Buckle up, folks. This is a long one. If you want to pop earbuds in and listen instead (maybe while you take a walk downtown?), we’ve got you. Note: the audio version of the story does not reflect edits made post publication – a quote from County Commissioner Josh Kerns stating that he did not have a competition with County Commissioner Al French to get a meeting with Mayor Lisa Brown, and that Brown never responded to his original meeting proposal.

At 5 am every morning, Gavin Cooley meets a group of concerned citizens outside City Hall, ready to lead them through the dangers of downtown Spokane.

He’s somewhere between a college tour guide and safari expedition leader; he’s energetic and knowledgeable of the history of the area feeding his participants nuggets of lore about his experience working with city government as they move through Riverfront Park. But when it comes time for the riskier leg of the tour — braving the viaducts that pass under the elevated railroad tracks in downtown — Cooley confidently takes the lead, speedwalking past the few unhoused people sheltering under the bridges.

Without Cooley’s group, some of the participants say they would never feel safe enough to make the trek. “ I used to be able to go walk around at lunch anywhere downtown. I won’t, and I can’t now,” said Julie Demakis, one of the regular participants in Cooley’s walks. “I have to have my husband with me and he won’t let me go by myself.”

The group only saw about a dozen homeless people this Tuesday, huddled around under the viaduct for warmth or sleeping on the stoops of closed businesses, though sometimes there’s more adrenaline. Usually it’s from a safe distance — last Friday, Cooley’s group saw an assumed drug dealer with a “ giant gallon bag of fentanyl pills,” they said — though once a participant felt ill because they got close to fentanyl smoke, Cooley wrote in an email.

And on this morning, they saw evidence of more danger: an unregulated trash fire under the viaduct and a broken car window outside The Ridpath apartments.

To his credit, Cooley always returns the tour group safely to City Hall, where they circle up and share how they’re processing the experience and how their perspective has changed.

“This is part of action and seeing firsthand, because everyone says, ‘Oh, there’s open drug use, or oh, there’s people buying drugs,’” Derek Baziotis, another frequent walker, said at the end of Tuesday’s walk. “Until you’re out here and you see it, you don’t actually really see what the crisis is.”

Afterwards, Cooley marks their tour with a postcard home: an email blast to the audience following along from their computers. Each email includes a smiling selfie of the group and, sometimes, photos of people in distress, sleeping outside in the cold, sheltering under bridges with their belongings piled next to them, smoking fentanyl.

The experience is eye-opening for Cooley and a lot of the people who join him. “ I didn’t know what I know this week, because we’re seeing new things all the time.”

But for the unhoused people the walkers encounter, they might see something different: a group of warmly dressed people, bundled safely in their winter layers, speed-walking past and looking straight ahead or at the ground while talking in hushed voices about “the homeless,” “the drug addicts” — the “problem.”

And they’re gone, off to finish their loop and head back to their lives.

Reverse engineering success?

But to Cooley, the walk isn’t about sightseeing at all. It’s about exerting pressure.

Cooley works for the Spokane Business Association, a business interest advocacy group formed in 2024 by Larry Stone, one of the city’s largest conservative donors. Cooley served as the CEO for SBA for almost a year, but announced he was moving into a new role as the director of strategic initiatives earlier this week.

The 5 am walks, and the emails Cooley sends out after them, are two primary tactics of Cooley’s main strategic initiative for SBA: completely eliminating visible homelessness downtown.

Cooley had been sending out emails to the SBA listserv of around 2,000 people (and 4,500 readers on LinkedIn) since early January, drawing attention to what he characterized as the city’s failure to treat the opioid epidemic and downtown homelessness as a real emergency, but the walks didn’t start until the middle of February.

The idea for the walks originated in a February 6 email, where Cooley hypothesized about what it would look like to “reverse engineer success,” when it comes to eliminating homelessness.

If the mayor led her cabinet in a forced march through downtown every morning at 4 am “until they could complete that mile without seeing a single person sleeping on the streets or struggling with addiction,” Cooley wrote, “exhausted and desperate” city leaders would finally move with urgency and collaborate both across departments within the city and with other jurisdictions, like the conservative leaders of Spokane County.

