something illegal, you can be held accountable for it, regardless of whether or not you’re considered in a protected class.

- It does not prevent sweeps or the clean-up of abandoned property. Cameron’s email stated there were some questions around “perceived liability” for business owners if they were to dispose of any belongings left on their property that might belong to unhoused people. According to Navarrete, the property protections only extend to essential property — things like driver’s licenses, medical records and medication and birth certificates, and are only a factor when an unhoused person is entering into comprehensive support services. It wouldn’t apply to property left in a business or outside. Her proposed amendment would also further clarify and define comprehensive support services. So it would technically still be legal to throw away a driver’s license or medical records left inside your business. (Whether or not throwing away someone’s core ID is a total asshole move is outside the scope of city jurisdiction and therefore outside the scope of this article.)

- It will not force businesses out of Spokane. Woodbridge claimed that this ordinance would make local businesses leave because they’ll perceive it as “an impossible endeavor to participate in commerce in this city.” Nothing in the ordinance says that businesses have to leave Spokane, just that they can’t make someone leave their property solely for being or looking homeless. If it is impossible for you to conduct profitable business without discriminating against unhoused people, maybe there’s a bigger underlying problem with your business.

- It does not “reward individuals for remaining in a state of homelessness,” like city council frequent flier Will Hulings claimed in his testimony on the first reading of the ordinance. Unhoused people receive no compensation or rewards, monetary or otherwise as a result of the ordinance.

- It does not cost any money. Cameron inquired about the fiscal impact of the ordinance on the city’s budget. For those budget hawks, we have great news: It costs $0! The only potential impact or use of city resources would be staff time from the Hearing Examiner’s office to review any complaints of discrimination submitted by people experiencing homelessness. That office already reviews complaints of discrimination by other protected classes in the city, so it would just add one more group of people to the list that could submit complaints.

- It does not solve homelessness. However, it may make it easier for them to get off the streets by ensuring their essential documents are protected while they utilize services, and guarantee that they are not turned away from potential employment opportunities because of their housing status.

“I also understand the business concern,” Navarrete said. “I was a business owner and our businesses were vandalized quite a bit. I also live two blocks from Camp Hope.”

In fact, she believes the ordinance will make it easier for unhoused people to get off the streets. “If we want our houseless folks to [thrive], we need to give them the protection of not being discriminated [against],” she said. “We want them to get jobs so they can make money and look for housing.”

What people feel it will do: the fears

While the public testimony for the first reading of the ordinance was overwhelmingly positive, especially from multiple community members who had experienced homelessness themselves, there were a lot of fears, both concrete and intangible, revealed in emails sent to city council members.

ESBA, which Woodbridge leads, was officially established in 2003 to support the East Spokane Business District. Conservative donor Larry Stone (and owner of the warehouse the Trent Shelter is in) also holds a leadership position in the organization, which touts itself as a “citywide leader in stopping camping on public property and enforcing sit-and-lie laws,” and has funded it in the past with charitable contributions from The Stone Group. ESBA was one of the loudest voices advocating for the closure of Camp Hope, though, at the time, one of their talking points was that unhoused people would receive more “humane and compassionate care,” at shelter facilities.

According to Woodbridge, that compassion has run out. “We believe that the contempt towards the people living on our streets has come from a complete lack of accountability for the lawlessness that follows many of those individuals,” Woodbridge wrote in her letter, acting in her role as a leader of ESBA. “We have witnessed our homeless population openly use drugs, destroy property, and instigate many instances of violent crime. While we know that it is not all the people living on the streets who take part in this, we believe it has become the majority. Many citizens who once had compassion for these people, no longer do.”

Woodbridge didn’t offer any concrete evidence for either the assertion that the majority of unhoused people use drugs and destroy property or the assertion that “compassion for these people” has dropped over time.

Woodbridge also stated that she feared the ordinance would lead to more destruction of private property because “the ones who had little fear of consequences will believe they now have none.” She also feared that it would create “an even larger decrease in the compassion for the homeless,” because it would set them above the law.

Woodbridge concluded her letter by painting a truly apocalyptic picture of what she and ESBA believe Spokane will look like if the ordinance passes: “As people from all areas of the nation hear that they will find refuge and no accountability for degenerate behavior, the worst of the people in this population will descend upon our city.”

Others, like Ami Manning, the Executive Director of Experience Matters, envision a much brighter future created by the ordinance — one where the city finally lives up to its motto: “In Spokane, We All Belong.”

“This is a moment where Spokane gets to be better,” Manning said. “Criminalizing homelessness is not something that actually reduces our homeless population.”

Burchinal said the ordinance is “humanizing” and “brings us all back to having the same rights and protections as all other people within our community.”

“It begins the long process of eliminating the experience of homelessness as a shameful experience that defines who we are and defines our rights to access to employment, public spaces that we all enjoy,” Burchinal said as she implored her fellow citizens to speak out in support of the legislation. “It’s really important, it could have changed my life back when I was walking through [homelessness] myself.”

For Navarrete, the legislation is simpler and less threatening than people think.

“When the words houseless and the word rights are together, everybody just goes nuts. Everybody’s like ‘oh my god, you’re going to give them the rights to sit there and blah blah.’ We just want to give them the right to not be discriminated [against] when they want a job.”