This story was published in partnership with the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights, who provided data analysis.

Flock cameras are used to solve serious crimes. Or at least, that’s how local and nationwide law enforcement market their usage of the integrated automated license plate reader (ALPR) networks to the general public.

In a marketing post hosted on the Flock website, the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office (SCSO) highlighted the results of the camera usage. It claimed “a staggering 16 stolen vehicles were recovered within a month, all thanks to technology-enabled policing,” and “20 arrests, a direct outcome of technology, bolstered the crime-fighting prowess of the force.”

County spokesperson Mark Gregory recently told KXLY that in the last two years, they’ve found 17 missing people, arrested 572 suspects and recovered 247 vehicles. For the sake of simplicity, if you assume all of the 572 suspects were found guilty, that’s at most 836 crimes solved using Flock cameras in the last two years. We don’t have data on how many Flock searches SCSO has made from 2023 to 2025, we only know how many searches they made in the first six months of this year: 101,358.

That means that even if every single one of those 836 cases were solved in the first half of 2025, the efficacy of the cameras would be just 0.82%. So in the absolute most generous reading of the data, the Sheriff’s department is solving about eight crimes for every 1,000 searches. If we average Gregory’s crime data across the two years of reporting, for the six-month period we have Flock search data, the number is closer to just two crimes solved for every 1,000 searches.

But in the 2,301,239 searches made on the Spokane County Flock cameras from January 1 to June 23, we found numerous examples of strange, suspicious and sometimes darkly comedic searches made by both local and nationwide law enforcement. Here are some examples of what we found.

First, the funny

Spell your Flock searches correctly, challenge level: impossible.

One thing that made analyzing the overwhelming amount of data in the network audit difficult was the sheer number of misspellings that made grouping and counting searches tricky.

Want to know how many drug-related searches were made on the cameras? You also have to search “drigs” and “drygs.” Other misspellings that tripped up our data analysis include:

- “Stolen vicle,” searched by an SCSO deputy.

- “miscellaneius” — a questionable search even before the misspelling — searched by an officer from New Castle County, Delaware

- “cajacking,” searched by an officer in Des Moines, Washington

- “Suspcious Vehicle” searched by a Spokane Police Department officer (who did include a corresponding case number.)

Internal acronyms used by individual departments also created interesting searches, like “omg” “Eagle Ridge burgs,” and “sus” — presumably meaning “outlaw motorcycle gang,” “Eagle Ridge burglaries” and “suspicious,” respectively. But often, these acronyms aren’t accompanied with case numbers or clarification, making it tricky if not impossible to determine their legitimacy.

Is “TBD” a search where an officer couldn’t make up their mind, or a search for a vehicle related to “theft by deception?” Is “Narc” a search for a narcotics related crime, or for a whistleblower?

With no case number, we don’t know, and agencies auditing their own searches might not either.

What is Flock and who else has access to these cameras?

Flock is a surveillance technology brand that sells a specific brand of Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) that are used on a subscription basis by law enforcement agencies across the state.

The cameras constantly log photos of any car that drives past them, whether that driver has potentially committed a crime or not, which is then stored for up to 30 days in a database owned by the law enforcement agencies. That database can then be searched by whoever has a direct log-in to it, or any agencies that it has been shared with. Read more about Flock cameras in our region and where they’re located here.

The Spokane Sheriff’s network currently has more than 60 Flock cameras operational within the county, including mobile Flock cameras mounted on vehicles that move around the area.

Other ridiculous-sounding searches we noticed on the Spokane County network audit include:

- “Operation Pimp Juice,” and “pimp+juice,” searched by officers in Tennessee, who gave no corresponding case numbers. These could be related to a joint human trafficking operation between Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Tennessee law enforcement, as an archived press release from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and news coverage from the region come up when you Google search for Operation Pimp Juice.

- “Serial Beer Thief,” searched by officers in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which seems to be a more frequent problem than you’d think in Tulsa.

- “Stolen excavator,” searched by an SCSO analyst. We found this news story about a man who stole an excavator and ran over his neighbor’s lawn, not to be confused with the more recent story about another excavator theft, resulting in the destruction of a newly built home. Interestingly, neither of these incidents happened around the time of the search. Perhaps a mysterious third, underreported excavator theft happened?

- “City d ass 2,” searched by an SCSO deputy. We still have no idea what this was about.

- “‘Jared’ is suspected of transporting illegal drugs from IL to NE’” searched by a police department in Nebraska. A quick google search didn’t reveal any additional details as to who “Jared” is or what “Jared” might be an alias for.

More legitimate, but still humorous, queries include “Black market marijuana” by Michigan State Police, “illegal+fish+possession+” by a Wisconsin sheriff’s office, “stolen golf cart,” by a county in Georgia and “METH,” searched by the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics.