A week later, Barry Barfield, administrator of the Spokane Homeless Coalition, pitched his own version of the hypothetical: a milelong “5 am Crusade,” from City Hall to the County Commissioners’ offices with the goal of getting community and elected leaders to see the “worsening crisis of homelessness, drug overdoses and public safety as the REGIONAL CRISIS that it is,” (emphasis Barfield’s).

Cooley quickly joined forces with Barfield, sending the details out to the listserv with the promise that the next day, they’d start at the County Commissioners’ offices and walk a loop that ended at City Hall — aiming to put equal pressure on both the city and the county to pool resources and collaborate on a real solution to visible homelessness downtown.

“We will continue until we see real progress,” Cooley wrote. When his group can walk a mile downtown and not see a single person sleeping on the streets or publicly using drugs, the walks will end. It will mean they’ve succeeded, Cooley told RANGE.

The walks began on February 17 and have continued every morning since.

RANGE and local street photographer Ben Tobin joined Cooley, Barfield and four other people the morning of March 11. The group encountered about a dozen unhoused people, and didn’t see the first person until they were 37 minutes into the hourlong walk.

But Cooley doesn’t take that as a sign that they’re succeeding, because they haven’t gotten any engagement from Mayor Lisa Brown, who faces the vast majority of criticism from Cooley both during the walk, his emails and in a subsequent interview.

Cooley’s position is that unless Brown sets a “zero tolerance policy,” for downtown homelessness, or make the more progressive-values-friendly commitment that “ We will not abandon another person to being on the streets or sidewalks going forward,” nothing will get better.

For people like Julie Demakis, her husband George (who also works for Larry Stone) and Derek Baziotis, who frequently join Cooley and Barfield on the early morning walks, the goal seems to revolve more around wanting the mayor and other politicians to look straight at the crisis and get an understanding of what homelessness and drug use really look like in downtown.

“ Come out at five in the morning, walk it and see for yourself truly how bad it is,” Baziotis said.

‘What are they doing to help?’

It’s no secret that Spokane is in the midst of a two-headed crisis: epidemics of homelessness and opioid abuse. Sometimes the two affect the same person — especially in the population of people who live visibly unsheltered lives downtown — although both city leaders and advocates caution against assuming that solving someone’s addiction will solve their homelessness, or vice versa.

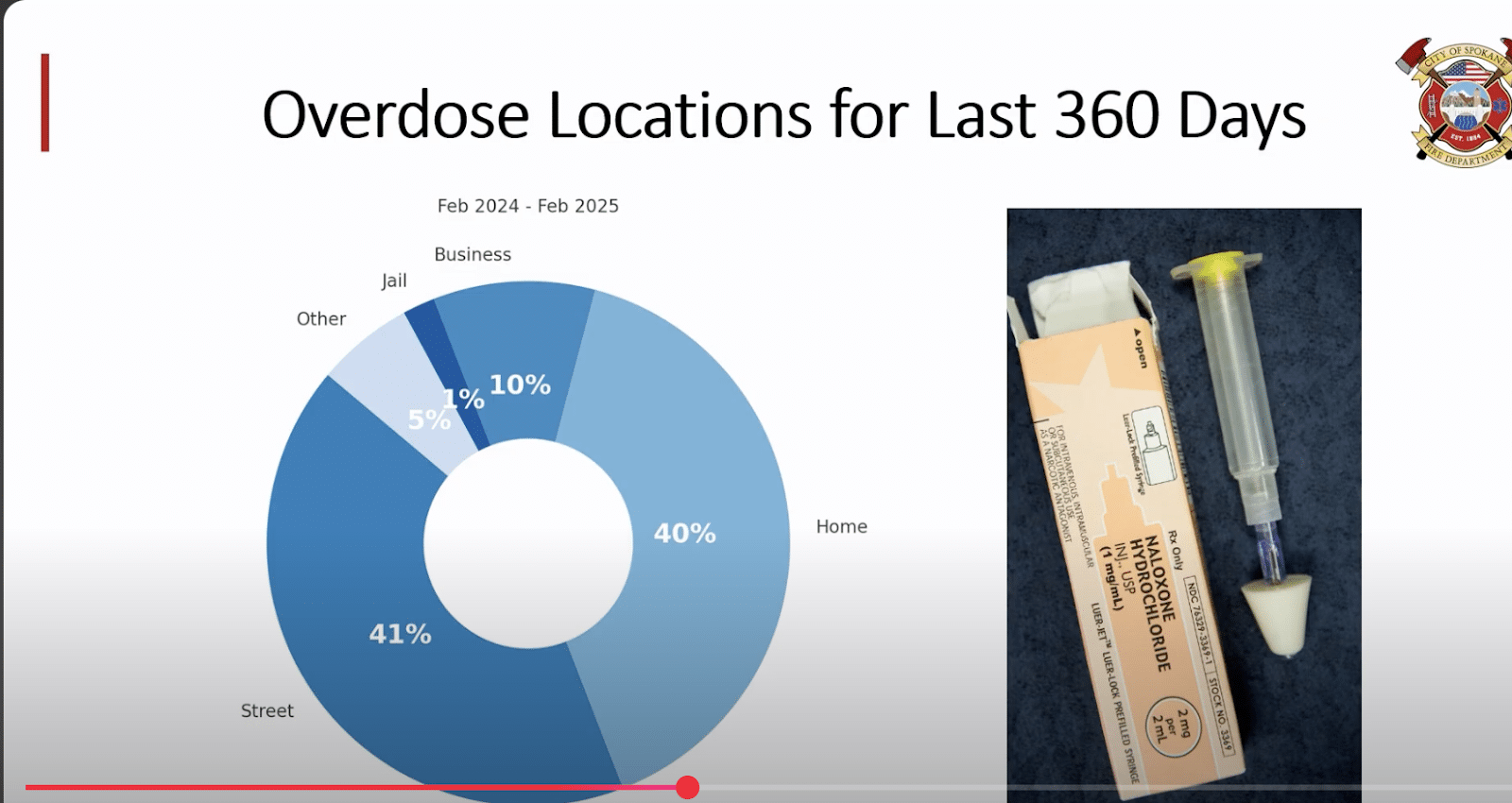

Brown highlighted the individualized needs and circumstances of each unhoused person, and the large amount of “unseen” homelessness, like couch-surfing and sleeping in cars. Council Member Paul Dillon pointed to recent statistics from the Spokane Fire Department showing that during February, overdoses on the street accounted for about 41% of all overdoses in the city. Overdoses within a home were roughly equal: making up about 40% of the total.

Even Cooley agrees, to an extent.

“ You cannot conflate mental health issues and drug addiction with homelessness at all,” he said. “But in terms of downtown, you actually can, and I think we would all agree — and I’ve never had anybody disagree — that probably 100% of the people we’re seeing sleeping on the streets of downtown Spokane have some level of mental health or drug addiction issues.”

Other cities have reported their opioid epidemics are on the wane. Spokane’s is getting worse.

While one of the walkers described the city’s approach to homelessness as “all talk, no action,” — in contrast to the walks, which are a form of action — progressive politicians feel it’s the opposite.

“What are they really doing about [the crisis] besides just go, gawk at people and take pictures?” Council Member Lili Navarrete said at a council committee meeting on Monday, March 10. “What are they doing to help? Are they all getting together and putting money together? Are they putting their money where their mouth is?”

Council President Betsy Wilkerson’s impression of Cooley’s group was that they just “walk to look.”

“On the walk that you went on, Nicolette, was any help offered?” she asked the council’s Manager of Housing and Homelessness Initiatives Nicolette Ocheltree, who went on the walks for five days in a row. “Were there any pamphlets of ‘here’s a list of services, call these numbers?”

Dillon took issue with the emails Cooley sent each morning, which sometimes included pictures of unhoused peoples’ faces. “ Is there ever like a conversation around the ethics of taking photos of people without their consent?” he asked Ocheltree.

Mayor Lisa Brown gave similar criticisms in her interview with RANGE: Cooley’s walk isn’t helping make anything better, it’s reinforcing a negative “self-fulfilling prophecy,” about downtown — and the story he’s telling is biased against her and the city, she said.

“He has a very specific employer with a very specific agenda,” Brown said. “At this point, I don’t think he’s telling a neutral or objective story, he’s leaving a lot of pieces out of it because if he were to give credit in an unbiased way, it might not reflect the agenda of his employer.”