Without additional information or case numbers, it’s hard to tell exactly what an officer searching “METH” is trying to use Flock cameras for.

The suspicious

Other searches on the Flock network caught our eye for less humorous reasons. One of the key issues privacy and accountability advocates have railed against is the lack of accountability in network audits across the country. For example, if an officer just searches for “.” or “1” or “wanted person,” it’s impossible to know what they are actually looking for and why.

Some search fields seem to hint at more nefarious use.

Fifteen searches were made on the Spokane County network for variations of the phrase “bad guy.” “Wanted bad guy,” “bad guy,” and “bad guy locating,” all appeared on the network audit. Only one of those searches — “bad guy locating,” made by a Spokane Police Department officer — was accompanied by a case number. Eleven of those searches, made by an officer in Mississippi, read “NA” in the case number field, likely meaning Not Applicable.”

One search from a Wisconsin deputy gave the sole reason as “civil,” which seems to represent the opposite of using the cameras to solve crimes.

Many searches are incredibly vague, like “intel,” “welfare,” “undefined,” “wanted,” “criminal,” “ongoing investigation,” “xxxx,” “law,” “visits,” or “dice,” — no case number attached. Again, these searches could be legitimate, or they could be for undocumented immigrants or victims of police violence.

There were also searches made by local officers that violated department policy.

The public transparency portal for SCSO says traffic enforcement is a prohibited use of Spokane County cameras. Yet, two SCSO deputies explicitly searched for vehicles with traffic violations. Two searches were made for “traffic infraction” and two for “TRAFFIC.” Additionally, one Spokane Police Department (SPD) officer made a search for “Traffic offense.”

SCSO employees also made multiple searches on behalf of agencies in Idaho. Five searches were made on request of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) in Idaho. Six searches were made for cases in Kootenai County — where Sheriff Bob Norris has said his office is actively working with the federal government to support the Trump administration’s goal of deporting as many people as possible.

One of those Kootenai County searches had no case number attached.

Another suspicious pattern we noticed was discrepancies in how long data is stored. The SCSO public-facing transparency portal says they only store data, like photos, for 30 days (though they preserve their search log for longer for audit and accountability purposes.) However, we noticed dozens of searches where the date the searcher was seeking Flock photos and information from was more than 30 days prior to the date they actually submitted the search. In some cases, the time lapse was eight months.

We asked SCSO spokesperson Mark Gregory whether searching for “traffic,” would be an allowable use of the cameras, and how deputies could be searching Flock for data stretching back months if records are only maintained for 30 days, but he didn’t answer. We will update this story if he ever does.

The sad

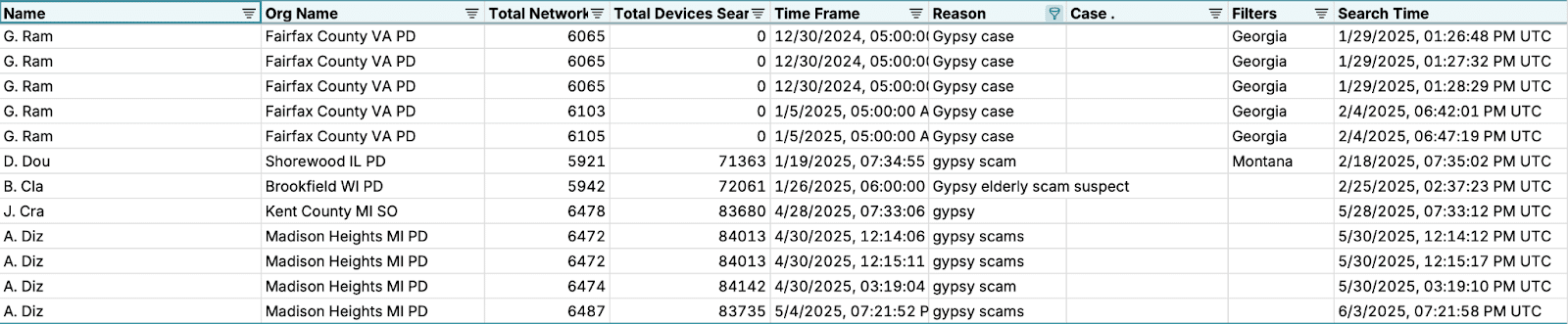

In November, the Electronic Frontier Foundation reported that more than 80 law enforcement agencies made searches that included harmful, stereotyping language against Romani people, which perpetuates racial stereotypes and systemic harm.

Twelve of those searches appeared on Spokane County’s Flock log too. One of those searches, from a deputy in Michigan, was solely the word “g*psy.”

The network audit showing searches made using a slur for the Romani people.

To us, one of the most striking uses of Spokane County’s Flock cameras was a search made by a Florida police officer for a crime at a Publix. The search reason just read:

“Baby formula theft.”