Ocheltree herself expressed complicated feelings about the walks. She learned things, she said: the parks and bridges have gotten a lot cleaner, but open drug use in the viaducts was worse than she expected.

Ocheltree said one major positive was seeing a moment of empathy from one of the other walkers — “One woman said, ‘if my toes are cold, her toes are cold, if my hands are cold, her hands are cold,’” — but there were also things she felt really uncomfortable with.

As someone who had been homeless before in her life, Ocheltree said the photography without consent was “a real pain point” for her. “ These people who are experiencing homelessness on the streets, it’s not as though they’re animals in a zoo,” she said. That wasn’t the only issue she had.

“There was one gentleman who seemed like he wanted to see somebody suffering,” Ocheltree said. She described another person as “unnecessarily aggressive,” towards an unhoused person they saw.

The day after she presented to council, Ocheltree joined the walk for a sixth time, the same day as RANGE. On that morning, she brought meat and cheese snack packs to hand out to the people they encountered. Despite seeing only about a dozen people, all her snacks were gone by the end of the walk, as was her half-drank Perrier, which she offered to a man who was thirsty, and which he gladly accepted.

Ocheltree, the city employee, was the only person who engaged with the people they passed as they walked.

The walks have been characterized as voyeuristic by critics, including council members. When Cooley hears his project characterized that way, it invokes an emotional response. While he’s on the walks, Cooley said he’s thinking about one of his children, who has struggled with PTSD and addiction issues.

“I used to have nightmares thinking I’m going to see my child in one of these settings,” Cooley said. “I’m afraid of seeing their face. There’s no voyeurism in the walk.”

But he also wrestled with some of the inherent contradictions wrapped up in the concept of the walks.

“ I try not to look at people’s faces when I’m walking by. I feel like it’s a little, almost condescending to say good morning. And I always do when I walk by the people but, it doesn’t feel like a good morning to these folks,” Cooley said. “And I don’t know how you strike a nonvoyeuristic attitude on a walk like that when you’re walking around with a group of people at 5 am. I, frankly, try to move through as quickly as possible and not really linger.”

He added that “everyone has their own reasons for being there,” but emphasized that ultimately, “no, I don’t think there’s anything voyeuristic about it at all because I go home greatly saddened.”

Conservative council members also took issue with any comparison to voyeurism. Council Member Jonathan Bingle, who went on the first of the crisis walks, said, “ It wasn’t just people there to gawk and make fun of, or ridicule or whatever and so, I don’t like that being said about the group either.”

Whether or not the walks are voyeurism, they certainly aren’t service- or outreach-oriented.

The morning we joined, Ocheltree handed out two dozen snack packs she bought with her own money. In stark contrast, was an email Cooley sent out a month earlier, where he profusely thanked local business David’s Pizza, who had donated breakfast pizza to the walking group.

None of that pizza was shared with the unhoused people the group encountered that morning.

On the question of the ethics of photographing someone sleeping on the streets, Council Member Michael Cathcart appealed to the legality of the practice, saying photos taken without consent in public are perfectly legal, because there is no expectation of privacy on the streets. He compared it to photos snapped by automated cameras when people break the law and run red lights.

Still, this week, Cooley took the criticism about the photography to heart.

After hearing condemnation from both council members and from his own sister, who is a service provider, he resolved to no longer send out pictures that include the faces of people on the streets but still “capture the devastation and suffering to some degree.”

‘Zero tolerance policy,’

But Mayor Lisa Brown says she doesn’t need photos or a 5 am walk to know how bad things are — it was one of the defining issues of her campaign and now, she estimates she spends 25% to a third of her time working on housing and homelessness issues.

Brown points to the seven scatter site shelters her administration has opened, with two more on the way, also moving the city away from a congregate shelter model to a navigation center model that’s statistically more effective. She says she makes a point to get firsthand knowledge of the crisis happening in her city by walking or biking most places she goes downtown, at all hours, noting what she sees.

She participated in the Point-in-Time count this winter — joining volunteers scouring the streets to talk to unhoused people — and joined Barfield on what he calls an “urban plunge,” a guided trip to homeless encampments where she spoke with people living on the streets. (“We just didn’t feel the need to post pictures about it,” city spokesperson Erin Hut added.)

Brown says she has mobilized her state connections to maximize the amount of dollars flowing into the city for housing and homelessness issues. She’s activated 1590 funds — which come from a sales tax within the city and previously sat untouched — to pay for inclement weather sheltering and affordable housing developments, and gotten creative with the city’s budget deficit and aggressive with ongoing contracts, taking back millions in unused funds and successfully getting the city out of its blackhole lease with the Trent Shelter, a building owned by Cooley’s boss, Larry Stone.

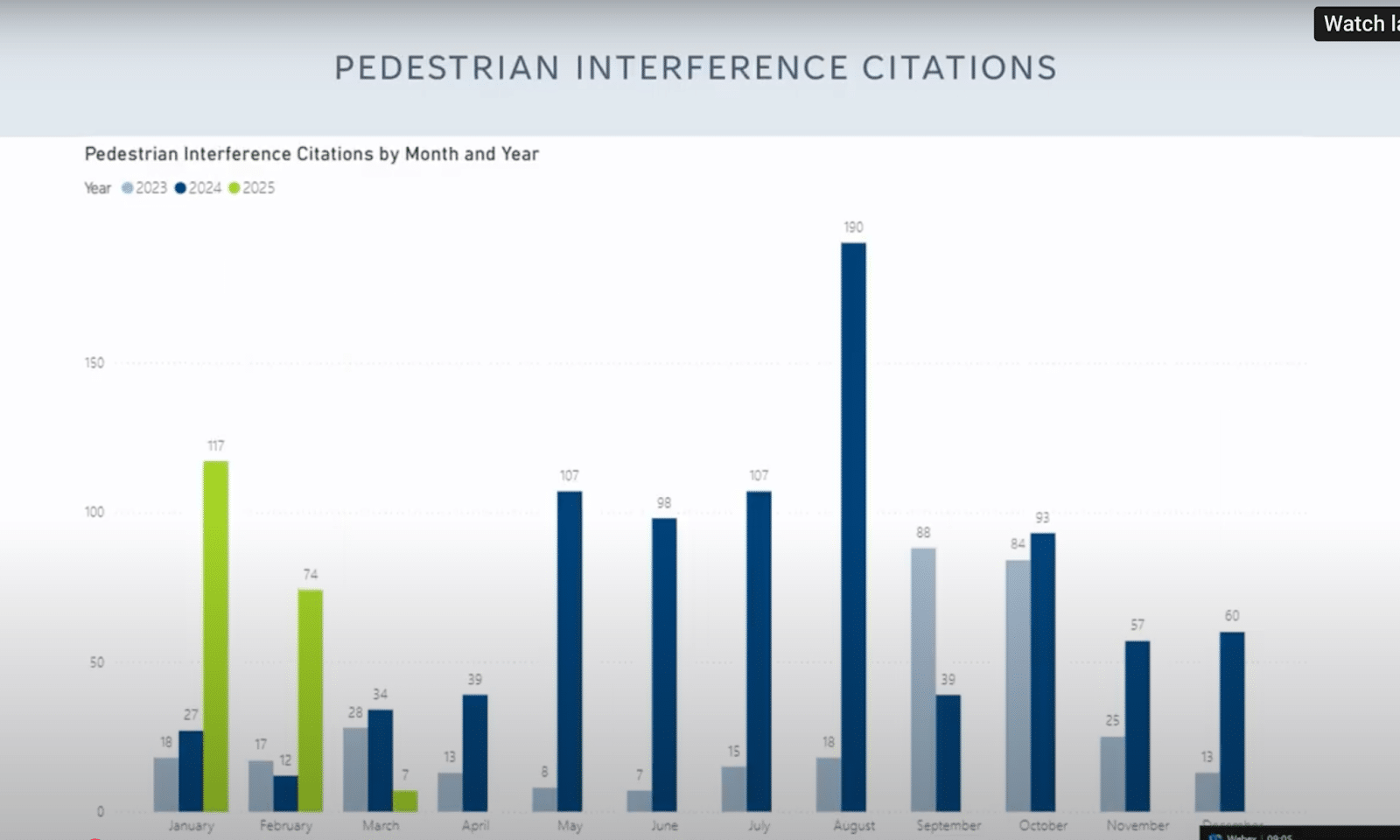

Some of her tactics are more conservative. Under Brown, enforcement of laws on the books that are intrinsically tied to homelessness, like unlawful camping and pedestrian inference, has spiked. Her administration is also using city dollars to increase opioid prosecution capacity — filling a gap left by Trump’s federal funding freezes. Overall crime is down, enforcement of crime is up.

On the housing supply side, Brown points to her work with council to roll back development restrictions in city code and increase density limits downtown.

None of that is enough for Cooley and SBA. “She could open 50 more scattersite shelters and it wouldn’t be enough,” Cooley said. He thinks that expanding shelter capacity might actually worsen the problem, doubling the amount of unhoused people downtown, because the approach wouldn’t have started with a “zero tolerance policy.”

If Brown doesn’t start with the goal of “zero tolerance” for visible unhoused people in downtown and work backwards from that, Cooley said, whatever she does won’t work.

“She’ll never find a way to quite say ‘no’. She’ll always see someone on the street and think, ‘how can we help this person?’” Cooley said.

Without that zero tolerance policy and a largescale collaboration with the county, specifically with County Commissioner Al French, she’s doomed to fail, Cooley thinks.

That’s the twofold goal of Cooley’s walks: get Brown to agree that any number of visibly homeless people downtown is too many, and get her to sit down with French and coordinate the city and the county’s responses to the emergency.

‘This Isn’t About Politics — It’s About Saving Lives and Fixing What’s Broken’

None of this is political, Cooley writes repeatedly in his emails. One of his subject lines: “This Isn’t About Politics — It’s About Saving Lives and Fixing What’s Broken.”

Brown thinks that’s laughable.

“[Cooley] has an employer with a very specific agenda and they’ve made it very clear that if the city’s not doing what they want, they’re going to apply tactics of pressure to try to bring that about,” she said.

It wouldn’t be the first time Cooley and SBA tried to bully Brown into bending to their will, she added. Last year, when Brown ran a public safety sales tax on the ballot, SBA initially endorsed the tax, encouraging members to vote in favor of the tax to increase public safety downtown. But behind closed doors, the conversation was different.

“[Cooley] came to me after the SBA said they would support the community safety initiative and said they would withdraw that support if I didn’t change where we were planning to allocate those resources, that we shouldn’t be spending money on fire and fire capital and neighborhood resource officers,” Brown said. “T hey wanted me to publicly announce I was going to change the allocation of those resources.”

Cooley described it more as “a running conversation,” but admitted to expressing a lot of frustration with Brown’s plan for how to allocate the funding.

“Pulling our support was definitely on the table,” Cooley wrote in a text to RANGE. “We felt, and still do feel, that the promises made were not held up. In particular, much of the funding went to fire department capital purchases that would not have any impact for many years.”

It’s not just their history that makes Brown leery of Cooley’s assertion that his efforts aren’t political — it’s his ongoing email rhetoric.

“ When they say it’s not politics, but then they always focus on the mayor, I’m sorry, but that feels political to me,” Brown said. “Especially given what they did during the campaign, which is to spend a million dollars to try to make sure I wasn’t elected.” (In easily the most expensive mayor’s race in Spokane history, then-Mayor Nadine Woodward and her supporters – largely realtors and developers, including Stone – almost doubled up on Brown and her supporters, outspending them by just under $670,000.)

The county, the city, collaboration, control

While the initial premise was to encourage collaboration between the two entities by alternating walk destinations between Spokane City Hall and the County Commissioners’ offices, since the first week, every walk has left from and ended at City Hall.

Cooley’s emails have gotten more and more targeted at Brown and the city of Spokane. We read every single email Cooley sent to his listserv from January 1 to March 13. Cooley referenced Brown and the city positively six times and the actions of the county positively 13 times (14 if you count a photo of Cooley and his group smiling in front of a County sheriff’s car). He referenced Brown and the city negatively 23 times, and the county negatively once.

In one email, the subject line read: “A Tale of Two Spokanes: Beauty, Desperation, and the Barriers to Meaningful Change,” painting a picture of recent county actions as positive and city action as supporting “policies and decisions that prioritize political identity over real solutions.”

He frequently criticized Brown’s leadership, comparing her unfavorably to past male leaders of Spokane like Mayor Jim West and David Condon, and to Houston Mayor Annise Parker, who is frequently lauded for her handling of her city’s homelessness crisis. “True leadership means confronting the problem head-on, not avoiding it,” Cooley wrote in one email.

Cooley also alleged that Brown wasn’t enforcing anti-camping laws, though data shows otherwise, with citation records presented this month by Police Chief Kevin Hall showing massive jumps in enforcement under Brown’s tenure — influenced in part, he said, by the 2024 Supreme Court ruling on the Grant’s Pass case.

In another email, Cooley blamed Brown for the lack of collaboration between the city and the county.

“When a key member of our city’s political majority refuses to engage directly with key members of the county’s political majority, it tears apart that tapestry, leaving the different parts of the system unable to properly interact and solve the problems before us,” Cooley wrote. “A crisis response requires cooperation, not political entrenchment or personality-driven obstruction.”

On the walk RANGE attended, Cooley told a story about a “competition” between County Commissioners Al French and Josh Kerns, where they tried repeatedly to get Brown to meet with them. Whoever got a meeting scheduled with her first would win, Cooley said.

“They both lost,” George Demakis, one of the walkers, chimed in.

Brown said that was unequivocally false. Her office has received one phone call from Kerns asking to set up an off-campus meeting between her, Kerns and French, but without staff. She said she proposed an alternate meeting where staff would be present to ensure whatever came out of the conversations were “accurately portrayed.”

From French, there’s been radio silence, and spokesperson Hut said Brown’s office had sent French “ a slew of messages trying to engage on a variety of topics that have been unanswered.”

Kerns told RANGE that there was never any competition (“and if there was, I certainly would have lost because I only called the one time,”). He also said that Brown never proposed an alternate meeting with staff.

“She never called back,” Kerns said. “For her to say we’re avoiding her is strange.”

(RANGE is waiting on public records requests submitted at both the city and the county to confirm what communications between the commissioners and Brown have been.)

Brown contends that French and Kerns are avoiding her, but she meets with Mary Kuney, Republican Chair of the County Commission, monthly to discuss ways the city and county can work together. Brown says those meetings have resulted in a number of regional collaborations she considers successful, like the opioid overdose dashboard in partnership with the Spokane Regional Health District (a tool that was created after RANGE’s reporting on the lack of accessible, up-to-date data) and joint federal funding requests for things like opioid prosecution and additional beds at the county’s Crisis Stabilization Center.

Just today, Brown and Wilkerson announced a joint proposal with the county to invest $1.5 million in behavioral health services and treatment programs in our region.

None of that is good enough for Cooley. “Our current fragmented efforts — masquerading as a regional approach — are not working,” he wrote in his most recent email on March 13.

The white whale

Cooley says you could consider his focus on a collaborative, regional approach his “white whale” — referencing Moby Dick, the whale who (spoiler alert) kills the man pursuing him at the end of Herman Melville’s classic novel.

He says it’s the reason he flipped from longtime Democratic donor and member of Brown’s transition team to public face for a conservative business association. It’s the reason his emails largely criticize Brown, rather than the county. It’s the reason he’s cancelled vacations with his wife so he can be at City Hall for the walk at 5 am every morning.

If every municipal government and every service provider could get in one room and on the same page, coordinating all their money and resources to jointly address issues of homelessness in the region, Cooley is sure they could solve it.

At the end of Woodward’s term, along with two other former City Hall administrators, Theresa Sanders and Rick Romero, Cooley had shepherded a proposal that had the tentative backing and support of eight local governments: the county, the city, Spokane Valley, Liberty Lake, Millwood, Airway Heights, Cheney and Medical Lake.

When Brown stepped into the mayorship, Cooley was really optimistic the region was finally on the cusp of that crucial collaboration. With her experience working across the aisle in state government, Cooley says he thought she would be the leader who could finally figure out a way to work with the county to coordinate their respective pools of money, resources and expertise. As of now, the county receives more funding for mental health resources and controls the Spokane Regional Health District, which runs one of the state’s largest publicly administered opioid treatment programs. Meanwhile the city receives more funds for shelter and affordable housing.

Cooley met with Brown monthly, and thought she was an ally in the effort to form a regional homelessness authority, until she wasn’t anymore.

Brown ultimately pulled her support for the regional efforts, citing concerns with the proposed governance and financial structure of the authority, which would have left the city funding a large chunk of the authority’s activities, while holding only two seats on the 14 person board.

For Cooley, it was a betrayal — the mayor he’d backed with $150 of his own money “unilaterally” killed the proposal he’d pinned all his hopes on, after promising her support.

But to Brown, it was a smart business move. She inherited a city with a budget deficit, and wanted to shore that up before handing the reins of any city funding over to a brand new organization.

Trusting a brand new and untested regional entity looked risky to her, too. The progressive city and the conservative county have historically struggled to work together or agree on equitable distribution of resources, a relationship that has only gotten more tense now that Spokane has a Democrat mayor (see the county’s refusal to give Brown a say in the city’s representation on the SRHD board, the city’s break up with Spokane Regional Emergency Communications over equitable funding concerns, constant city versus county tensions on the Spokane Transit Authority board and the recent end of the city and county’s collaborative Behavioral Health Unit.)

“She’s right. The county should be criticized just as much as her,” Cooley admitted. But in his mind, Brown singlehandedly sank the regional homeless authority, so she bears the majority of the responsibility for what he would qualify as real collaboration.

Despite Cooley’s assertion that Brown was the sole killer of the regional homeless authority, the efforts had actually fizzled and ground nearly to a halt before Brown even won her election.

First, service providers balked at the plan’s inclusion of incarceration as a housing plan.

Then, there were more sparks when providers found out that Theresa Sanders, one of the three architects of the regional homeless authority, had close ties to Stone — the conservative donor, owner of the now-closed Trent Shelter and creator of the anti-homeless, fear-mongering video “Curing Spokane.”

Maurice Smith, a longtime homeless advocate, told The Spokesman, “We all know we need a regional authority to consolidate things, and we were all so desperate for it that we took it at face value without realizing we were being handed a Trojan horse.”

A few weeks later, and more than two months before the election that brought Brown to office, the Spokane City Council voted to pump the brakes on the regional approach, asking for more data, more transparency and less reliance on jail.

Cooley hoped Brown would revive the regional efforts. Instead, she put the final nail in its coffin.

‘Harsh realities’

Life has a way of coming full circle: accusations of Larry Stone’s influence and an overreliance on jail were a large part of what sank the regional collaborative plan.

Now, Cooley works for Stone at SBA — which has a stated goal of building a new jail — and sends emails advocating for involuntary commitment of unhoused people to Geiger Corrections Center.

“Prioritizing the civil rights of individuals who are incapable of caring for themselves over the preservation of their lives — and over the health and safety of our communities — is neither moral nor compassionate,” Cooley wrote in an email on January 30.

“ There comes a point at which we all forfeit our freedoms based on our behaviors,” Cooley told RANGE, in defense of the email. “If I don’t show up to work for a week, I’m gonna forfeit my right to a job here. That’s just the harsh realities of life.”

(Since he sent the email, though, he has shifted his stance a little. Instead of pushing for the city to illegally detain homeless people, he is planning to refocus his advocacy at the state level, asking them to change laws to make it easier for cities to invoke Washington’s Involuntary Treatment Act, also known as Ricky’s Law.)

For Brown, there are neither simple silver bullets for collaboration, nor white-whale solutions just over the horizon. She says there’s only steady, careful, data-driven work: opening more scattersite shelters, increasing affordable housing options by changing zoning and leveraging 1590 funds to incentivize development, and approaching people in need with individualized solutions that have a higher success rate than things like involuntary commitment — which has a higher rate of recidivism.

Would it be easier if the city and the county worked together better? Sure, Brown said.

“Commissioner French can call me anytime he’d like and we can meet,” Brown says. “A five am walk just feels more performative than what I’m looking for.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to reflect information from County Commissioner Josh Kerns.